What Joseph Beuys means to a Caribbean-American painter today Alvaro Barrington in Conversation with Eva Karcher

Painting music: Alvaro Barrington on hip-hop and Matisse, his experiences as a teenager in New York City and the NFT phenomenon.

By Eva Karcher | Translation by Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac

Alvaro Barrington, the title of your exhibition at the Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac in Paris quotes a line from a song by the Canadian rapper Drake. You have dedicated two works in the show to superstars of hip-hop, Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G. What do you owe to this extremely popular style of sound?

Almost everything. This music feeds me my energetic impulses. The sound of an era has always been an important source of inspiration for visual artists. For Henri Matisse, for example – to whom I also dedicate a work. In the thirties, he frequented the Black clubs in New York and was passionate about jazz. The lines of his late drawings improvise rhythms and sounds. The real music of Paris is jazz for me, I felt that when I was there just now. With the paintings in my exhibition, I am trying to paint music. The second, related theme is the lockdown.

How does it manifest in the pictures?

It was interesting to see how many friends spent the time of isolation with working on themselves. Doing things, they had been putting off like writing scripts, doing yoga, cooking, composing. Being with themselves, each in their own zone. Like dancing by yourself. There are some pictures of that, too.

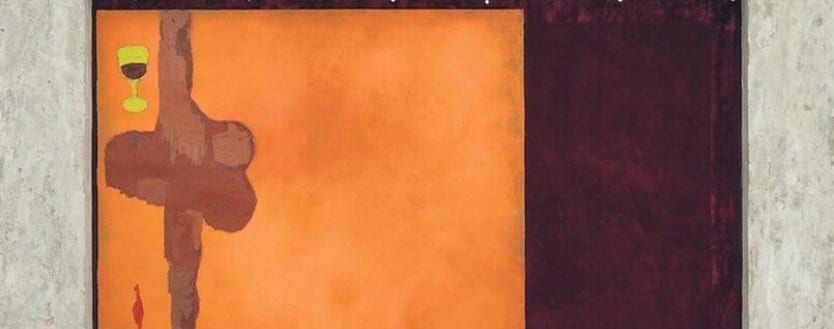

You mix figuration and abstraction and combine different materials and techniques: Cement, burlap, silk, velvet and embroidery, sewing, painting, drawing. You were born 1983 in Venezuela and spent the first eight years of your life with your grandmother in Grenada in the Caribbean – where dub was around in the late sixties. This genre of electronic music evolved from reggae and remixes melodies and rhythms. Does that correspond to your way of working?

Yes, but I am a child of hip-hop, the most powerful pop music movement on the globe. When I was eight years old, I moved to Flatbush in Brooklyn with my mother. Rap is just as much about sampling and mixing. It's true, Black music culture – soul, funk, reggae, R & B – is the one licence I have. At the same time, I am in a constant dialogue with art and art history. Take Matisse again: He listened to jazz. At the same time, he studied Chinese calligraphy and ink painting, and thinking about how he could combine this sound and this aesthetic, which to him felt like they belonged together.

You also mention artists like Louise Bourgeois or Helen Frankenthaler as references for your work.

Through their art, I learn to understand their humanity. For Frankenthaler, who was Jewish like Lee Krasner, Mark Rothko or Philip Guston, making art was an act of proving to herself that she had survived. Abstract expressionism after the end of the Second World War was in some ways an existentialist movement. The artists lived in nature, in the mountains, by the sea, they staged their art as a drama and thus felt alive.

With your exhibition, do you also want to show that Black culture plays a central role in art history?

Basically, every culture is an essential part of art history, including the culture in a tiny village in the Amazon. The people there may not know who Michelangelo was, but they live their respective culture, and this is part of art history.

I don't distinguish between high and low, between elite and popular art. For me, every culture and every art form is about an exchange. About starting a conversation. There is a common misconception that artists are born geniuses with universal creative powers. That is so far from the truth!

In the words of Joseph Beuys, who would have celebrated his 100th birthday in May: “Everyone is an artist.”

Exactly! Beuys is one of my philosophical-artistic giants. He shaped my understanding of art as a lived process. Art doesn’t have to be a picture on the wall, it can also mean founding a green political party. We artists are part of the cultural imagination of the world, we are shaped by the same perceptions and impressions. Beuys’ revolutionary sentence applies more than ever. Everyone has the right to be creative.

From the African-American artist Kara Walker comes the sentence: “Whatever I do, it’s political.” Does that also apply to you?

Everything I do has political consequences. It’s true for all of us, we just don’t realize it enough. One painting in my show, “Back that azz up (Black dress)” shows a woman in a black cocktail dress, a friend.

She can’t go out during Corona, so she wears the dress for herself. This is also a political statement.

Unfortunately, once again there is an upsurge of atrocious racism. Alvaro, have you also experienced discrimination?

Yes. In the eighties and early nineties there was this devastating crack epidemic in the US with mass arrests. I was a kid in Brooklyn and saw friends and neighbours, some as young as twelve, thirteen years old, being sentenced to up to twenty years in prison! Instead of helping them, curing them! I was deeply disturbed by this. In America, there is this inhumane practice of mass imprisoning people of a different skin colour, which is rooted in systemic racism. On the other hand: the fact that I grew up in a place where I experienced brutality and murders around me helped me not to prejudge anyone.

What do you think of New York gallery owner David Zwirner’s announcement that he is opening a new gallery with Ebony L. Haines as director and an exclusively Black team?

It’s a complex issue. Did you know, that Black women are among the population with the fastest growing wealth? It could well be the case that gallery owners have done too little to include these women - and men, of course.

Back to Beuys and at the same time to the currently so hyped digital certificates of authenticity, the NFTs or non-fungible tokens. They make it possible for only one file to be considered an original among a multitude of identical copies. Many are praising them as miracle weapons that will democratise the market and, above all, creative production. Do you believe that too?

This NFT thing is a brand-new system that allows digital artistic works to be paid for directly. That would really mean a democratisation of creative productions à la Beuys and would be a breakthrough. But I think at the moment we are in a bubble. Currently, Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey is selling his very first tweet as a non-fungible token on the Valuables platform. A few days ago, the highest bid was 2.5 million dollars.

But will Twitter still be remembered in 15 years? Just like the social network Myspace. Everyone thought it was the biggest thing on the internet, but does anyone still use it? Maybe the same thing will happen soon with Instagram, who knows? With the NFTs, I also wonder about the concept of art.

You could present one of your works in this way?

This has to evolve. I'm very interested in everything digital. At the moment, the most creative minds come from Silicon Valley. However, the internet has become the biggest surveillance machinery for global capitalism. We are the generation of artists that needs to take back the control over the digital. We must reclaim the internet as a free space.