This sense of liberation is mirrored in his sources of inspiration, which increasingly derive not from other artists but from cartoons and science fiction, of which he has always been a huge fan. The irreverent animated sci-fi series Rick and Morty is a particular favorite. “In Rick and Morty, what is a wrong body? There’s no such thing. If you want to have 500 legs you will have 500 legs,” he said.

Ghenie has applied this same freedom to his portraits of Marilyn Monroe. Coincidentally, these works came about through another mini epiphany. Having watched The Andy Warhol Diaries on Netflix, the artist happened to visit Christie’s website since he had a work on sale with the auction house. (That work was 2014’s Pie Fight Interior 12, which in May set his auction record of $10.3 million.) On the house’s website, he encountered an installation photograph of Warhol’s Shot Sage Blue Marilyn and was transfixed, despite never having had any interest in the Pop artist previously.

“Suddenly I had this Marilyn-Warhol explosion into my life,” he said. He was shocked by the almost religious power of the image: “It is glowing. It’s almost like it’s a small miracle and you just want to look at it.”

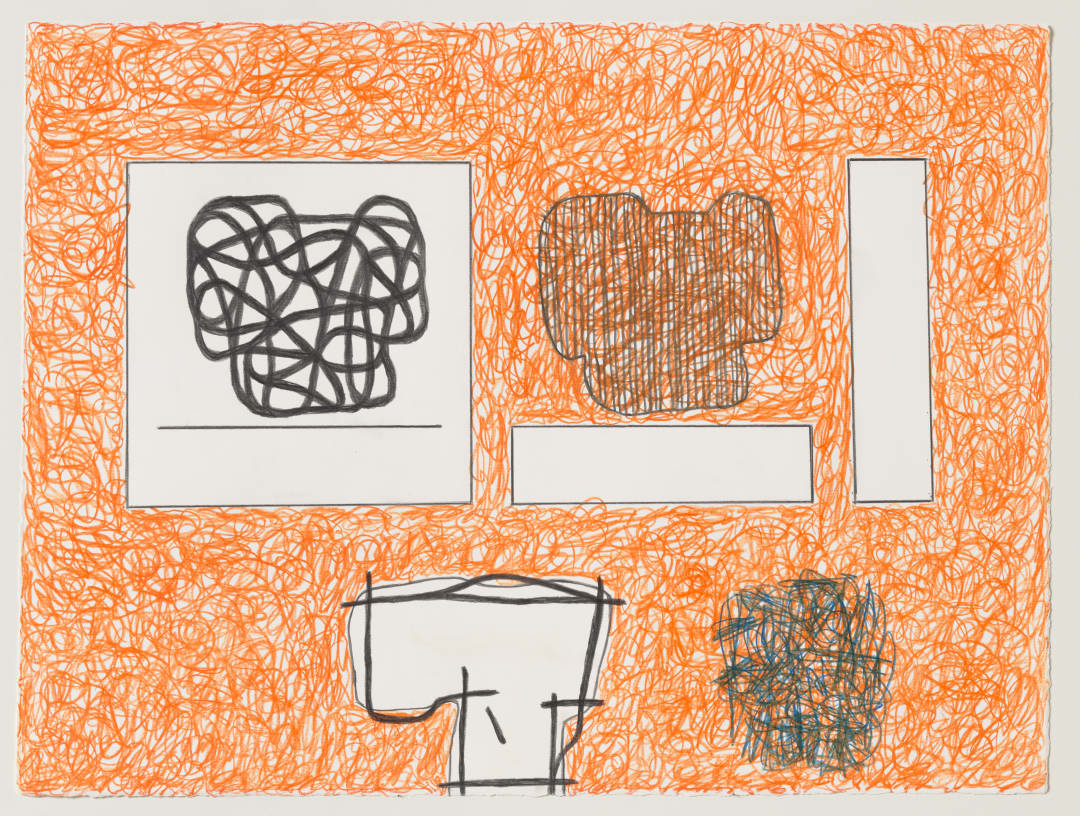

Ghenie felt compelled to incorporate Warhol’s Marilyn into his practice. Retaining only the actress’s blond hair, lips, and one eye in place, he deconstructed Warhol’s smooth image, giving the star the Rick and Morty treatment, so that the end result is almost an alien version with misplaced features and tubular organic forms growing from her head. The portraits somehow evoke Monroe’s vulnerability and even ugliness behind the celebrity mask, although Ghenie’s fascination is not with Monroe the person but her image and the way she has been kept alive online.

For someone with a phobia of modern technology, Ghenie thrillingly juxtaposes traditional materials such as paint on canvas with uber contemporary references to the latest devices, tapping into the essence of our digitized existence today.