Miquel Barceló: “I paint my works in Catalan!” Valérie Duponchelle interviews the artist for the launch of his new book

Entretien - L’artiste de Majorque est devenu une star de la scène internationale dans les années 1980. Après des années où il s’échappait en pays Dogon, au Mali, il navigue entre Paris et son île des Baléares, fuyant les travers du succès.

Miquel Barceló est un homme planté entre terre et mer. Un artiste solaire que son art habite totalement, comme le jeu possède l’enfant, comme l’amour éclaire l’homme heureux. En témoigne son atelier parisien, qui s’est développé organiquement sous les hauts plafonds d’un vieil hôtel du Marais, suite de cellules composées comme des œuvres où sa peinture, sa sculpture, ses collections s’entremêlent, comme dans la Maison-musée Salvador Dalí, à Portlligat, près de Cadaqués, où l’art sert de fil d’Ariane.

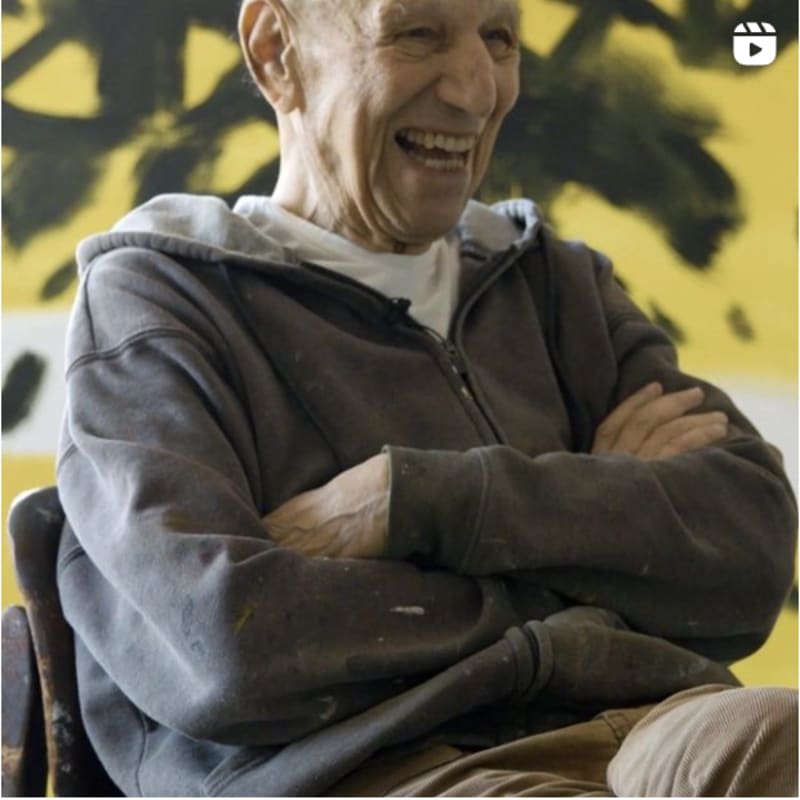

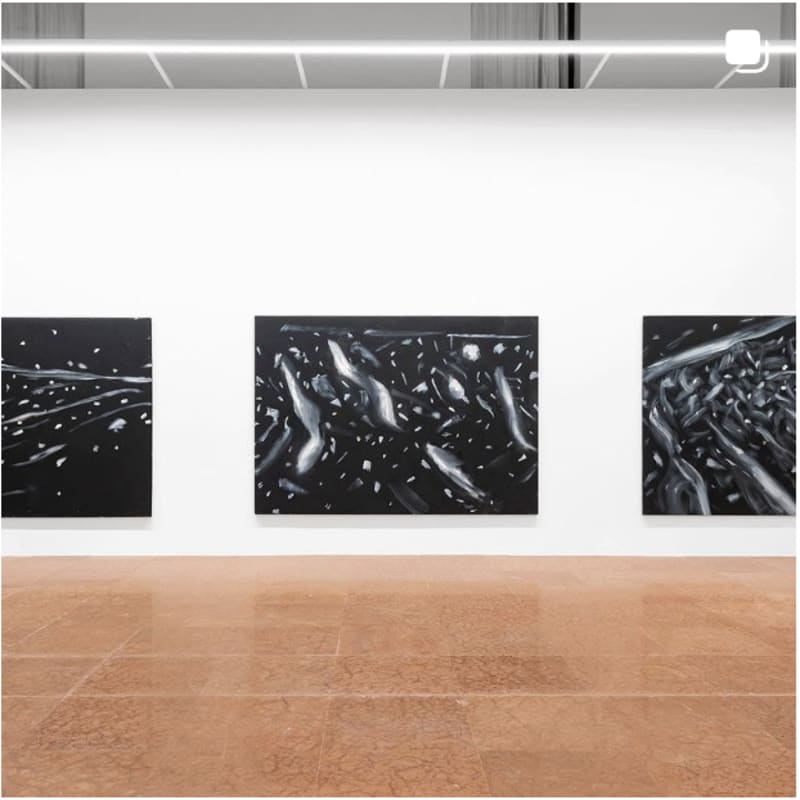

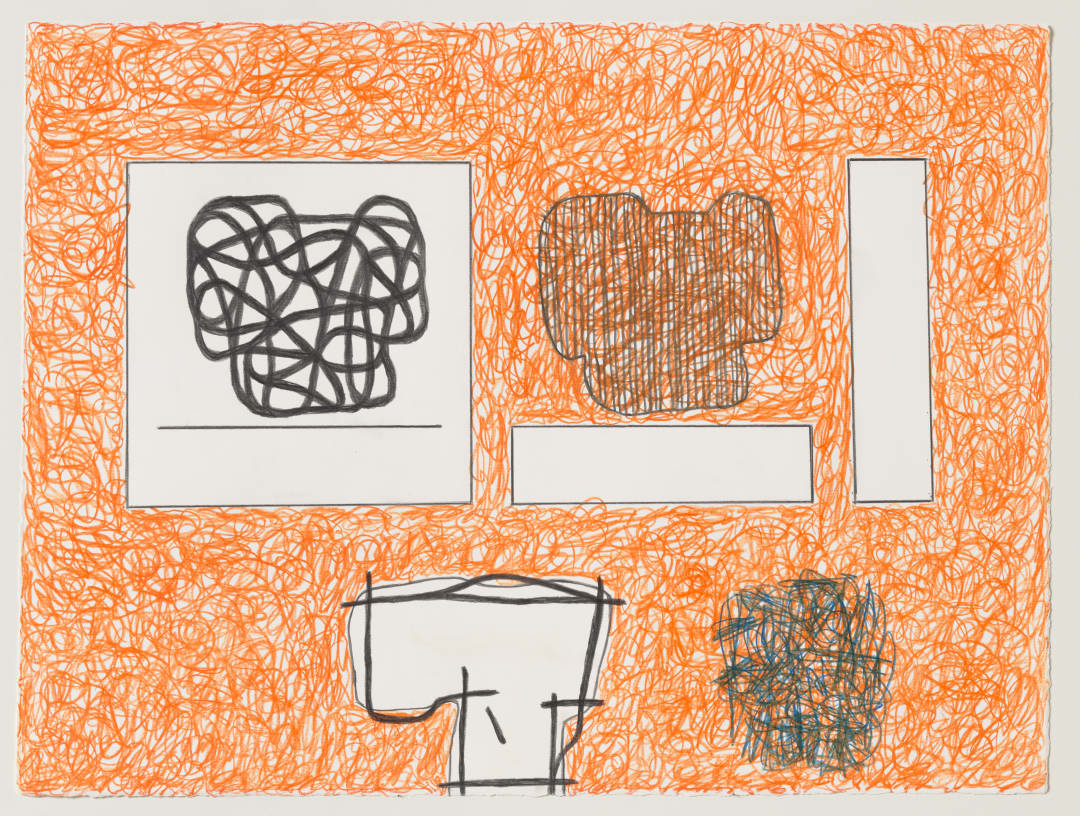

Les espaces se succèdent, dédiés à la gravure, au dessin, aux archives, et chacun est une forme d’autoportrait. Au tréfonds de ce labyrinthe, le peintre, blouse bleue de travail maculée de peinture et cheveux hérissés comme un personnage ahuri de BD, travaille sur sa dernière série. Des peintures en noir sur blanc qui évoquent directement l’art pariétal sur leurs toiles bosselées comme la paroi d’une caverne.

Miquel Barceló est né le 8 janvier 1957 à Felanitx, dans le sud-est de l’île de Majorque. Prodige des années 1980, il fut ardemment soutenu par le marchand suisse Bruno Bischofberger, aujourd’hui 84 ans (qui découvrit Jean-Michel Basquiat), avec lequel il s’entretient toujours régulièrement au téléphone. Il fut longtemps montré à Paris par Yvon Lambert, 88 ans, vétéran de la scène parisienne réputé pour sa rigueur et sa sensibilité profonde à l’art, et désormais par Thaddaeus Ropac, son cadet, l’Autrichien de Paris qui lui a consacré son espace cathédrale de Pantin en 2022.

Miquel BARCELÓ. - J’ai racheté l’atelier sous verrière de l’architecte Étienne Fromanger, frère du peintre pop français Gérard Fromanger, qui se tenait alors au-dessus du mien. Un homme charmant qui m’a expliqué que ces vitrines venaient de Sacha Guitry. Il y gardait ses trésors de collectionneur. Je suis un peu fétichiste, j’y ai mis mes modèles. J’admirais beaucoup ses films. Ce jeune homme qui venait du théâtre a eu l’instinct d’utiliser le cinématographe pour filmer les artistes, écrivains, peintres et sculpteurs. Il ne connaissait même pas le cinématographe et le principe de l’image en mouvement.

Dans ses Mémoires, il raconte qu’il disait à ses sujets: «Vous prenez la pose et, quand c’est bon, je m’arrête!» Dans ses films, il parle sans arrêt, il piaille comme un oiseau, c’est très beau. J’aime beaucoup ses films, le Portrait de Claude Monet, bien sûr, une journée à Giverny, dans l’Eure, en 1915. Il a fait les plus beaux films qui soient sur les artistes. Mais j’aime aussi Le Nouveau Testament, Napoléon, Si Versailles m’était conté. J’aime sa rhétorique, sa grandiloquence, sa diction, sa manière géniale de mettre en scène le grand avec de la pacotille, que tout le monde a copiée ensuite, d’Orson Welles à Godard. Il a fait défiler, le premier, les techniciens et toute l’équipe du générique à l’écran, comme les saluts à la fin d’une pièce au théâtre. C’est un cinéaste très original et, en même temps, c’est très vieille France. L’histoire de l’art, c’est ça, créer un lien avec des gens qu’on n’a pas connus.

Dans votre livre, la référence à Picasso n’arrive que page 123. Pourquoi ?Je n’avais pas réfléchi à ça. Je commence à parler de ma mère qui était peintre, ses amis, c’est de l’histoire de l’art aussi, mon histoire personnelle. Tout est histoire de l’art, on prend ce qui est à côté de vous. Toutes les sources fusionnent pour créer un artiste. Cézanne est venu plus tard. La deuxième fois que j’ai séjourné, étudiant, à Paris, j’ai voulu aller voir toutes les adresses de Picasso, je les ai trouvées dans les livres. Je suis allé à Montmartre, rue Gabrielle, place Ravignan, à Montparnasse, rue La Boétie, rue des Grands-Augustins, l’endroit qui m’a le plus marqué. Je n’entrais pas, je les regardais du dehors. Je n’ai jamais cessé d’admirer Picasso.

Vous tenez un journal ?

Non, pas un journal proprement dit, mais beaucoup de carnets de dessins et d’esquisses, parfois des notes, que j’écris chaque jour. Grâce à ma mère, je les garde depuis l’enfance et j’ai la collection complète, classée, ici, dans mon atelier. Je les regarde et j’y puise des idées. Pour ce livre, je ne voulais pas faire le fac-similé d’un carnet, je trouve ça un peu creux. Je suis parti avec certains de mes carnets au Japon faire des céramiques dans les montagnes au nord de Kyoto. J’ai mélangé tout ça. Je ne suis pas un écrivain, le français n’est pas ma langue maternelle, c’est ma langue de lecture. Je m’y exprime comme si j’écrivais en latin savant. Cela me donne une liberté que je n’aurais pas en catalan ni en espagnol, où je suis trop impliqué. Mes tableaux, je les peins en catalan ! (Rires.)

Ma peinture n’a rien de littéraire, mais j’ai besoin de la lecture, processus actif et clé de l’imaginaire des autres qui vous donne accès à votre imaginaire

Vous avez été un lecteur précoce - 3 ans ! - et vous avez dévoré, très tôt, les livres de la bibliothèque de Felanitx. Vous aimiez Rimbaud, Baudelaire, Nerval. Mais pas Verlaine, jusqu’à votre vie à Paris…

Je suis un bon lecteur, depuis tout jeune. J’ai établi la liste de mes auteurs par ordre de lecture, d’El Quijote, que je lisais à l’école primaire et dont j’avais mémorisé les premières pages comme un singe, puis Dumas, Verne, Kerouac, Borges, Rimbaud, Kafka jusqu’à santa Teresa et Lautréamont. Je trouve que lecture et peinture sont de bons vases communicants. Ni le cinéma ni l’image n’ont cette vertu. La lecture crée cet espace où l’on se vide et d’où peut naître la peinture. Ma peinture n’a rien de littéraire, mais j’ai besoin de la lecture, processus actif et clé de l’imaginaire des autres qui vous donne accès à votre imaginaire. C’est toujours un bonheur. Je lis beaucoup, de tout, des choses mauvaises que j’abandonne ou des auteurs que je reprends. Borges dit qu’il n’y a rien de plus émouvant que les meilleurs vers d’un mauvais poète. Je trouve toujours des choses bien, tout le temps, en cherchant dans les librairies. Avec les ans, j’ai constitué un petit comité d’amis qui me donnent des pistes en poésie, en prose, en espagnol, en français. Dès que j’aime un livre, je le fais lire à tout mon réseau.

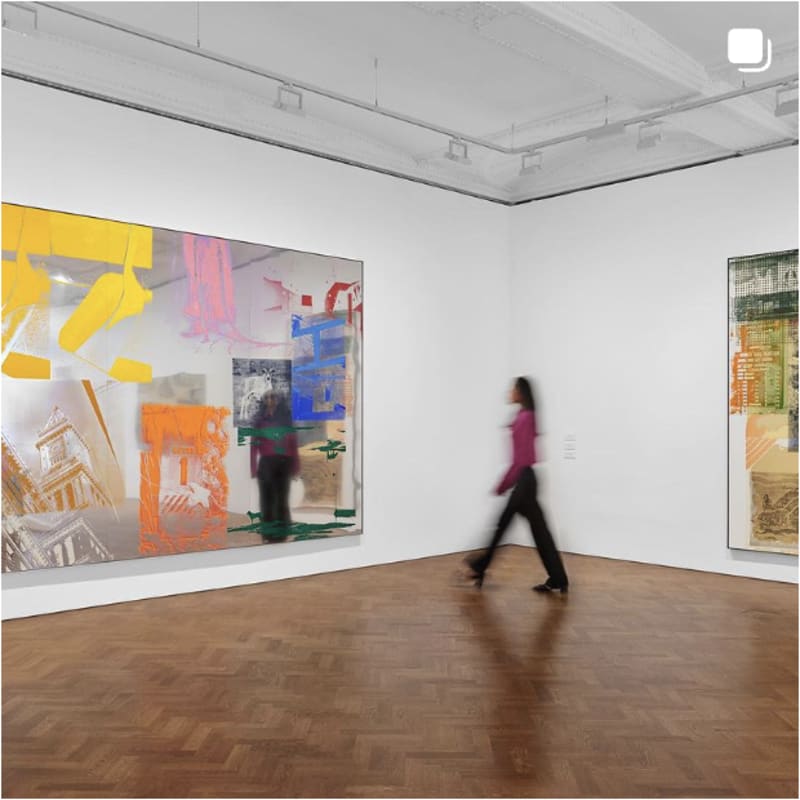

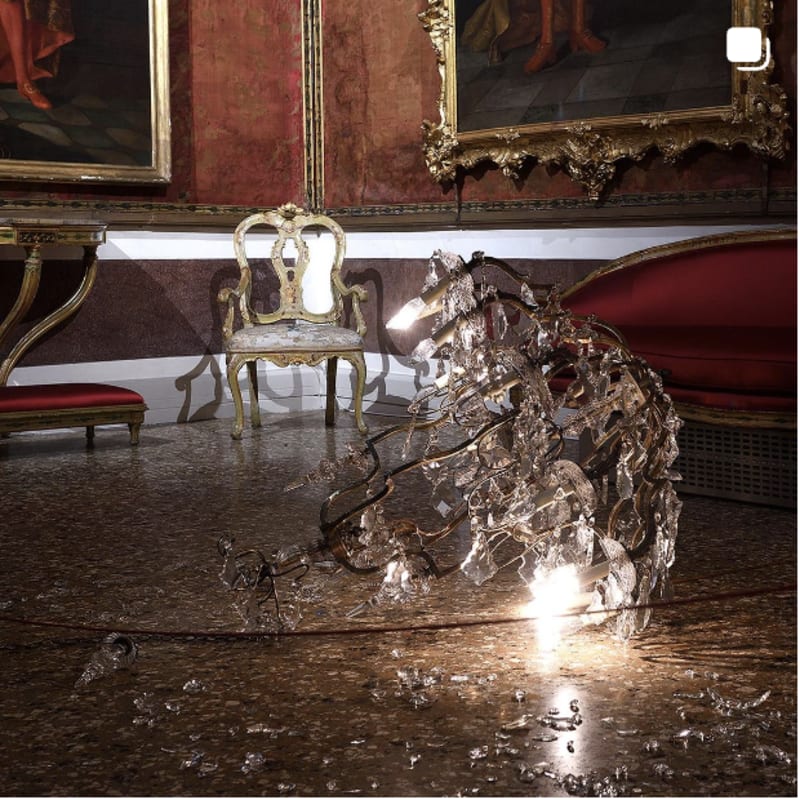

L’atelier parisien de Miquel Barceló, qui s’est développé organiquement sous les hauts plafonds d’un vieil hôtel du Marais François. BOUCHON / François Bouchon / Le Figaro

L’atelier parisien de Miquel Barceló, qui s’est développé organiquement sous les hauts plafonds d’un vieil hôtel du Marais François. BOUCHON / François Bouchon / Le Figaro

Quelle est l’importance de Majorque dans votre œuvre ?

Je suis l’aîné de trois. Je suis né au XXe siècle, mais, si j’étais né au XIXe, cela aurait été exactement pareil. J’ai connu Majorque, île agricole avec ses charrettes et ses pêcheurs avant l’arrivée des touristes… Et aussi l’Europe qui a attribué une fonction à chaque pays et nous a affectés, comme tous les pays du Sud, un rôle de service. L’Europe ne veut pas d’agriculture sur cette île désormais destinée à construire des maisons d’été pour de riches Suédois. Comme toute la Méditerranée Majorque a perdu en beauté au nom du progrès et du confort. Le patrimoine populaire, la mémoire, ont été sacrifiés. Je suis un artiste postmoderne, j’ai vécu cela dans mon corps.

Du fait de la poussée islamiste, vous n’allez plus en pays dogon, au Mali, où vous avez fui les pièges du succès. Un rêve de voyage ?

Je rêve d’aller sur les traces de Constantin Brancusi en Roumanie et de retrouver un paysage de polyculture et de meules de foin à l’ancienne, comme chez Monet. Tous ceux qui y sont allés sont revenus fascinés.

Translation :

Interview - The Mallorcan artist became an international star in the 1980s. After years of escaping to the Dogon country in Mali, he now travels between Paris and his island in the Balearics, escaping the pitfalls of success.

Miquel Barceló is a man settled between land and sea. He is a sunny artist whose art inhabits him completely, just as play possesses a child and love illuminates a happy man. Miquel Barcelo is a man settled between land and sea. He is a sunny artist whose art inhabits him completely, just as play possesses a child and love illuminates a happy man. This is reflected in his Paris studio, which has developed organically under the high ceilings of an old hotel in the Marais district, a series of cells composed like works of art where his painting, sculpture and collections intermingle, as in the Salvador Dalí House-Museum in Portlligat, near Cadaqués, where art serves as an Ariadne's Thread.

A succession of rooms are dedicated to engraving, drawing and archives, and each is a kind of self-portrait. In the depths of this labyrinth, the painter, wearing a blue smock smeared with paint and his hair bristling like a bewildered comic-book character, is working on his latest series. His black and white paintings recall parietal art, with their dented canvases like the walls of a cave.

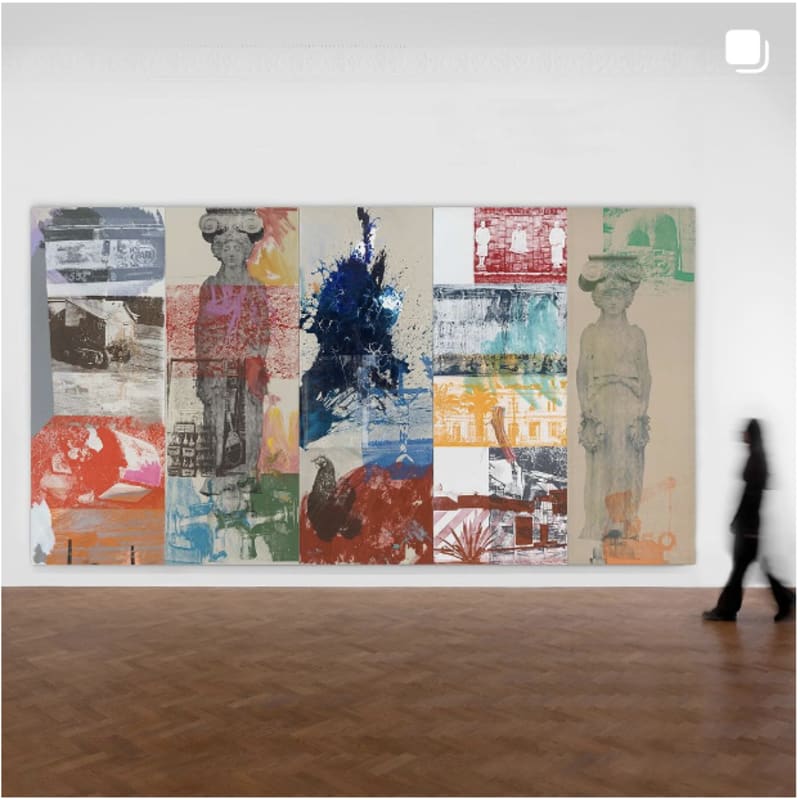

Miquel Barceló was born on 8 January 1957 in Felanitx, in the South-East of the Mallorca Island. A prodigy of the 1980s, he was ardently supported by the Swiss art dealer Bruno Bischofberger, now 84 (who discovered Jean-Michel Basquiat), with whom he still has regular telephone conversations. For a long time he was shown in Paris by Yvon Lambert, 88, a veteran of the Paris art scene renowned for his rigour and deep sensitivity to art, and now by Thaddaeus Ropac, his younger, the Austrian from Paris who has dedicated his cathedral space in Pantin to him in 2022.

For the first time, he tells his own story, with stories as fresh as the dawn and drawings bursting from the pages in De la vida mía (Mercure de France). Meet the man who magnificently decorated the Sant Pere chapel in Palma de Mallorca cathedral in 2007. In 2016, he also transformed the long glass corridor of the BnF - François-Mitterrand into a striking fresco, hand-painted in raw clay.

LE FIGARO. - You live with Sacha Guitry's bookshelves, which you have transformed into showcases for your collections. Why Guitry?

Miquel BARCELÓ. - I bought the studio under the glass roof of the architect Étienne Fromanger, brother of the French pop painter Gérard Fromanger, whose studio stood above mine at the time. A charming man, he explained to me that these windows came from Sacha Guitry. He used to keep his collector's treasures in here. I'm a bit of a fetishist, so I put my models there. I particularly admired his films. This young man who came from the world of theatre had the instinct to use the cinematograph to film artists, writers, painters and sculptors. He didn't even know cinematography and the principle of the moving image.

In his Memoirs, he recounts how he used to say to his subjects: "You strike a pose and, when it's good, I stop!" In his films, he talks non-stop, he chirps like a bird, it's very beautiful. I love his films, the Portrait of Claude Monet, of course, a day in Giverny, in the Eure, in 1915. He made some of the most beautiful films about artists. But I also love The New Testament, Napoléon, Royal Affairs in Versailles. I love his rhetoric, his grandiloquence, his diction, his brilliant way of staging the great with the shoddy, which everyone copied afterwards, from Orson Welles to Godard. He was the first to parade the technicians and the whole crew from the credits to the screen, like the salutes at the end of a play in the theatre. He's a very original filmmaker and, at the same time, very old-fashioned. That's what art history is all about, creating a link with people you never knew.

In your book, the reference to Picasso only appears on page 123. Why do you think that is?

I hadn't thought about that. I start talking about my mother who was a painter, her friends, which is art history too, my personal history. Everything is art history, you take what's next to you. All the sources merge to create an artist. Cézanne came later. The second time I stayed in Paris as a student, I wanted to go and see all Picasso's addresses that I'd found in books. I went to Montmartre, rue Gabrielle, place Ravignan, Montparnasse, rue La Boétie, rue des Grands-Augustins, the place that made the biggest impact on me. I wouldn't go in, I'd watch them from outside. I've never stopped admiring Picasso.

Do you keep a diary?

Well, not a diary as such, but a lot of notebooks of drawings and sketches, sometimes notes, that I write down every day. Thanks to my mother, I've kept them since I was a child and I've got the whole collection filed away here in my studio. I look at them and draw ideas from them. For this book, I didn't want to do a facsimile of a notebook - I find that a bit hollow. I took some of my notebooks to Japan to make ceramics in the mountains north of Kyoto. I've mixed all that up. I'm not a writer, French isn't my mother tongue, it's my reading language. I express myself as if I were writing in erudite Latin. It gives me a freedom that I wouldn't have in Catalan or Spanish, where I'm too involved. I paint my pictures in Catalan!

There's nothing literary about my painting, but I do need to read, the active process and the key to other people's imaginations that gives you access to your own.

You were a precocious reader - 3 years old! - and you devoured the books from the Felanitx library at a very early age. You loved Rimbaud, Baudelaire and Nerval. However, not Verlaine, not until you moved to Paris...

I've been a good reader since I was very young. I've drawn up a list of my authors in order of reading, from El Quijote, which I read at primary school and memorised the first few pages like a monkey, then Dumas, Verne, Kerouac, Borges, Rimbaud, Kafka to Santa Teresa and Lautréamont. I find that reading and painting are good communicating vessels. Neither film nor images have this virtue. Reading creates a space where you can empty yourself and from which painting can emerge. There's nothing literary about my painting, but I do need to read, the active process and the key to other people's imaginations that gives you access to your own. It's always a pleasure. I read a lot, everything, bad things that I abandon or authors that I take up again. Borges says that there is nothing more moving than the best lines of a bad poet. I always find good things, all the time, by looking in bookshops. Over the years, I've built up a little committee of friends who give me advice on poetry, prose, Spanish and French. As soon as I like a book, I get my whole network to read it.

How important is Mallorca in your work?

I'm the eldest of three. I was born in the 20th century, but if I'd been born in the 19th it would have been exactly the same. I knew Majorca as an agricultural island with its carts and fishermen before the arrival of tourists... And also Europe, which has assigned a function to each country and has assigned us, like all the countries of the South, a service role. Europe does not want agriculture on this island, which is now destined to build summer homes for wealthy Swedes. Like the whole of the Mediterranean, Mallorca has lost its beauty in the name of progress and comfort. The island's popular heritage and memory have been sacrificed. I'm a postmodern artist, I've experienced this in my body.

Because of the Islamist upsurge, you are no longer going to the Dogon country in Mali, where you fled the traps of success. Do you have a dream destination?

I dream of following in the footsteps of Constantin Brancusi in Romania and rediscovering a landscape of mixed farming and old-fashioned haystacks, as in Monet's work. Everyone who's been there has come back fascinated.