Lee Bul's Utopian Encounters with the Russian Avant-garde

In 2005, Lee Bul turned her attention to the 'utopian shadows' cast by modernist architectures, from Joseph Paxton's Crystal Palace, the stage for London's 1851 Great Exhibition, to Vladimir Tatlin's iconic model for the Monument to the Third International (1920).

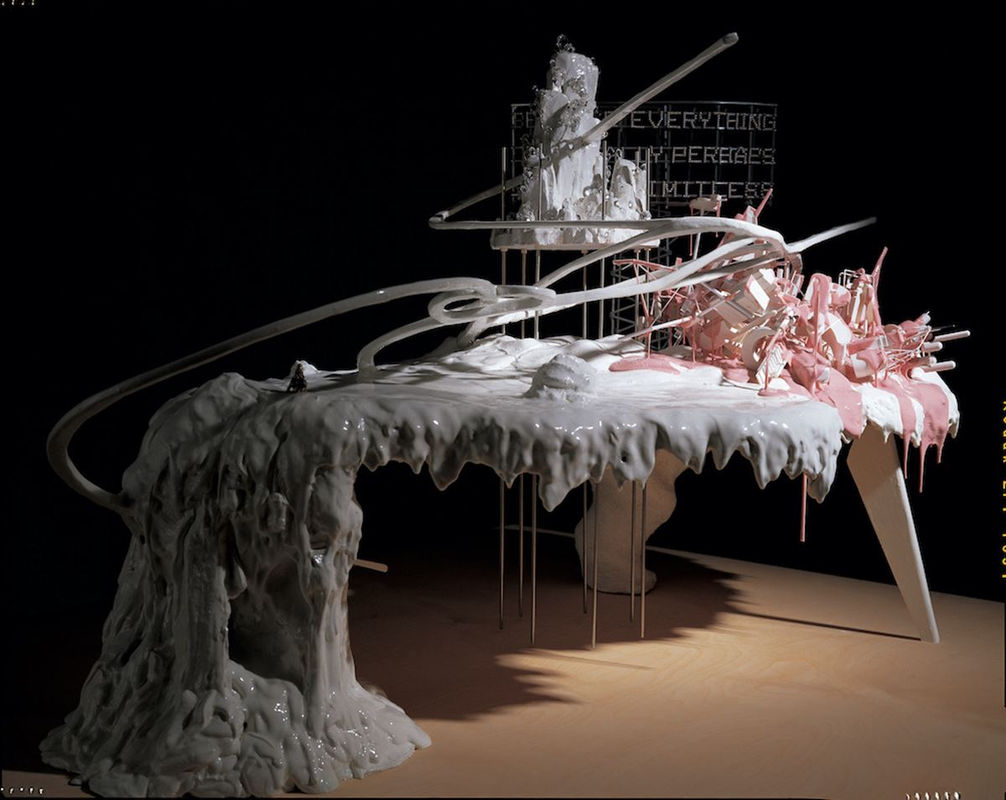

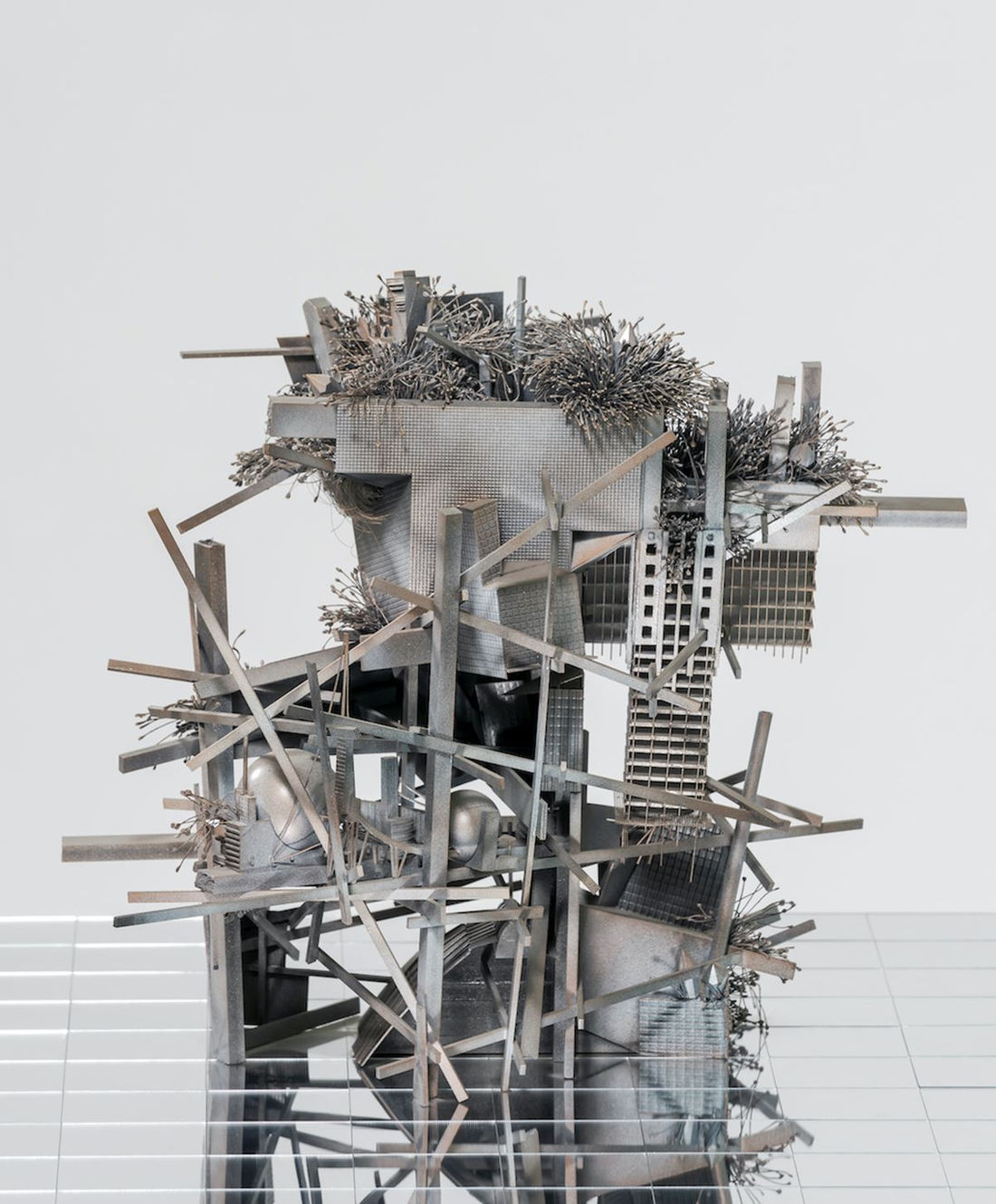

'Mon grand récit' was the first series to emerge from this shift, central to which is Mon grand récit: Because everything... (2005): a table-top landscape weighed down by cascades of white epoxy and a mash-up of models for unrealised Constructivist buildings and monuments steeped in pink resin. Hovering over the scene, an LED sign fixed to a metal armature quotes fragments from Paul Bowles' 1949 novel The Sheltering Sky: 'Because everything', 'only really perhaps', yet so limitless'.

The series' title responds to Jean-Francois Lyotard's definition of postmodernity as an 'incredulity' towards meta- or grand narratives. By placing 'mon' (or 'my' in English) before 'grand récit', Lee Bul sought 'to convey a slightly ironic, melancholic stance toward that idea', at once recognising the impossibility of grand narratives while upholding the need for stories—'albeit subjective, imperfect, incomplete'—'that can serve as consolation in [their] absence'.1

A sense of consolation feeds into Lee Bul's first solo exhibition in Russia at St. Petersburg's Manege Central Exhibition Hall, Utopia Saved (13 November 2020–31 January 2021). Curated by Sunjung Kim and SooJin Lee, the show brings together environmental installations, architectural sculptures, and design drawings created since 2005, 'to provide a comprehensive view of the artist's journey of inquiry into the history of modernity and modernism.'

Organised with the Gwangju Biennale Foundation as part of the Year of Cultural Exchange between Russia and South Korea, which celebrates 30 years since diplomatic ties between the two countries were established, Utopia Saved also marks a first-time encounter between Lee Bul's works and those by artists of the Russian avant-garde that influenced them.

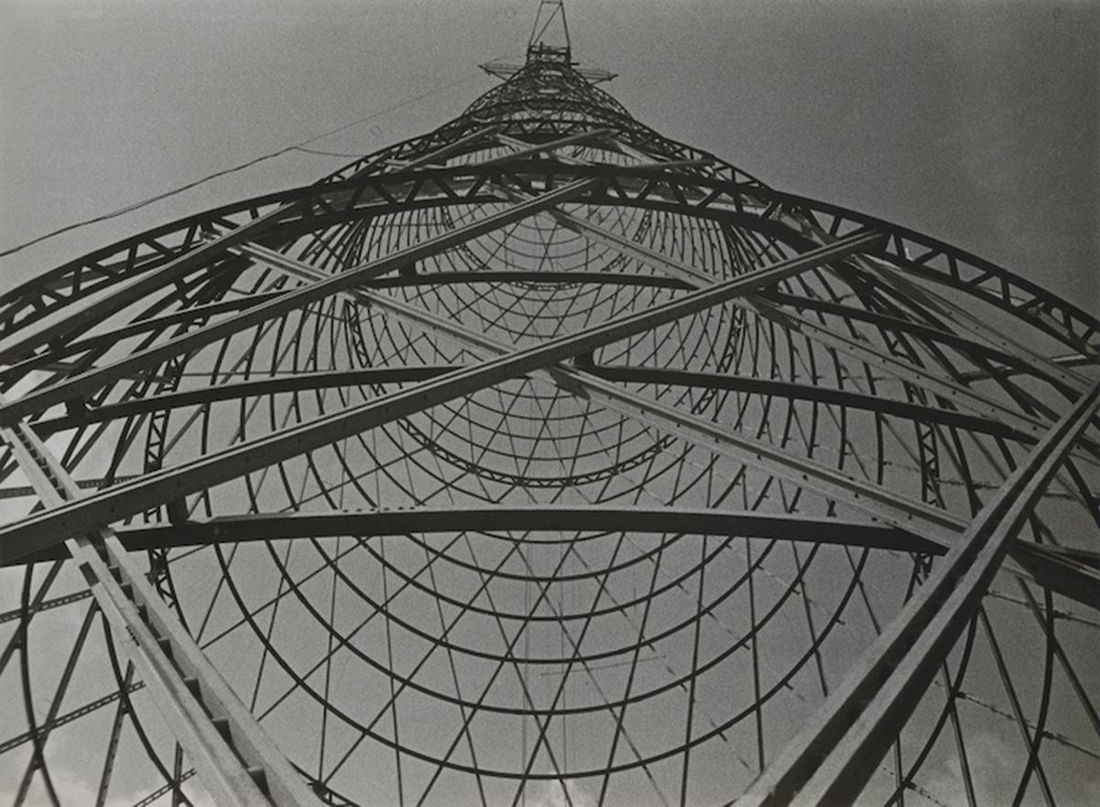

Among the historical pieces on view is architect Iakov Chernikhov's epic Composition No. 152: 'Factory/City', a fuchsia-toned design of overlapping cylindrical towers from the series 'Foundations of Contemporary Architecture' (1925–1929), and a dramatic 1929 black-and-white photograph zooming in on the wrought-iron lattice of the Shukhov radio transmission tower in Moscow by artist Aleksandr Rodchenko.

The zeppelin appears throughout these historical works, whether a tin model by scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky from between 1912 and 1914, the image of a USSR-V6 dirigible floating over Moscow captured by photographer Yakov Khalip between 1936 and 1937, or the blimp suspended amid hazy strokes in Aleksandr Labas's 1935 oil painting, The City of the Future.

A striking airship is the centrepiece of Lee Bul's most recent installation series, 'Willing To Be Vulnerable' (2015–ongoing), which recreates symbols of modernity at monumental scale using lightweight materials. In Willing To Be Vulnerable — Metalized Balloon (2015–2016/2020), a giant 17-metre-long aluminium foil balloon coated in thin cloth is designed after the doomed LZ129 Hindenburg, at first a symbol of progress before a deadly 1937 crash in New Jersey saw the vessel consumed by fire in seconds.

As exhibition curators Kim and Lee note, works from 'Willing To Be Vulnerable' are shown with fans that 'blow air into the exhibition space, causing the lightweight materials and surfaces to continually flutter'—an effect they liken to 'the vulnerable skin of a small living creature.'2

In their catalogue essay, the curators use the concept of skin as a point of entry into Lee's practice by way of the artist's childhood memories. 'A sheet of paper was all that stood between my skin and others',3 Lee Bul has recalled of a traditional wood-framed paper door, which marked the flimsy boundary between her home and the military village beyond it, just outside of Seoul.

To think about skin as both a divider and connector 'explains much about [Lee Bul's] work in general, and her post-2005 architectural sculptures and large-scale installations in particular'4, write Kim and Lee.

The artist, who once commented that 'all surfaces are battlegrounds', 'often play[s] with the surface,' the curators write, 'draw[ing] attention to its complexities and delicacies'.5Whether in early performances like Sorry for suffering — You think I'm a puppy on a picnic? (1990), for which Lee Bul wore 'soft sculptures' embellished with organs, limbs, and tentacles around Seoul and Tokyo, or sculptural installations like Majestic Splendor(1991–2018), which adorned the scales of fresh fish with sequins and beads.

Skin is Lee Bul's point of relation and refraction—at once a boundary, threshold, and mirror. This idea extends to the landscape, whether the true-view painting genre privileging essence over realism in traditional Korean art, the divisions of the Korean peninsula following World War II, the rapid urbanisation that transformed South Korea under Park Chung-hee's postwar regime, or the rubbery surfaces of Mon grand recit: Because anything...

'Contrary to what some may assume,' Kim and Lee write, Lee Bul 'is not particularly interested in pursuing utopia or suggesting utopian ideas through her works. Rather, she is curious about exploring the ideas surrounding utopia and modernity as they connect to the reality she feels through her skin.'6

Utopia Saved, in this light, is as much about sensing utopia's textures as it is about feeling its loss. A fact that brings to mind Cole Roskam's contribution to the exhibition catalogue, which points out that, while it is often understood that the utopian projects visualised by the Constructivists were failures because they were never built, the truth might be more nuanced.

Tatlin, Roskam writes, was a conceptual architect, much like the German expressionist architect Bruno Taut, who in 1919 proclaimed 'Let us consciously be "imaginary architects"!' Both were associated with early 20th-century avant-garde architectural movements, whose theories 'were imagined first and foremost as conceptual catalysts designed not necessarily with physical materialisation in mind, but rather in the name of generating specific political, social, or cultural effects.'7

Taut was known for designing the Glass Pavilion at the 1914 Cologne Werkbund Exhibition, which symbolised the ideas of socialist novelist Paul Scheerbart, whose words espousing a future embodied by glass architecture appeared on the construction's exterior, like 'Coloured glass destroys hatred'.

His drawings The Crystal Mountain (1918), which visualises a city carved into the Alps, and The Cathedral Star (1918), a design prototype for Lee Bul's sculptures, were a core influence on the artist's architectural turn. In 2007, Lee Bul initiated the series 'After Bruno Taut' and 'Sternbau', both presenting broke-down chandelier-like constructions suspended from ceilings with crystal, glass, and acrylic beads woven into and dripping from metal armatures often spun into whirls.

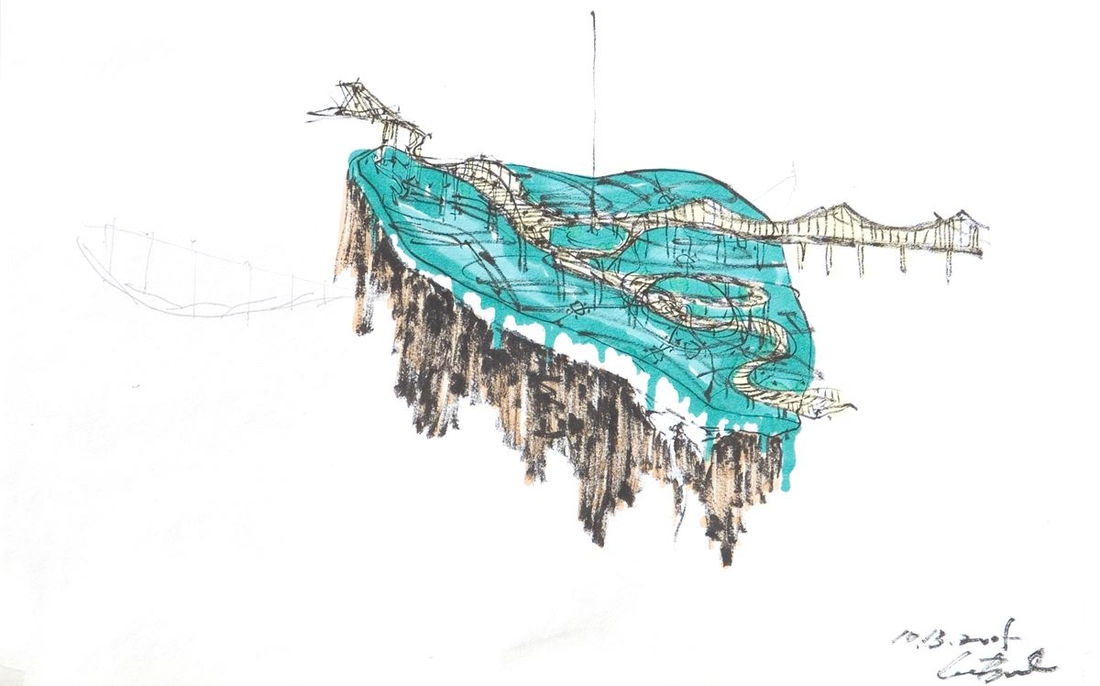

The 2007 work After Bruno Taut: Beware the sweetness of things is a sculptural translation of Taut's glittering alpine city—a haunting homage to a vision of an ideal city that echoes architectural models like Untitled ("Buried memory tableau") (2008), which manifest the complex, exuberant, yet perhaps impractical, two-dimensional lines of Constructivist design in three dimensions.

This all-too-human ambition feeds the marvels and tragedies of utopian visions. Those desires to harness nature, to claim victory over it, seem to have a tendency to bring about downfalls—a fate foretold in the tragedy of the ancient architect Daedalus, whose son flew too close to the sun.

Echoes of such destinies reverberate in Lee Bul's 'Civitas Solis' series, initiated in 2013, which references Italian philosopher Tommaso Campanella's 1602 book The City of the Sun. Campanella's narrative imagined a world of equals, where everyone lives in palaces; it inspired the drawings of Russian Constructivist architect Ivan Leonidov.

Lee Bul has said that the idea for 'Civitas Solis' came to her as she gazed over Tokyo at night from an airplane post-Fukushima, and felt a sense of mourning in the flickering lights below—a memory that seems to feed into Civitas Solis II (2014), an installation in which circular arrangements of hanging lights illuminate cracked mirrors that appear like landmasses covering floors and walls.

Drawing on a birds-eye view that looks down on the modern city from above, Civitas Solis II reverses the perspective of the 'Sternbau' series, which references Taut's drawings of celestial bodies transforming into urban architectures, like a vision in the sky to aspire to, or a wish on a star to be realised.

In both cases, a kind of neck-aching longing seems to anchor Lee Bul's ambiguous perception of utopia as an 'inherent condition' defined by as much by its sense of proximity as the inevitable realisation of its impossibility. 'Still', the artist says, 'we dream'.8—[O]

______

1 Lee Bul: Utopia Saved, Manege Central Exhibition Hall, exhibition catalogue, edited by Sunjung Kim, SooJin Lee, Anna Kirikova (Autonomous non-profit organisation for the development of art and culture, 2020), p. 236.

2 Lee Bul: Utopia Saved, Manege Central Exhibition Hall, exhibition catalogue, edited by Sunjung Kim, SooJin Lee, Anna Kirikova (Autonomous non-profit organisation for the development of art and culture, 2020), p. 57.

3 Lee Bul: Utopia Saved, Manege Central Exhibition Hall, exhibition catalogue, edited by Sunjung Kim, SooJin Lee, Anna Kirikova (Autonomous non-profit organisation for the development of art and culture, 2020), p. 30.

4 Ibid.

5 Lee Bul: Utopia Saved, Manege Central Exhibition Hall, exhibition catalogue, edited by Sunjung Kim, SooJin Lee, Anna Kirikova (Autonomous non-profit organisation for the development of art and culture, 2020), p. 32.

6 Lee Bul: Utopia Saved, Manege Central Exhibition Hall, exhibition catalogue, edited by Sunjung Kim, SooJin Lee, Anna Kirikova (Autonomous non-profit organisation for the development of art and culture, 2020), p. 45.

7 Lee Bul: Utopia Saved, Manege Central Exhibition Hall, exhibition catalogue, edited by Sunjung Kim, SooJin Lee, Anna Kirikova (Autonomous non-profit organisation for the development of art and culture, 2020), p. 98.

8 Lee Bul: Utopia Saved, Manege Central Exhibition Hall, exhibition catalogue, edited by Sunjung Kim, SooJin Lee, Anna Kirikova (Autonomous non-profit organisation for the development of art and culture, 2020), p. 26.