There's an inherent optimism in these works. In these uncertain times, I wanted to create paintings that were joyful, playful and about coming together.

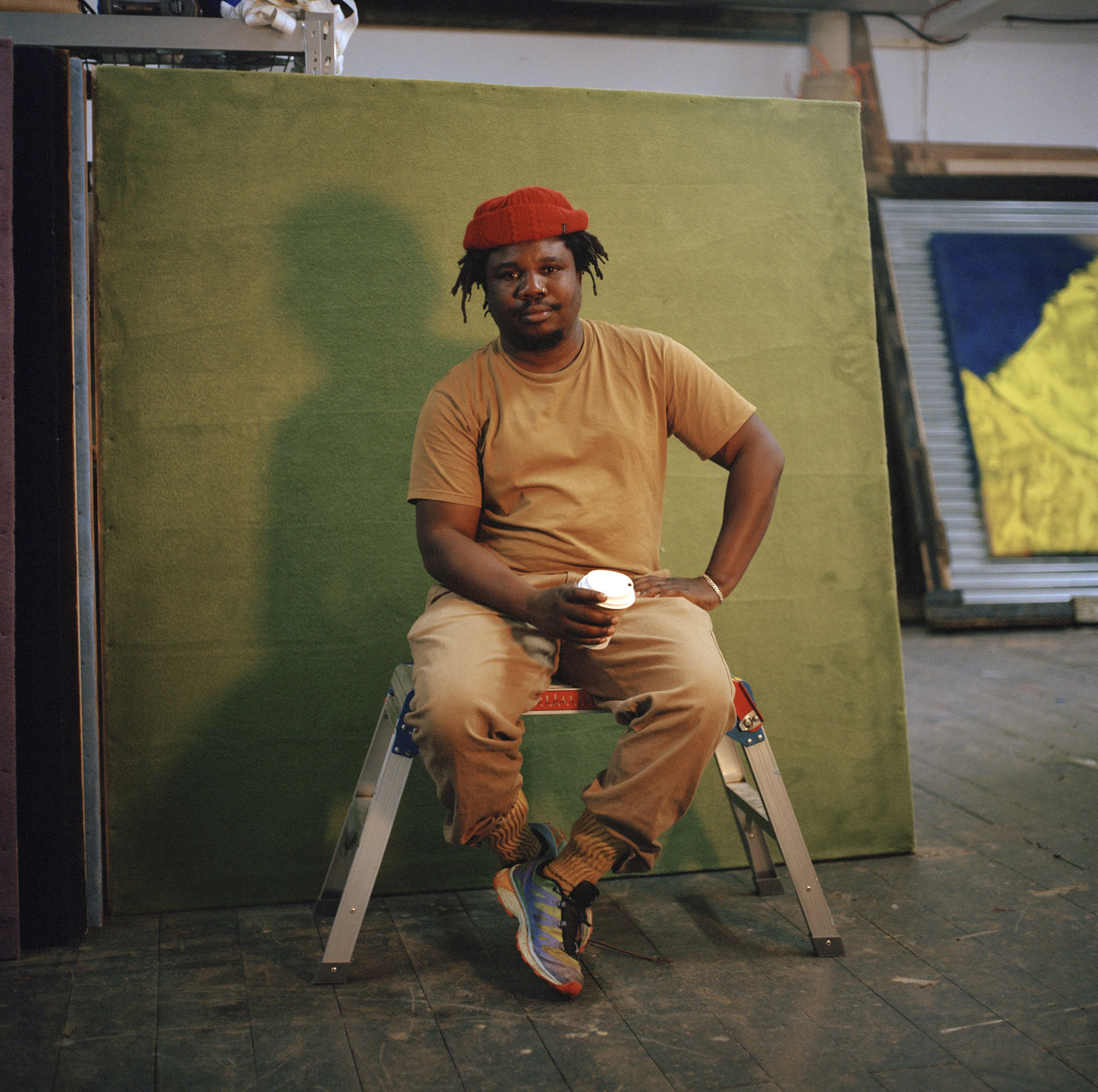

Alvaro Barrington

On the Road (TMS) A9, 2024-26

Oil, acrylic, flash, enamel on burlap / silk screen printed burlap, cotton linen, waxed cotton thread

259 × 190 cm (101.97 × 74.8 in)

Alvaro Barrington

Grace, 2024

Exhibition View

Tate Britain, London

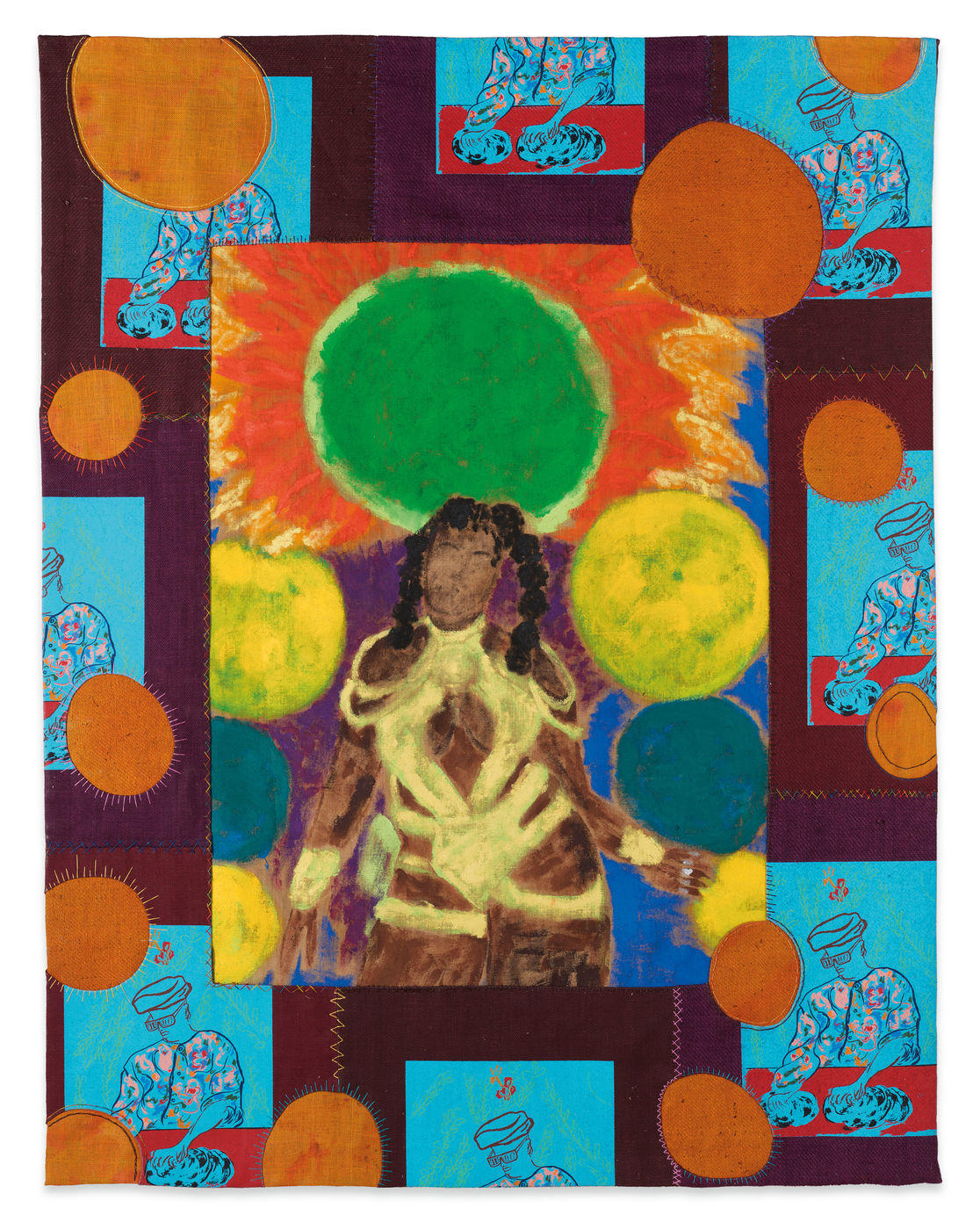

Alvaro Barrington

On the Road (TMS) A12, 2024-26

Oil, acrylic, flash, enamel on burlap / silk screen printed burlap, cotton linen, waxed cotton thread

250 × 194 cm (98.43 × 76.38 in)

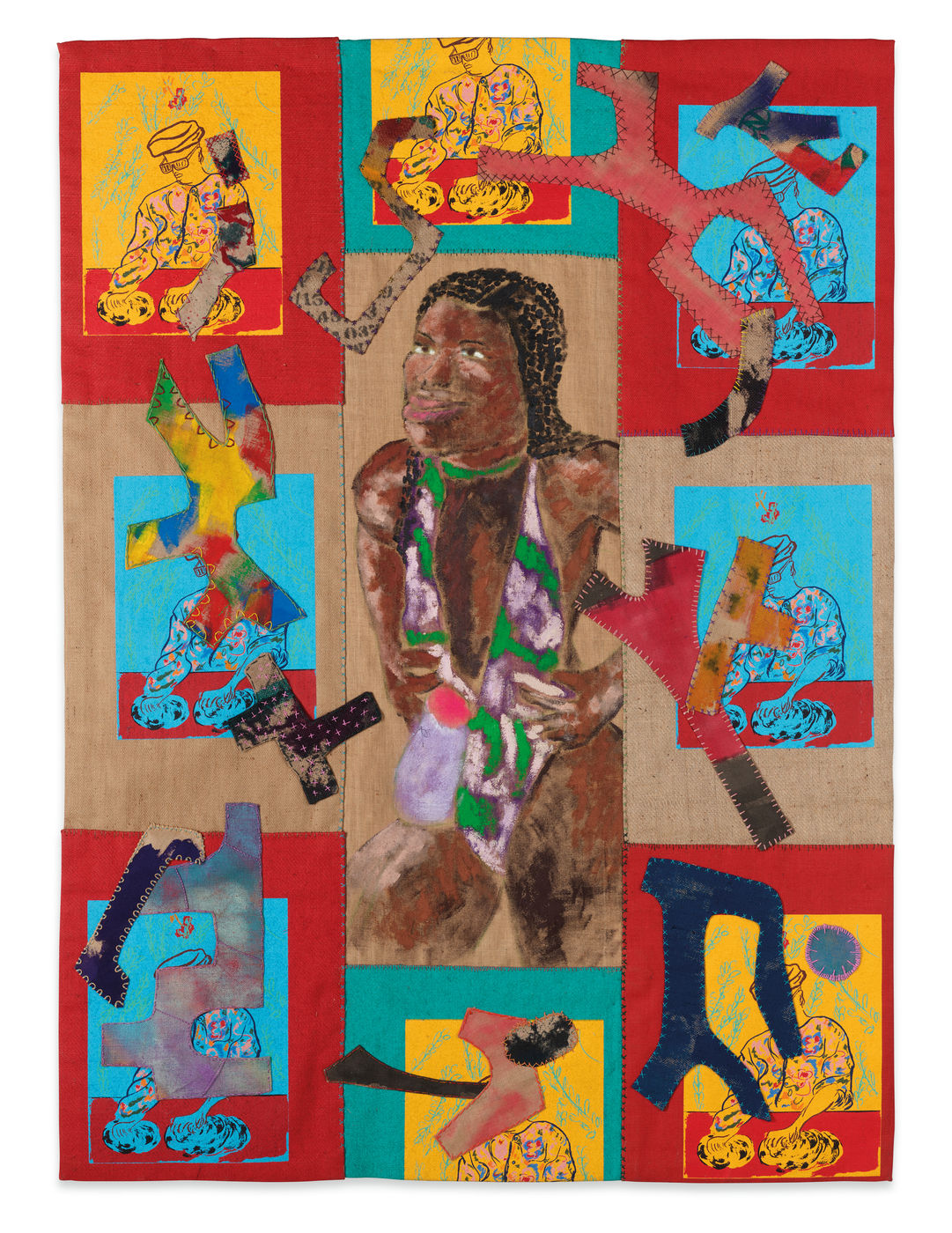

Alvaro Barrington

Oil, acrylic, flash, enamel on burlap / silk screen printed burlap, cotton linen, waxed cotton thread

269 × 191 cm (105.91 × 75.2 in)

Alvaro Barrington

On the Road (TMS) A3, 2024-26

Oil, acrylic, flash, enamel on burlap / silk screen printed burlap, cotton linen, waxed cotton thread

150 × 194.5 cm (59.06 × 76.57 in)

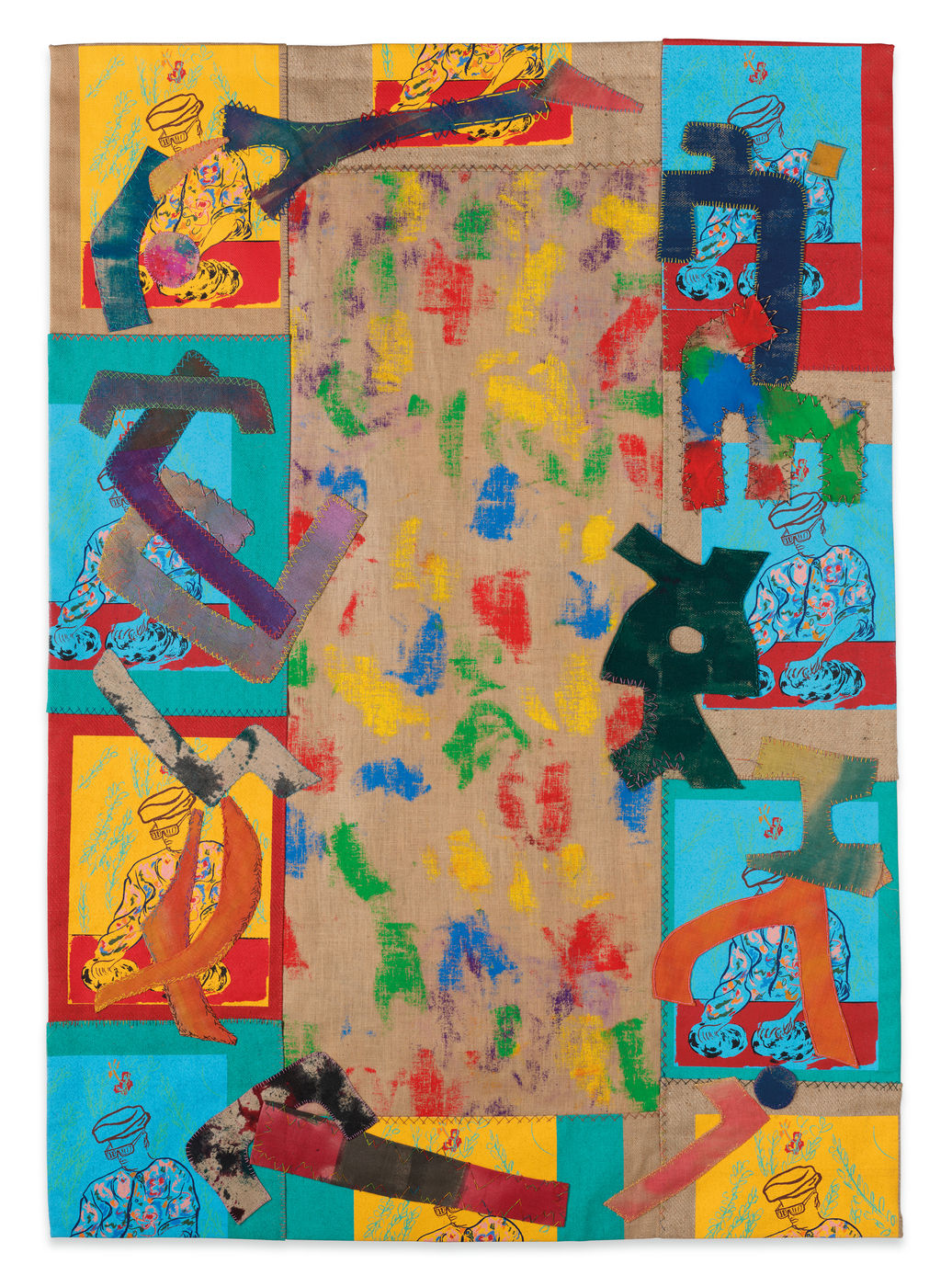

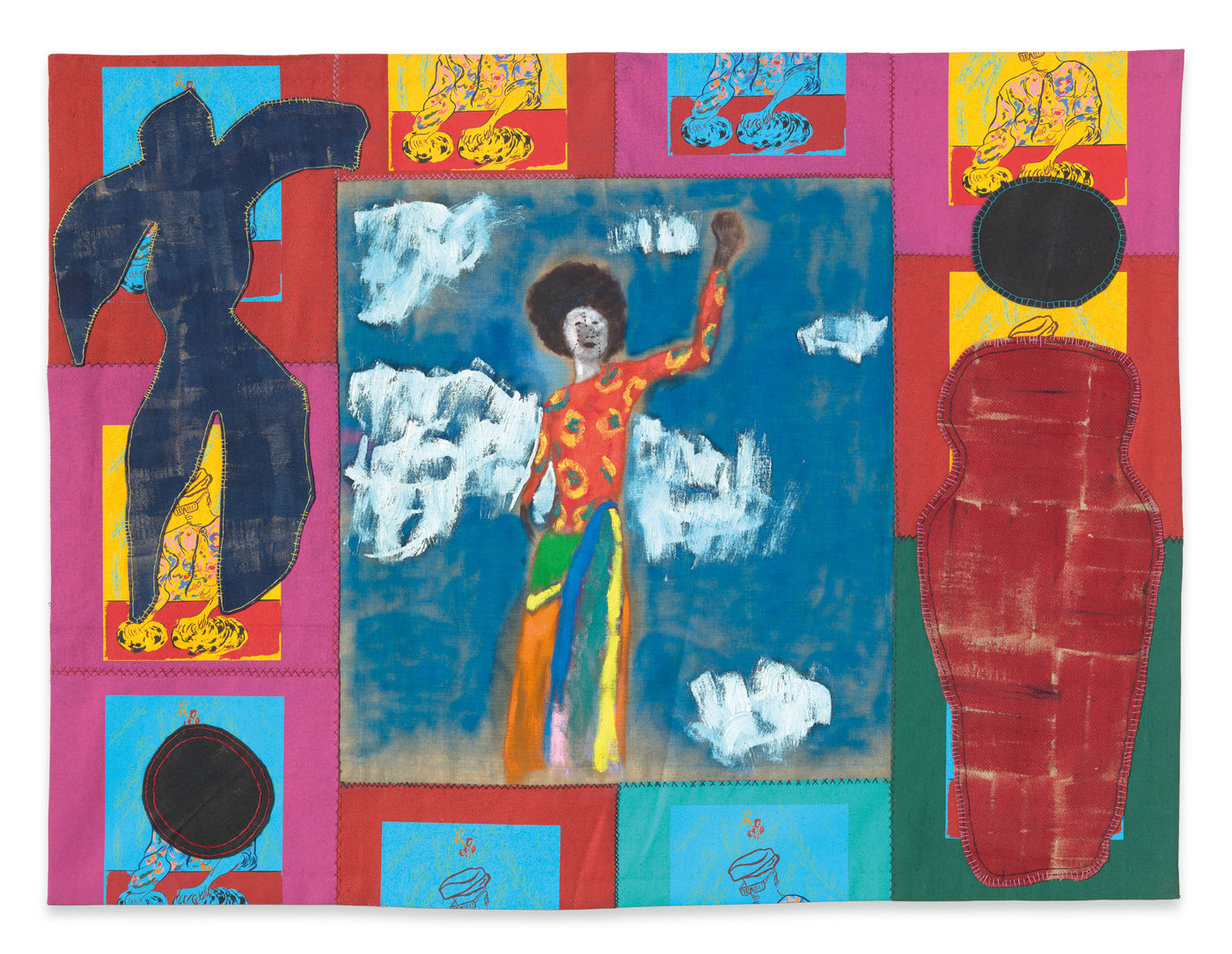

Alvaro Barrington

On the Road (TMS) A2, 2024-26

Oil, acrylic, flash, enamel on burlap / silk screen printed burlap, cotton linen, waxed cotton thread

235.5 × 200.5 cm (92.72 × 78.94 in)

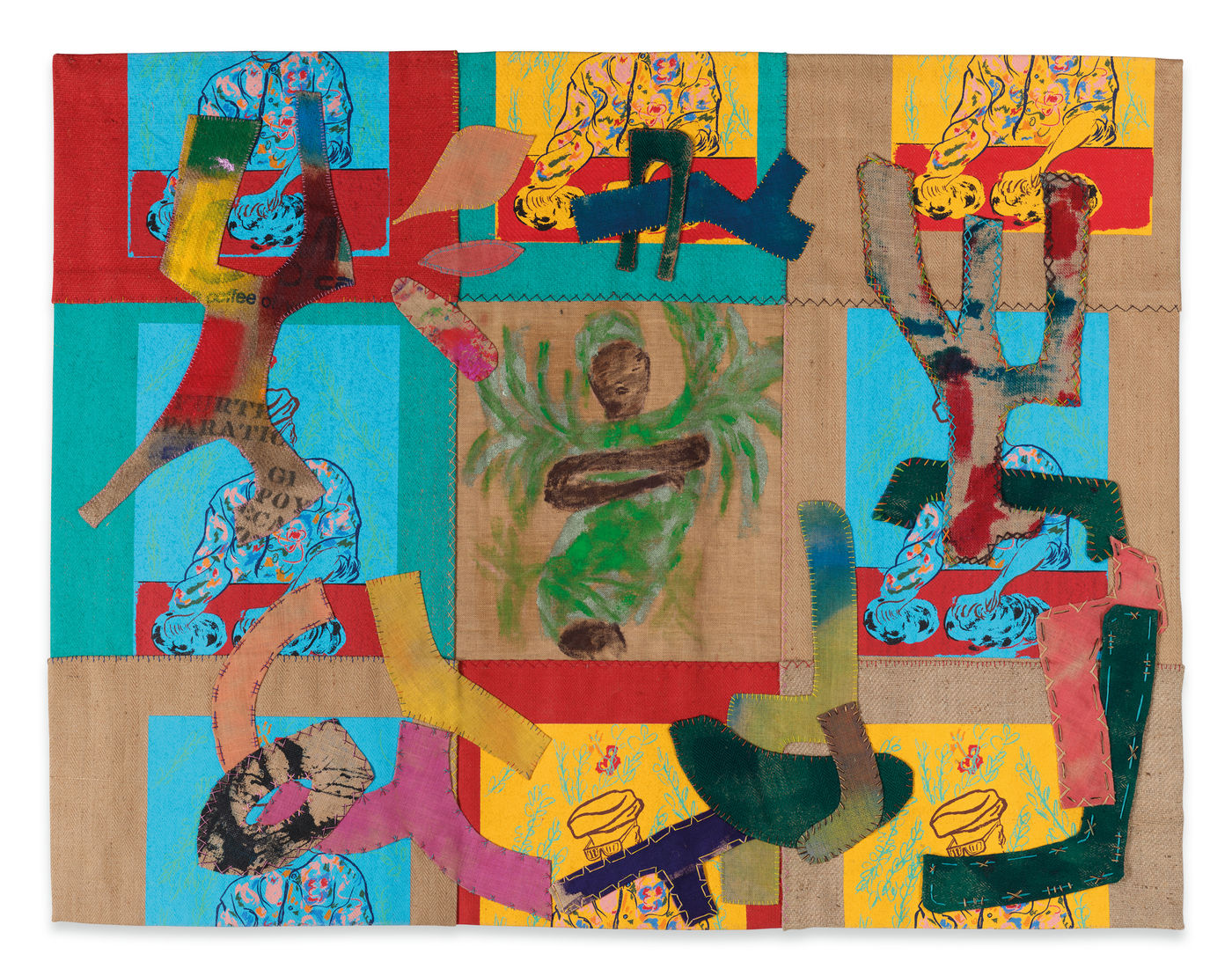

Alvaro Barrington

On the Road (TMS) A11, 2024-26

Oil, acrylic, flash, enamel on burlap / silk screen printed burlap, cotton linen, waxed cotton thread

215 × 288 cm (84.65 × 113.39 in)

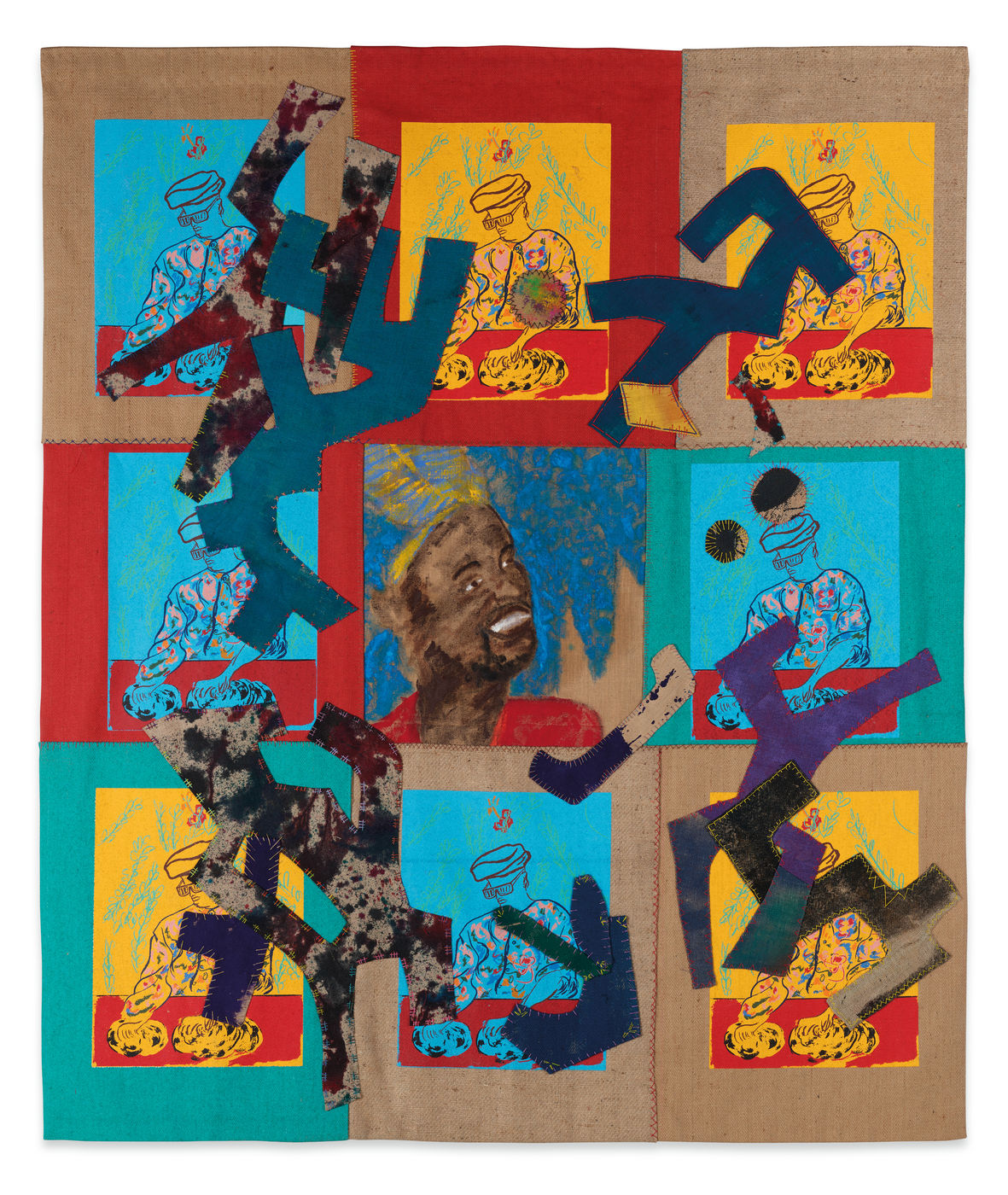

Alvaro Barrington

On the Road (TMS) A7, 2024–26

Oil, acrylic, flash, enamel on burlap / silk screen printed burlap, cotton linen, waxed cotton thread

198 × 199.5 cm (77.95 × 78.54 in)

I have this belief that we live fuller lives as human beings through trade, through the ability of trading stories, trading gifts, trading ideas. That was the overall vision. This show is a celebration of the people and places that make us feel like we belong.

by Koyo Kouoh

9 May—22 November 2026

Arsenale and Giardini, Venice

Congratulations to Alvaro Barrington on his invitation to the 61st International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia – In Minor Keys by Koyo Kouoh.