Tom Sachs Paints His Own Picasso Interview of the artist by Jeremy Olds

By Jeremy Olds

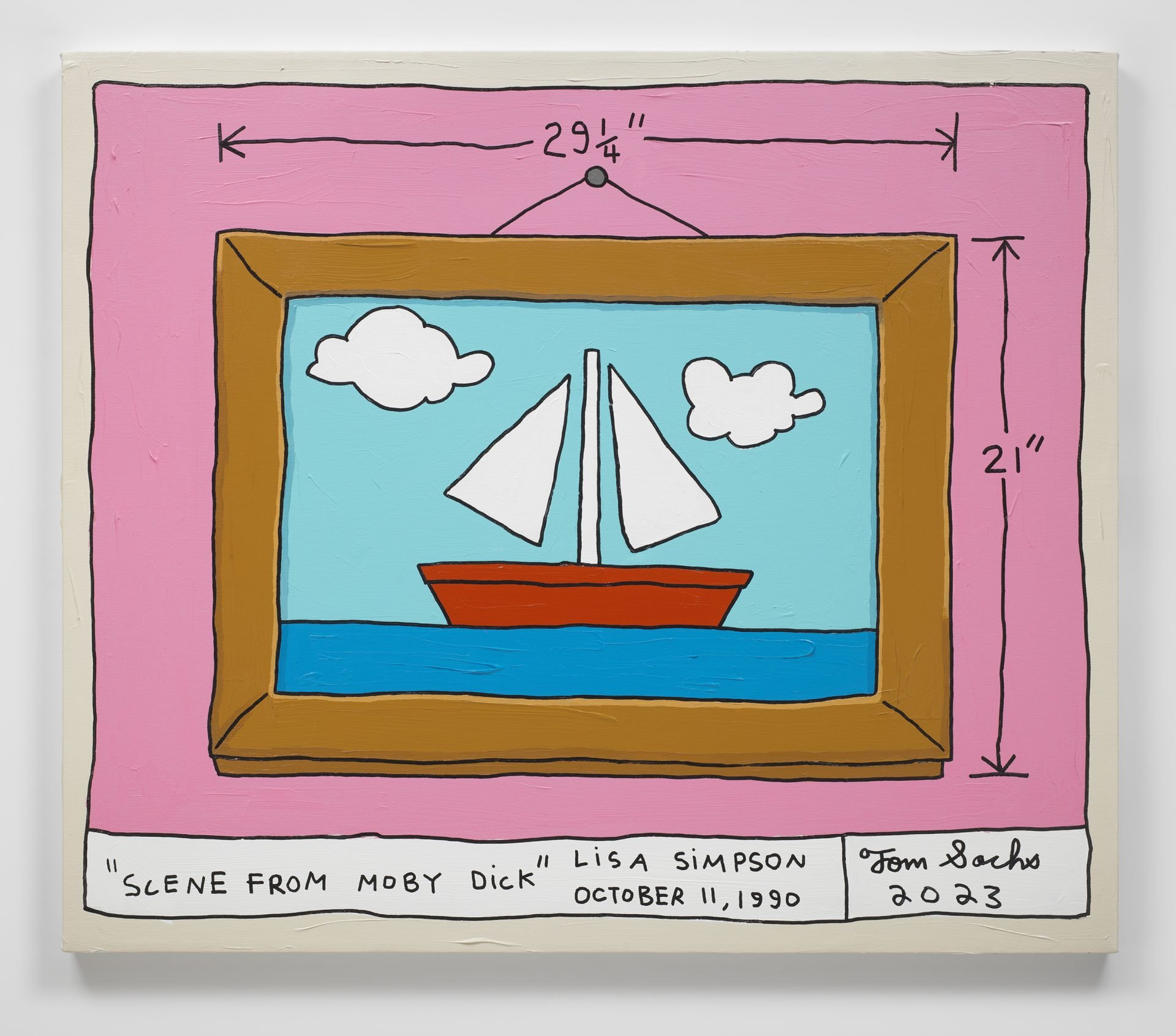

“Behold, the greatest painting of all time,” announces the American artist Tom Sachs to a small group gathered before one of his latest works: a recreation of the sailboat painting that hangs above the living room sofa in The Simpsons. Sachs estimates it’s one of the most-viewed paintings in history, more recognizable maybe than any of the still life paintings by Pablo Picasso he has recreated in the gallery adjacent.

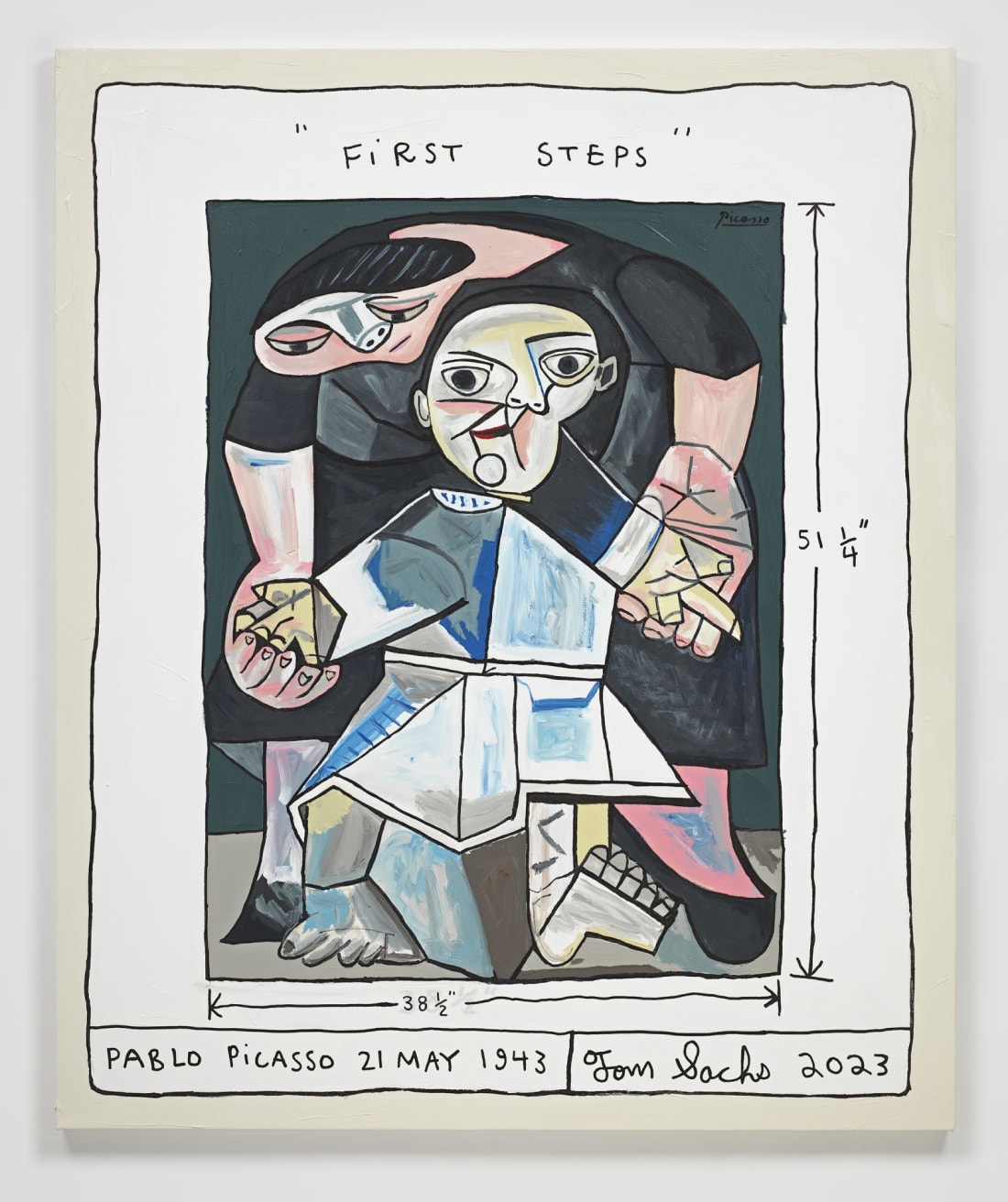

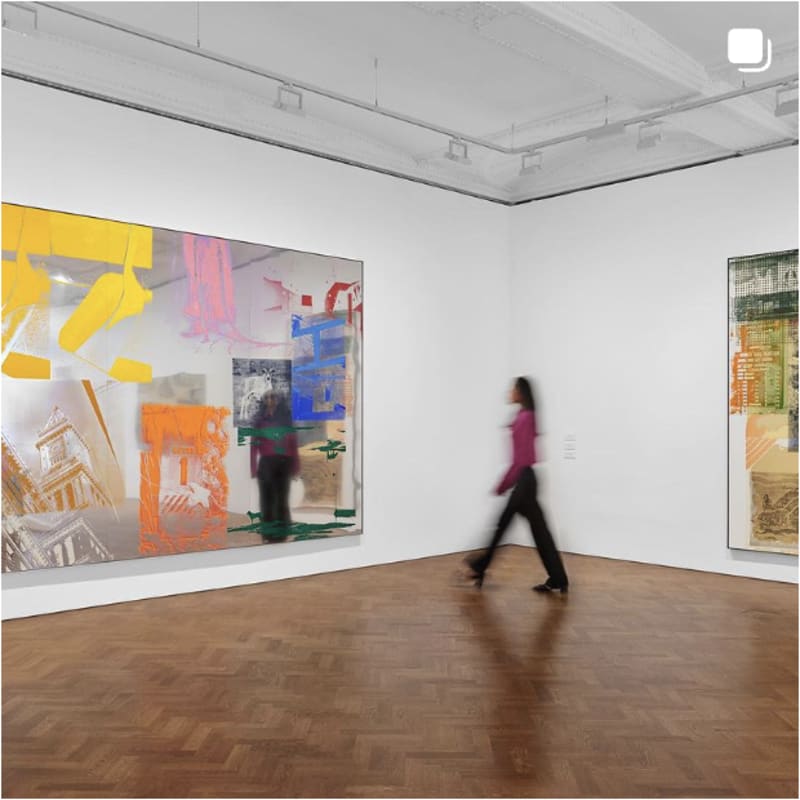

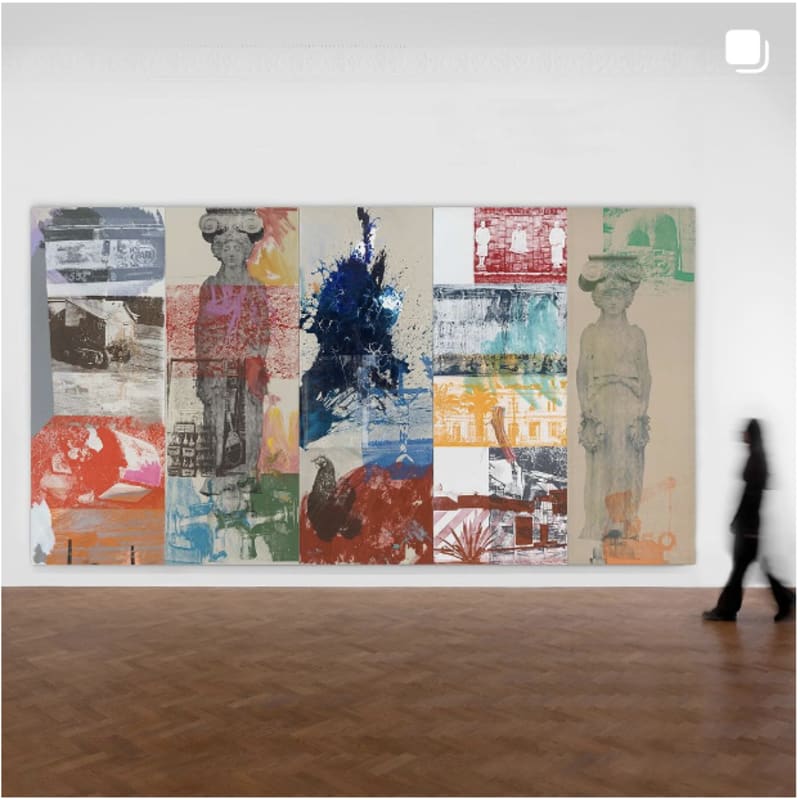

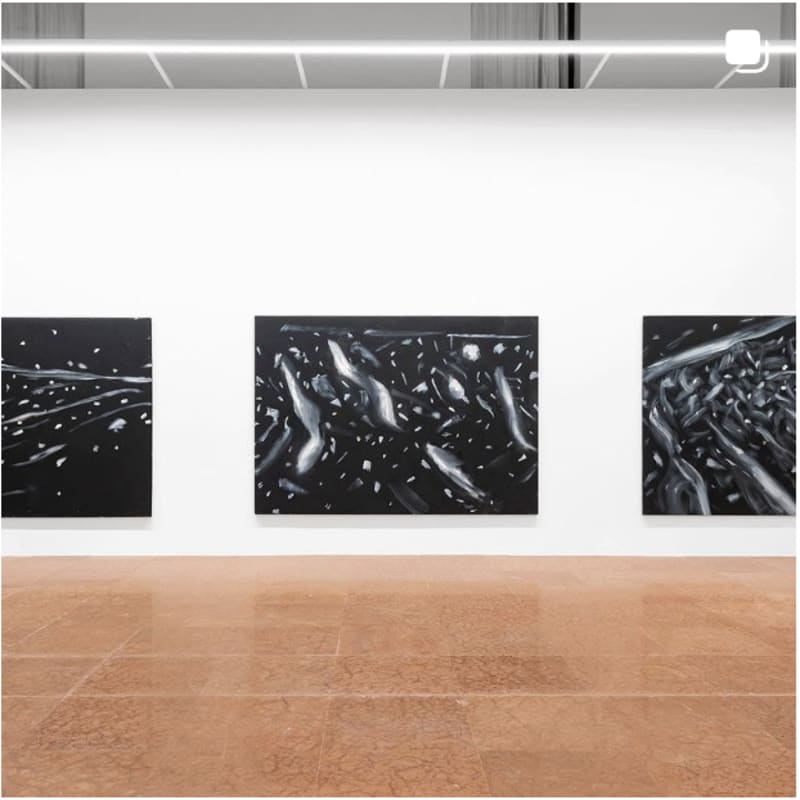

For his latest exhibition “Painting,” which opened at Thaddaeus Ropac gallery in Paris last week, Sachs delves into the oeuvre of the Spanish artist, creating his own replicas of still life paintings from Picasso’s ‘War Years’ (1937-1945). Adding to this, Sachs recreates works by two others: Rotorelief (1935) by Picasso’s rival Marcel Duchamp, a birds-eye-view of colorful discs that swirl to create an optical illusion; and Lisa Simpson’s “Scene from Moby Dick.” (In different episodes of The Simpsons, both Lisa and Marge Simpson are said to be the author of this painting. Sachs chose to go with Lisa because she is his favorite character.)

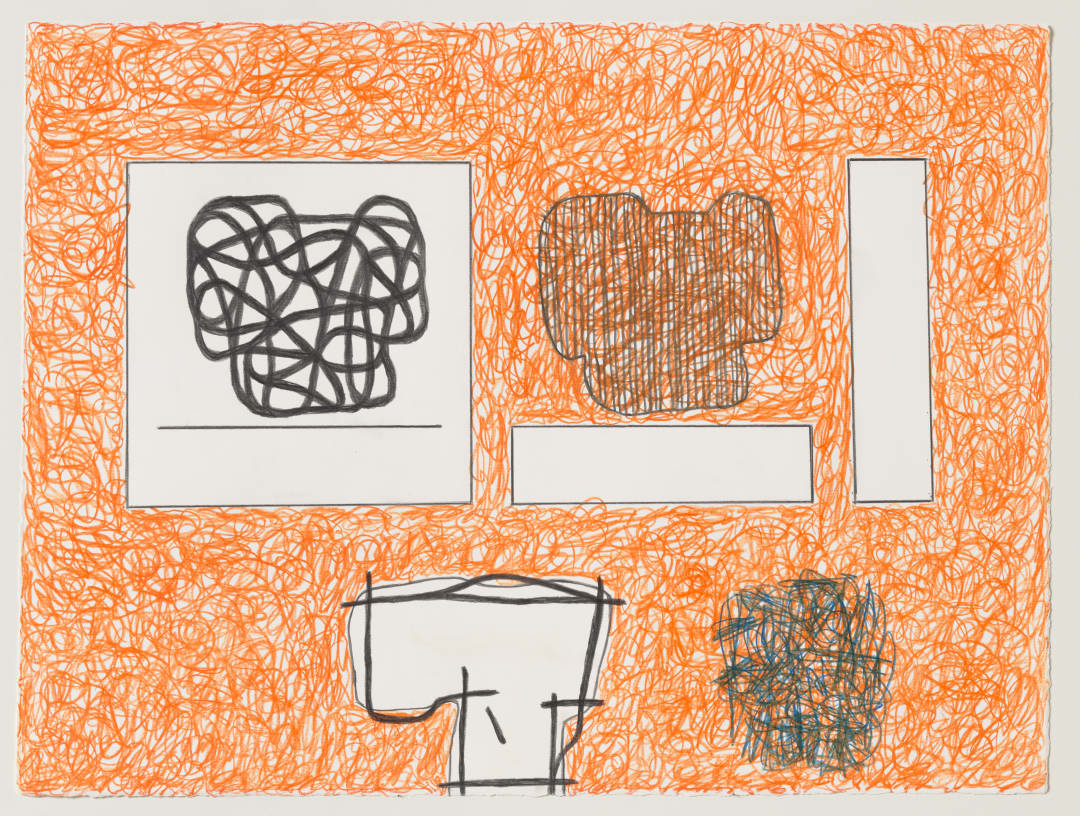

It’s a show about the process of art-making, by an artist who has exhibited an obsession with method since his earliest works. It’s as if, by recreating the works of these three figures, Sachs is trying to answer the question: “What makes a great work of art?” Does true greatness lie in Picasso’s emotional approach, Duchamp’s intellectual approach, or in the pure artistic gesture of a child like Lisa?

Sachs doesn’t consider his versions to be copies, or forgeries, or even studies of the original works. Rather, they are taxonomies, in the way a botanist takes apart a flower, or an anthropologist would study a culture. “I’m looking at art, and at the same time making it mine through my own system.”

JEREMY OLDS: When you mount a show like this, which draws on Picasso and Duchamp artworks and The Simpsons’ intellectual property, do you ever fear the possible legal repercussions?

TOM SACHS: I can’t really worry about stuff like that. I understand why people feel that way. As long as you’re true to yourself and act with integrity, that’s all that matters. Also, we have a tradition in the studio of using preexisting things a lot. There’s parody, and there’s parity. When we showed the Chanel guillotine here in 1998, the lawyers from Chanel were calling up and getting angry. Thaddaeus [Ropac, his gallerist] got on the phone and called Karl Lagerfeld. He said we had to send him a fax. We sent the fax immediately, he saw it, picked up the phone and was laughing – “I love it.” The lawyers were pissed off. But that was the beginning of it and, strategically, it remains the same.

JO: How did the idea of the show emerge, and this trinity of Picasso, Duchamp and Lisa Simpson?

TS: At the heart of it, there’s a conflict between Picasso and Duchamp. I think it’s parallel to the duality of man, the Apollonian and Dionysian spirits, our emotional-intuitive and our intellectual. In spirit, I see myself as more of a Dionysian – an emotional, intuitive artist. In practice and strategy, it’s clearly Duchampian. I’m a conceptually driven, process-oriented artist.

In the end, the men became these two different forces: Picasso, this pure Dionysian figure, painting minotaurs and becoming one of the richest men in the world; and Duchamp’s living on 14th St, giving chess lessons to make a living. When Duchamp died, Picasso’s obituary for Duchamp was, “He was wrong.”

So this conflict is really interesting, but then who am I in all of this? It’s a very subjective body of work by me. My signature’s bigger than Picasso’s. If there’s a conflict between these two figures, then Lisa is, in a way, the artist. She’s doing it for love. She’s 8 years old, she’s painting her heart out. She’s pure of spirit. She is my alter ego. She is who I wish to be.

JO: Why?

TS: I think it’s just her innocence and purity. I’m clearly a grizzled middle-aged dude who’s put up a lot of shelves and made sculptures, but she’s forever 8 years old. She has an innocence that can only be achieved by a fictional character. Like classical mythology: these are ideal figures, no one can really be those things, but that’s what stories are for.

Tom Sachs, Scene from Moby Dick, 2023. Acrylic and krink on canvas. 91,4 x 106,7 x 3,8 cm (36 x 42 x 1,5 in). (TSA 1470). Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery © Tom Sachs.

JO: Do you recall discovering Duchamp, and what you found appealing about his work?

TS: I never was super into Picasso, but when I discovered Duchamp my brain exploded. He was the one who helped me see that there is art in everything. So much of my outlook in life and making art is through his wit.

JO: We see your DIY sensibility in the work in this exhibition – the rough-and-ready painting, the traces on the sculpture. Where does that sensibility come from?

TS: As a child I was forbidden to use tools, because they were too dangerous. But my mom had a tool set in the basement, because she was the handy one, and [my parents] didn’t really stop me. They’d say no, but when I’d go and use them, they didn’t know – or care that much. I taught myself. For many years I was a contractor and did construction jobs. I built so many things myself, so I derive great pleasure from making. That goes into painting – I’m a DIY painter, too.

(...)