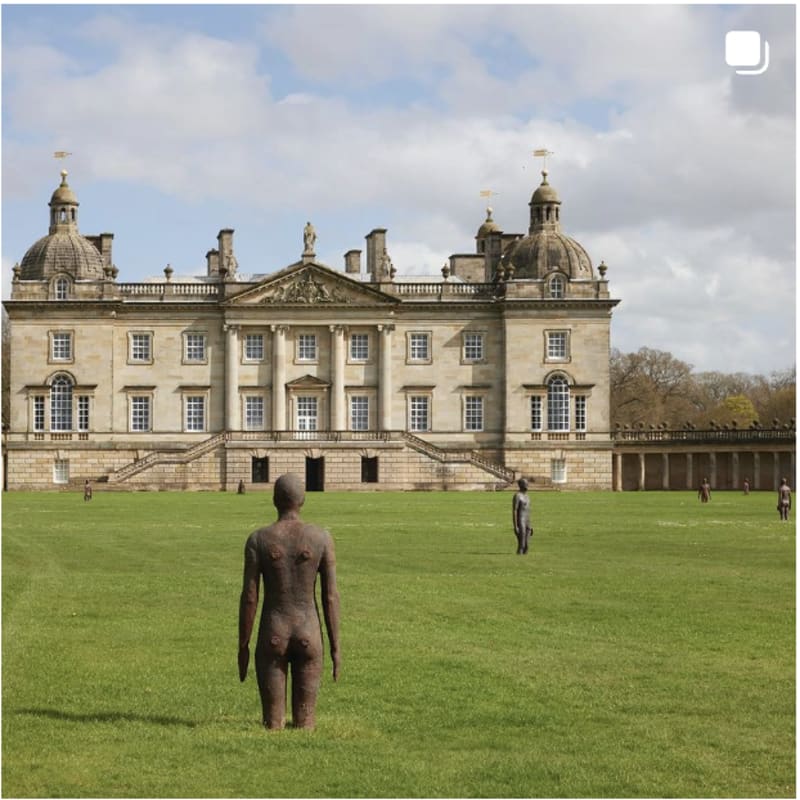

Even so, he tells me he’s aware that “in Britain, the jury is still out” on Antony Gormley. As one of the most popular artists in the UK and beyond, he’s surely referring not to the public, but to the side-eye he sometimes attracts from art critics at home. Gormley happily admits that he is “absolute anathema” to prevailing trends in the art world. The Guardian’s review of his major 2019 exhibition at the Royal Academy made sure to point out that he is a “white, male, Cambridge-educated son of a pharmaceuticals magnate”, and questioned whether casting figures from his own naked body and “leaving representations of this privileged white guy around a world dominated by privileged white guys” gives him the right to tell us anything universal.

Yet the artist thinks he has always been something of an outsider – “slightly odd”, “a late developer” – and his own form, he insists, is “not special… It’s just the body I live within”.

Gormley, in a utilitarian white T-shirt and grey jumper, is a softly spoken, academic presence. His mother was German, and he confesses that “there’s a German ponderous kind of interrogation of everything” that has been passed down through his maternal line. (Post-Brexit, he has applied for a German passport, although it hasn’t arrived yet.) His speech is considered and precise: “I am a temporary inhabitant of an amalgam of cells,” he says, when I ask him if death – a consistent theme in his work – is something he thinks about a lot. “When the time comes, this stuff will have to be put back into the general circulation of transformative material.”

He’s less sanguine about humanity in general. “I don’t think we’re going to be here for very much longer. The planet will continue.” He sees no signs that we are going to take the steps necessary to prevent catastrophic climate-change. “I think we are going to see real suffering. We had [former prime minister Liz] Truss going on about growth at all costs, but it’s just completely mad – we are not going to emigrate to other planets.”

I wonder what he makes of Just Stop Oil’s attacks on great artworks, the glories of Western civilisation. “I wish that they would throw their baked beans at the head of Exxon Mobil, rather than artworks,” he says – yet he insists, if we don’t make the transition to non-fossil-fuel production, that “it’s going to be very ugly indeed, and actually, throwing baked beans at Van Gogh’s Sunflowers seems a fair sacrifice”.

For his own part, he refuses to let his work be transported by plane, while “all of the work is made from recovered materials – we use brake shoes for the iron. It’s smelted with renewable electricity”.

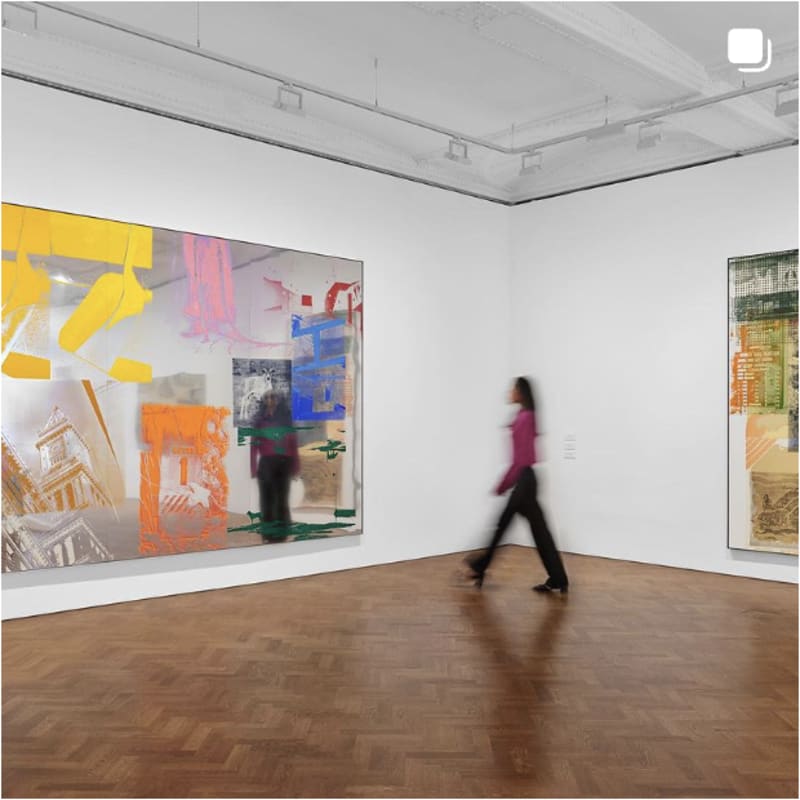

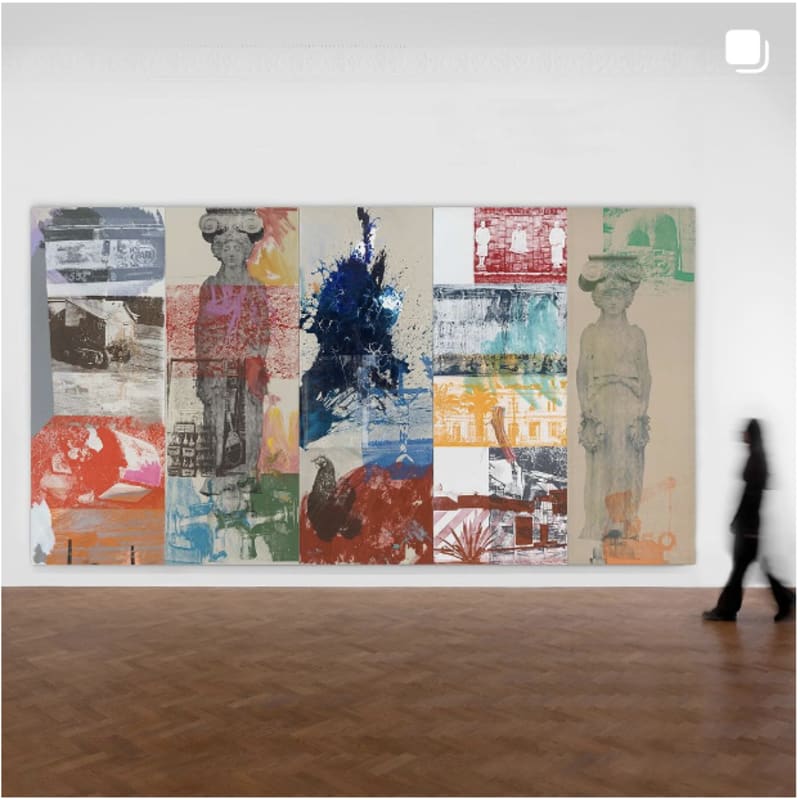

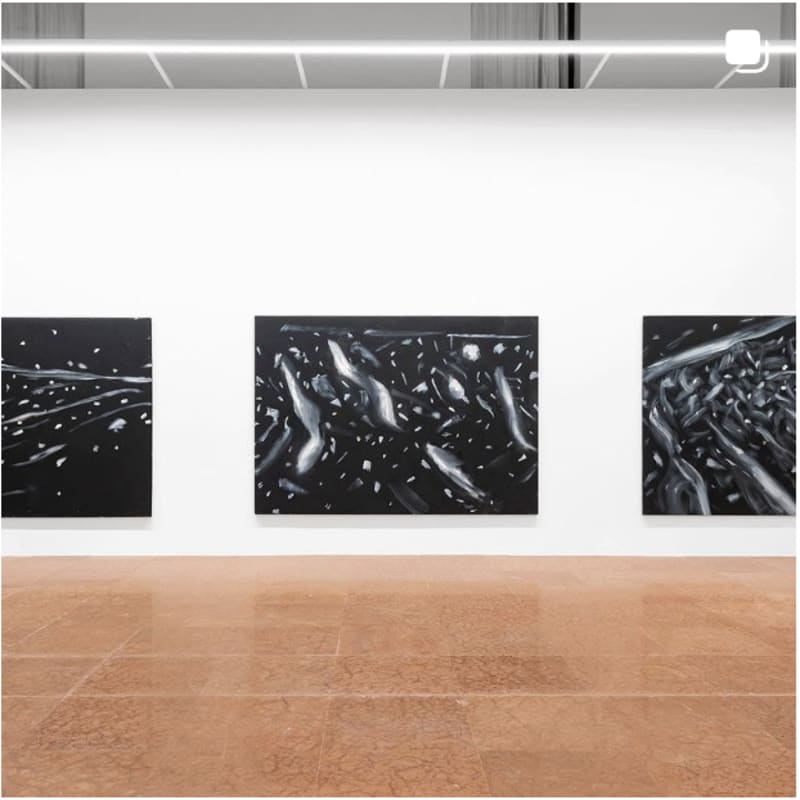

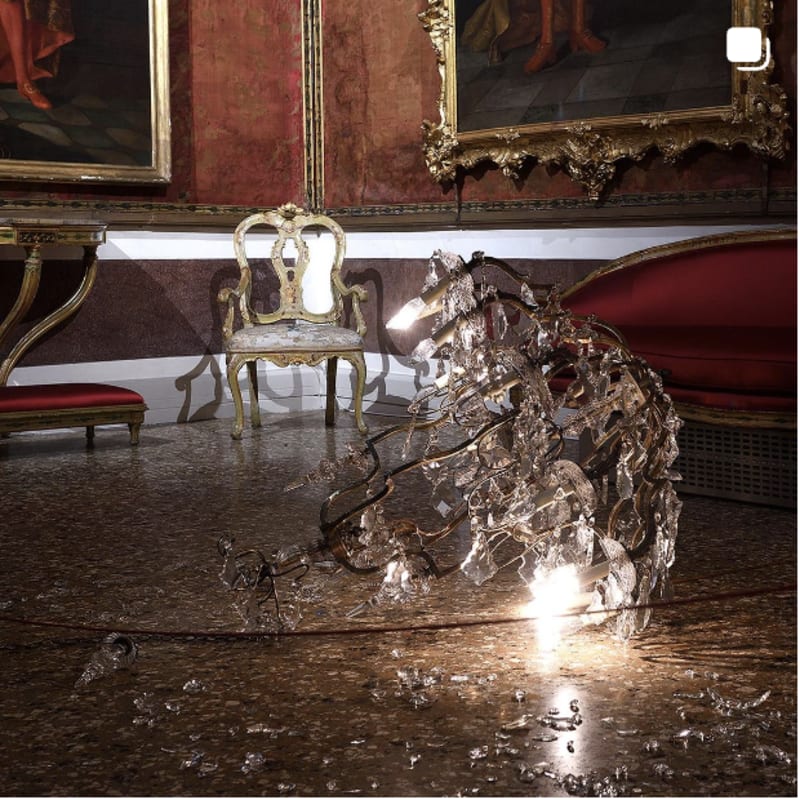

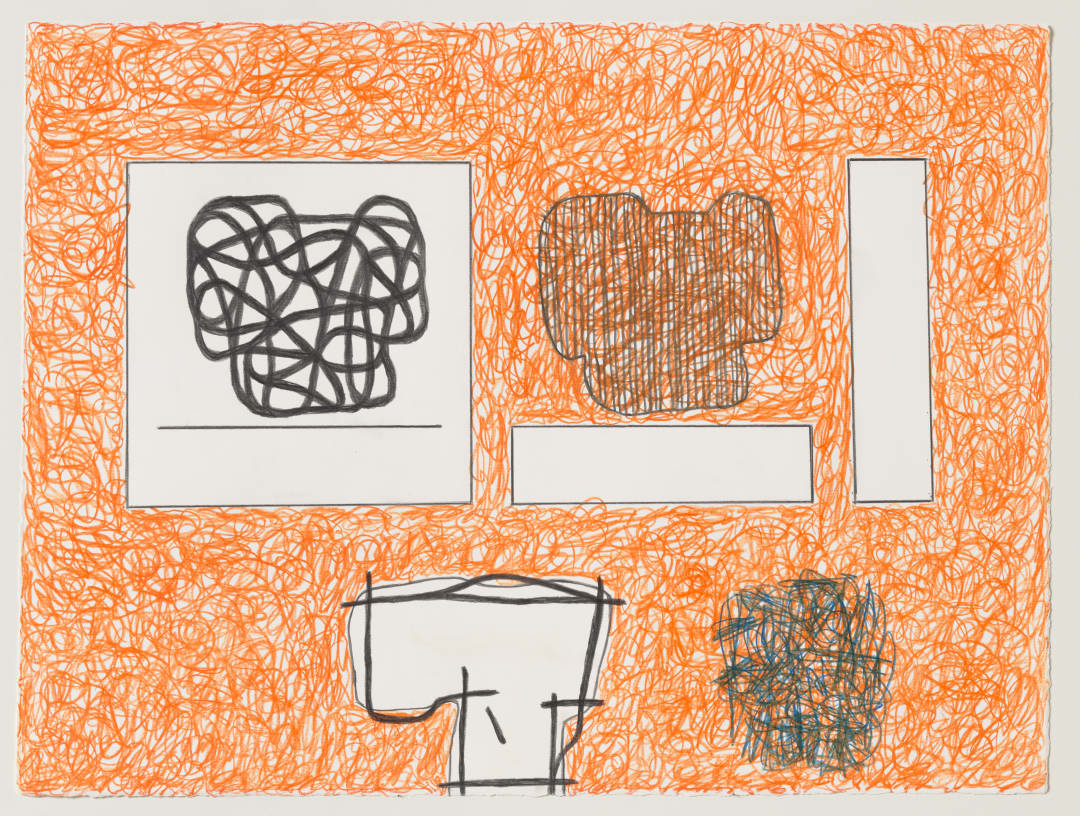

Gormley’s worldview is dystopian. He thinks we’re mentally trapped in a vast grid and “brainwashed by our own systems”; he talks of “the way in which our children are now mentally tortured by Instagram and Facebook and Snapchat”. We’re meeting to chat about a small exhibition he has curated, “A Conversation Through Drawing” between his own works and those of the late German artist Joseph Beuys, at Thaddaeus Ropac’s Dover Street gallery. The boundary-pushing Beuys had been a Luftwaffe rear-gunner, who survived when his Stuka bomber crashed in Crimea. Ropac notes later that “Beuys felt that politics is the only way to change society, and that artists have not enough power” – he became a founding member of the German Green Party. Beuys has been a lasting influence on Gormley, not least on what he describes as his belief that “art doesn’t need the validation of either the market or the aesthetic police of institutional mind control”.

“You’ve got to see what art does as a first-hand experience with people that haven’t paid for a ticket, or don’t feel that they are the cultural elite. That’s been really important to me – put the work in the street, on the mountain, on the beach, and see what happens.” Beuys’s work, he says, helped him step outside the fact that “post-war art was dominated by American sensibilities” through abstract expressionism, pop art, minimalism and conceptualism.

Much of Gormley’s own work stands defiantly outside the pseudo-art movement of today that one might call “curatorism”. “I am a bit concerned about the rise of the curator artist that, in a way, uses other people’s work to illustrate certain thematic issues,” he says.

That’s not to say that, politically, Gormley finds himself entirely at odds with the currents of the day. “There’s no question that the colonisers have to look at the cultures that were colonised and often totally destroyed or devalued as a process of colonisation,” he says. “I grew up with a kind of model of progress in art – from Giotto to Cézanne – and we’ve got to chuck that out. We’ve got to recognise that Occidental art history is one of many interconnected and incredibly complex [threads] of human creativity.”

A former trustee of the British Museum, he has thoughts about the restitution of artworks to the countries from which they were taken. “It’s a very thorny problem,” he says. “I think it’s clear that the Abyssinian campaign and the abstraction of the Benin bronzes, this is war loot, and there is a very cogent argument for its immediate return.”

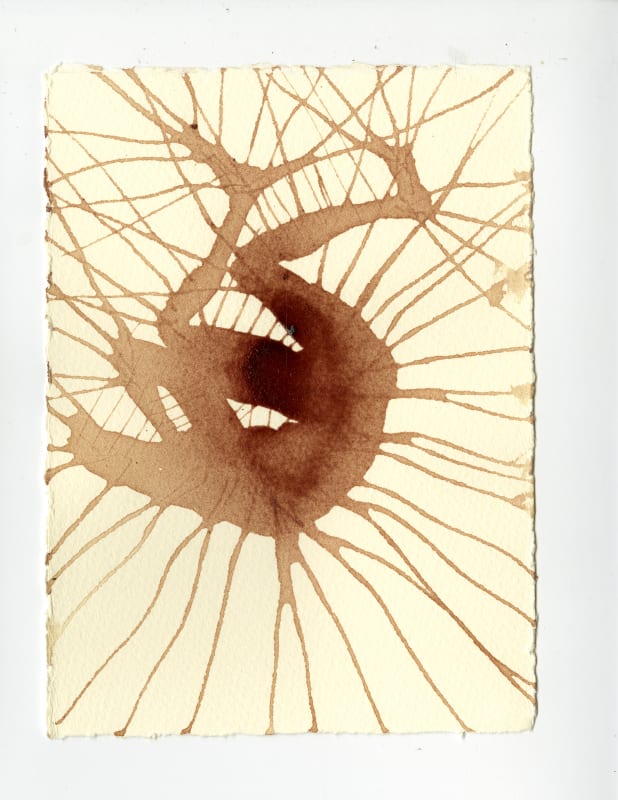

Yet he thinks that “the blank announcement” made by French president Emmanuel Macron in Burkina Faso in 2017, about his determination to return African artefacts held in France, is dependent on several issues: “Who will it be returned to? What institutions will receive it? And will the context it finds be superior to, or doing a different but necessary job to the one that it’s doing in, Paris or London or the Met [in New York]? Museums like the British Museum, with its extraordinary conservation department, in times of really serious instability are necessary places of regeneration.” As a thinker, Gormley often finds himself drawn into serious cultural issues, yet as an artist, he says: “Play is the basis of everything that gets made [in his studio], the kind of playful experimentation with possibility.” Drawing is one of the keys to that process, he notes, as well as his touching point with Beuys: “He and I both needed to draw every day in order to keep in touch with what’s bubbling around in the mud of our subconsciousness.”

Yet he balks at how galleries seem no longer to be prepared to leave interpretation to a visitor’s own consciousness. “I feel that in a time of attention deficit, where we’re all ruled by smartphones, we are in danger of being told what to think. Art is no longer the province of the rich and powerful, by which they continue their dominance – it has to be a conversation in which the viewer does at least half of the work.

“And that discovery of meaning cannot be told by a higher authority – it has to be discovered by the viewer. ‘What is this thing doing in my world? What has it got to do with me?’ Well, it’s up to you to work that out.”