An artist in pursuit of balance

The Korean artist Lee Bul first came to public attention in the 1980s with spectacular performances denouncing gender inequality. In one striking protest against the abortion ban in her country, she suspended her naked body, upside down, from the ceiling of an arts center in Seoul.

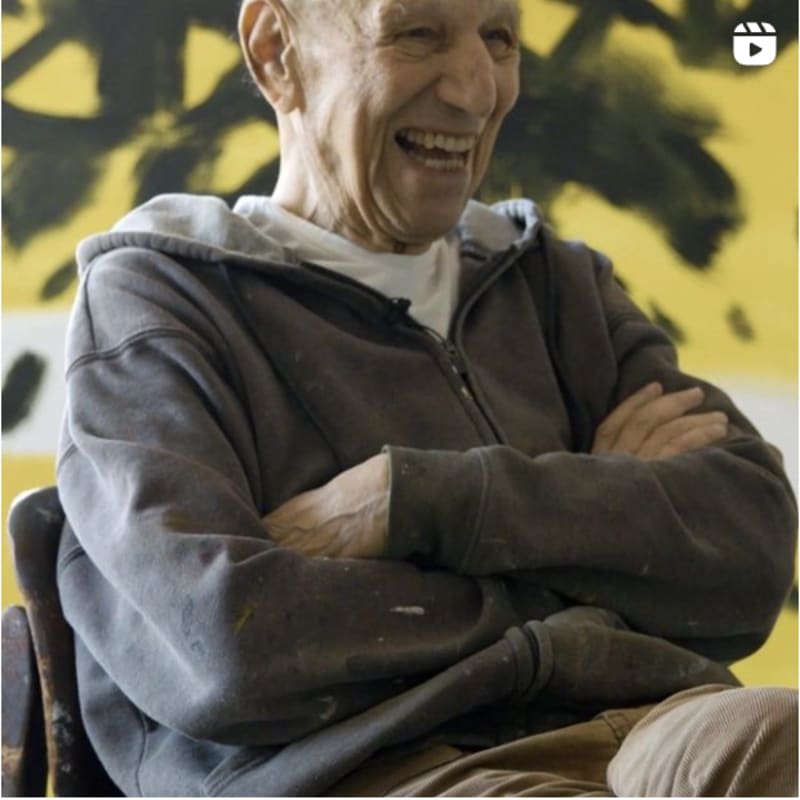

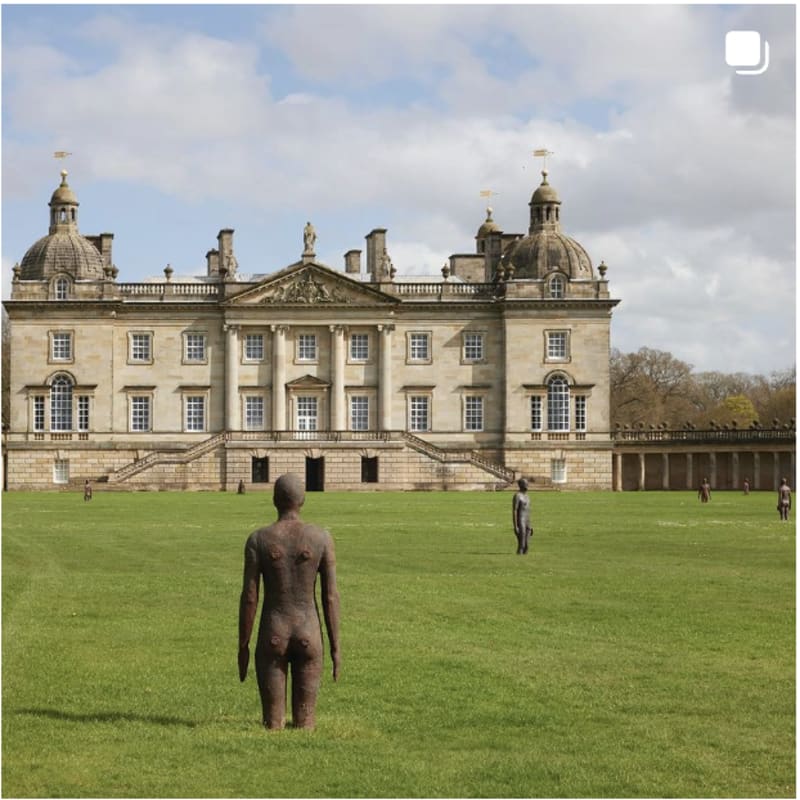

Today, Ms. Lee, 58, one of South Korea’s leading contemporary artists, dedicates her time to painting, sculpture and installation. Her art depicts the beautiful and the grotesque, earthly landscapes and sci-fi dystopias, human bodies and cyborgs — in a style that fuses art-making traditions with high-tech contemporary techniques.

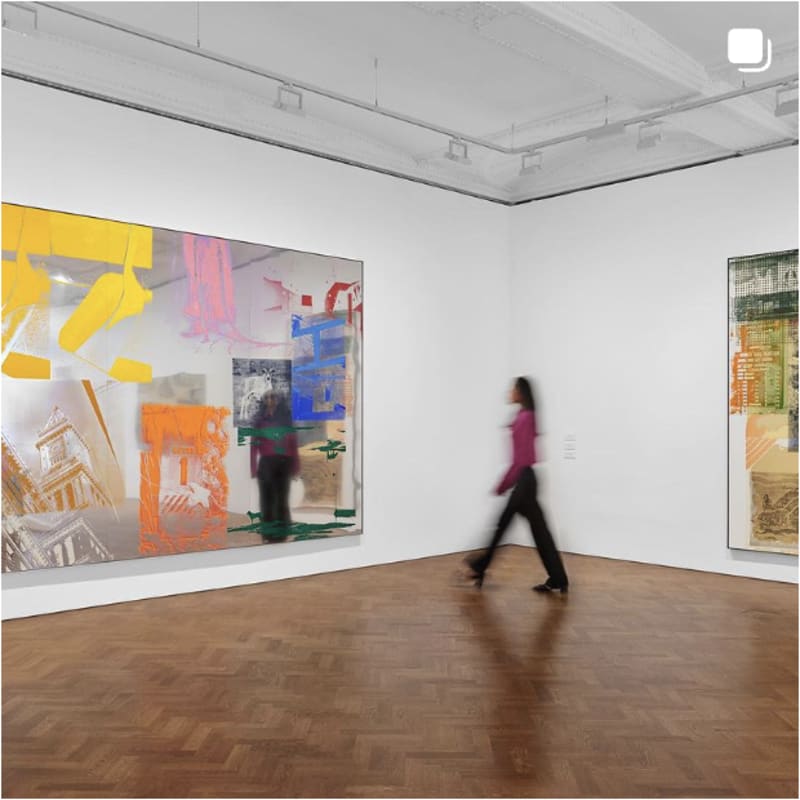

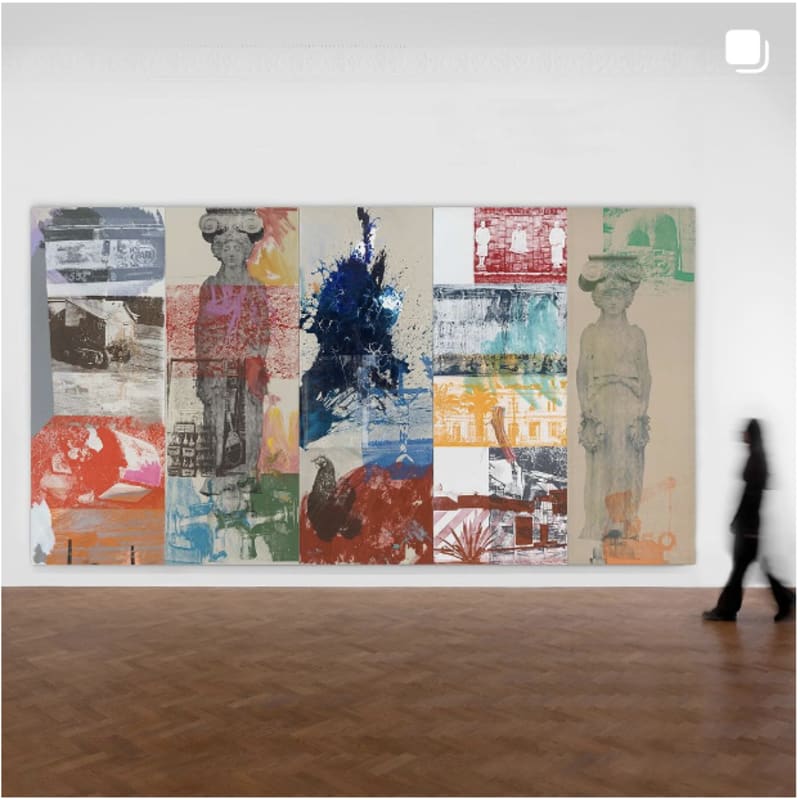

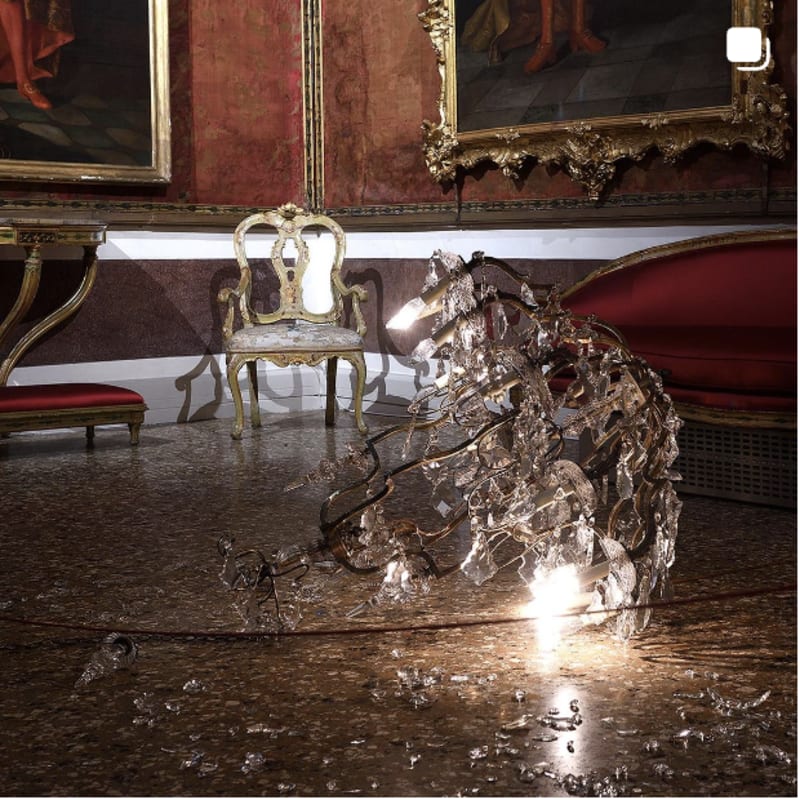

In the late 1990s, she started producing meticulously crafted sculptures of cyborgs — perfectly proportioned female bodies morphed into characters from manga and science fiction, with strange-looking limbs and armor. A decade later, she produced chandelier-like hanging installations of steel, crystal and beads that were depictions of futuristic cityscapes.

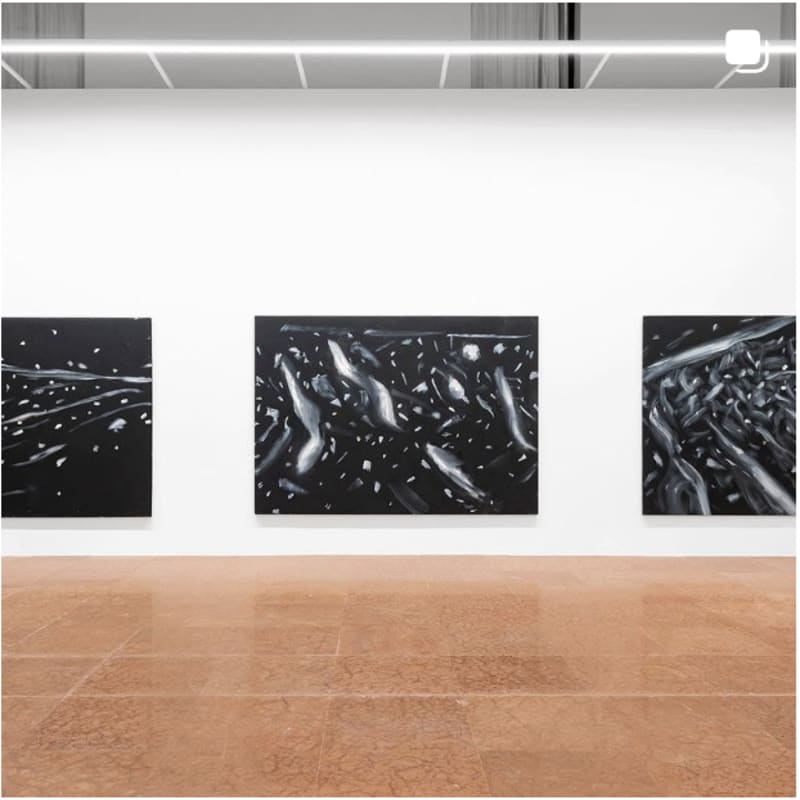

At Frieze Seoul, starting Saturday, the Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery, which represents Ms. Lee, is showing examples of her most recent series of work, “Perdu.” The series takes its name from the title of Marcel Proust’s novel “À la Recherche du Temps Perdu” (“In Search of Lost Time”). These works — with textures and protrusions that make them something of a cross between painting and sculpture — are made with mother-of-pearl and acrylic paint.

In a recent video interview, Ms. Lee spoke (with help from an interpreter) of the challenges posed by the coronavirus pandemic, her status as a female artist in South Korea and her mixed feelings about the art market. The following conversation has been edited and condensed.

The works from your recent “Perdu” series are futuristic but also classically beautiful. Do they signal a return to Korean art-making tradition?

I always use classical or traditional methods, because I don’t just want to bring high-tech materials or new technology into my art. I want to create some kind of balance.

A balance between old and new?

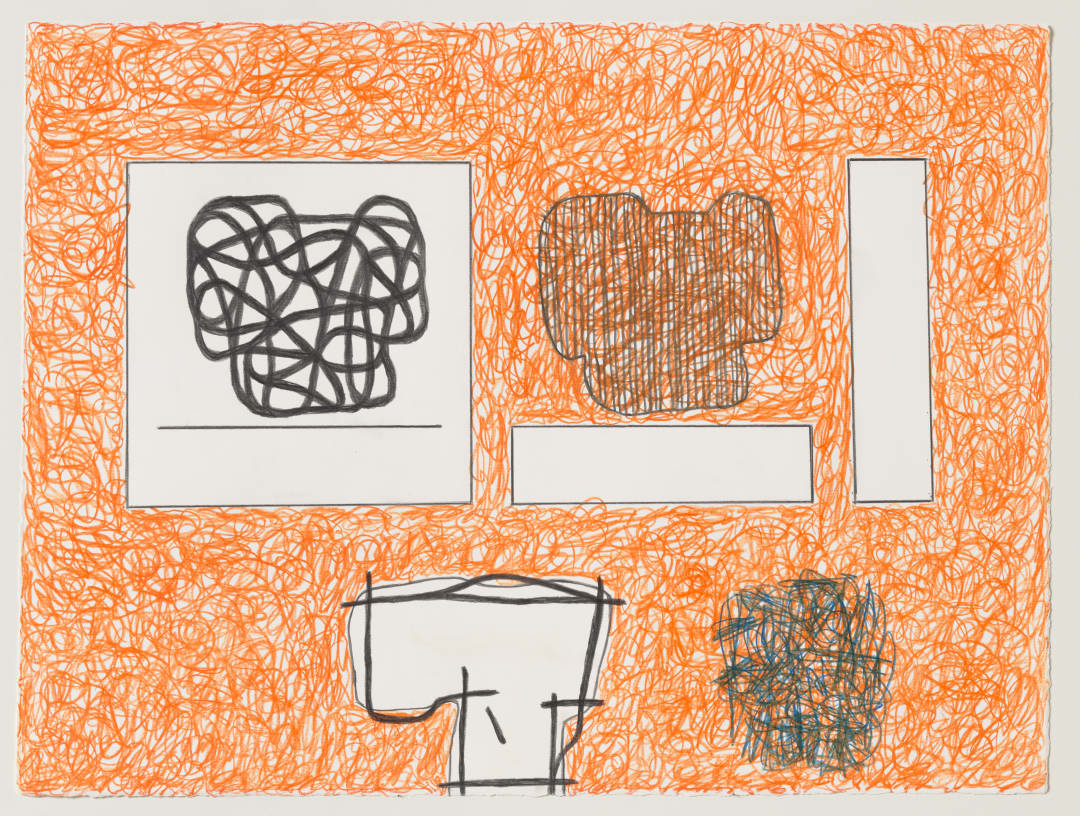

Yes. It’s very important in whatever I do, whether it be a giant sculpture or a drawing.

Why?

Because nothing is ever completely new. Ideas or visions of the future are always very old ideas. They are rooted in thoughts that human beings have entertained for a very long time — thoughts that have always been around, and that have been exhausted, even. How can these exhausted ideas still prevail? It’s a question that I’ve always been interested in posing in my work.

Curators have described your work as a combination of beauty and horror. There is great beauty in the artistic traditions of Korea, which you have studied. Why have you not dedicated your art to pure beauty

Because I don’t believe that there is such a thing as pure beauty.

We always want to define things, or to simplify things. Trying to understand the world or human beings is impossible. How can we have clear ideas or certainties about it?

My works are complex structures. When I make them, I consciously and unconsciously employ different emotions. The end results are fairly beautiful-looking but are not necessarily just beautiful. There are always three, four or more conflicting elements within them.

Because you are portraying life itself, which is much more than just beauty?

Yes.

How has the experience of the pandemic been for you?

I experienced loss at the beginning of the pandemic. Afterward, I was confronted with very big life-and-death questions. I felt the need to address those questions, to try to understand what was happening, in a way that extended beyond the experience of the pandemic itself.

Also, big sculptures and installations involve a lot of people. Making them is a long process, with many parts to it. It was not possible to make big sculptures in the pandemic. But I still wanted to work. So I looked for something that I could do alone and came up with the “Perdu” series.

The status of women has always been an important focus of your work. Why?

Because I’m a woman myself. If we want to understand ourselves and the world around us, we have to examine our own condition.

Looking at the situation of women in Korea and around the world, the problems are still ongoing, only they’ve taken a different shape. We are under the illusion that we are transitioning to a better life.

You are one of South Korea’s most prominent contemporary artists, and you’re a woman. How well are you accepted in Korean society?

It’s a very interesting question. Although the situation has improved a little, it seems, still, that in Korean society, women are only accepted when they don’t assert their gender, or when their status transcends social class.

Artists are a very special category. They don’t belong to any particular social class. So when someone says: “She’s a woman artist,” there is less resistance.

I have been working as an artist for almost 40 years now. Maybe I have reached an age in which people no longer view me as a woman artist, but rather as an artist.

Also, my practice has become a kind of precedent for the younger generation of Korean women artists, who are passionately engaged in their own practices. These younger artists are having good careers, and developing naturally, perhaps because of this precedent.

As an artist with international representation, you are a part of the art market, and you benefit from it. At the same time, prices at the very top of the art market have exploded, and some works sell for nine digits. What are your thoughts on this?

The current situation does not make sense. Human desire is always bigger than anything we can ever imagine. That’s why it’s difficult to analyze.

There are certain danger signals. No matter how hard I try not to be associated with these aspects, one way or another, I am. So my strategy is, as much as possible, to keep a distance.

As for whether the art market benefits me, in some ways, it does. In other ways, it is a real distraction.