By Following His Instructions, You Too Can Become an Erwin Wurm Artwork The Austrian conceptual artist discusses his relationship to sculpture, the human body, and mundane objects in his current exhibition “Hot,” at the SCAD Museum of Art in Savannah, Georgia.

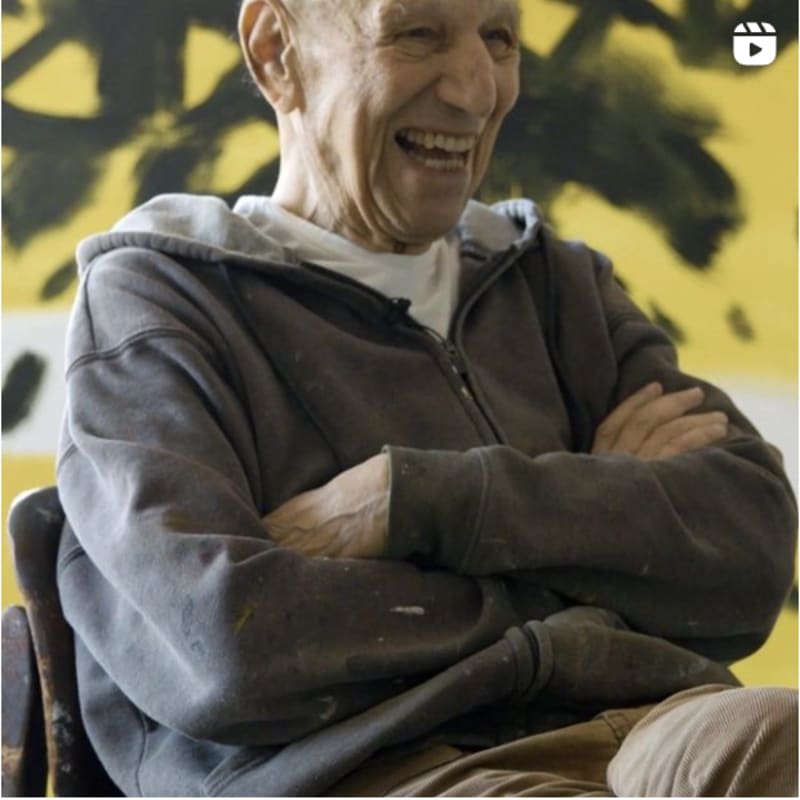

When MTV was at its peak, Erwin Wurm received a phone call from famed music video director Mark Romanek, who asked to use the Austrian artist’s work in a video for the Red Hot Chili Peppers’s 2002 bop “Can’t Stop.” “I didn’t know the Red Hot Chili Peppers [back then], I have to confess,” Wurm said in a recent conversation with the SCAD Museum of Art’s chief curator Daniel S. Palmer and curator Ben Tollefson. Despite his lack of familiarity with the band’s output, Wurm took the opportunity to collaborate with Romanek and became one of the first artists to get credited on MTV, which, according to Palmer, was “a legendary moment.”

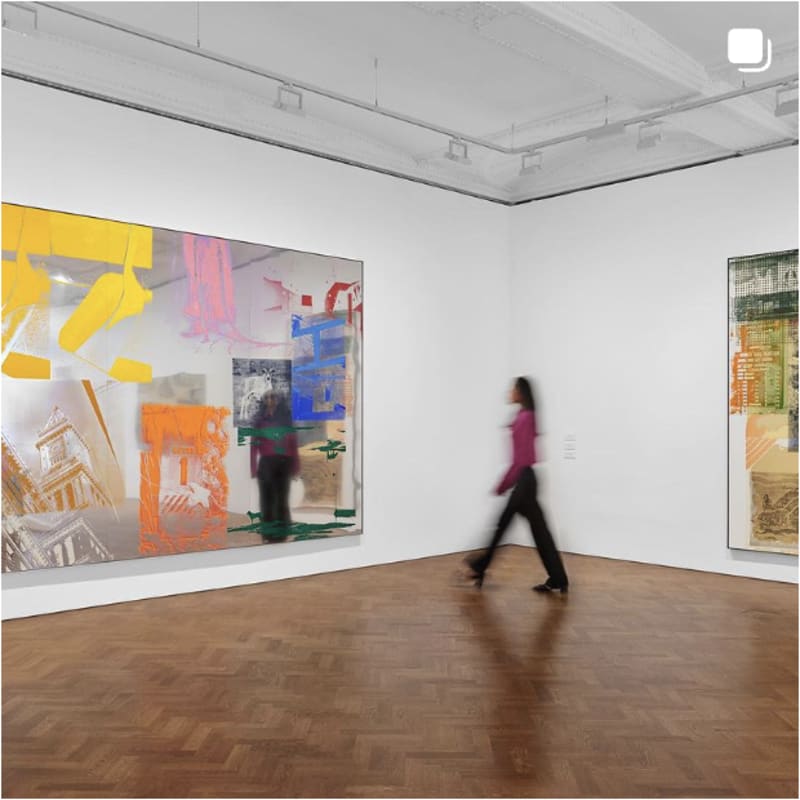

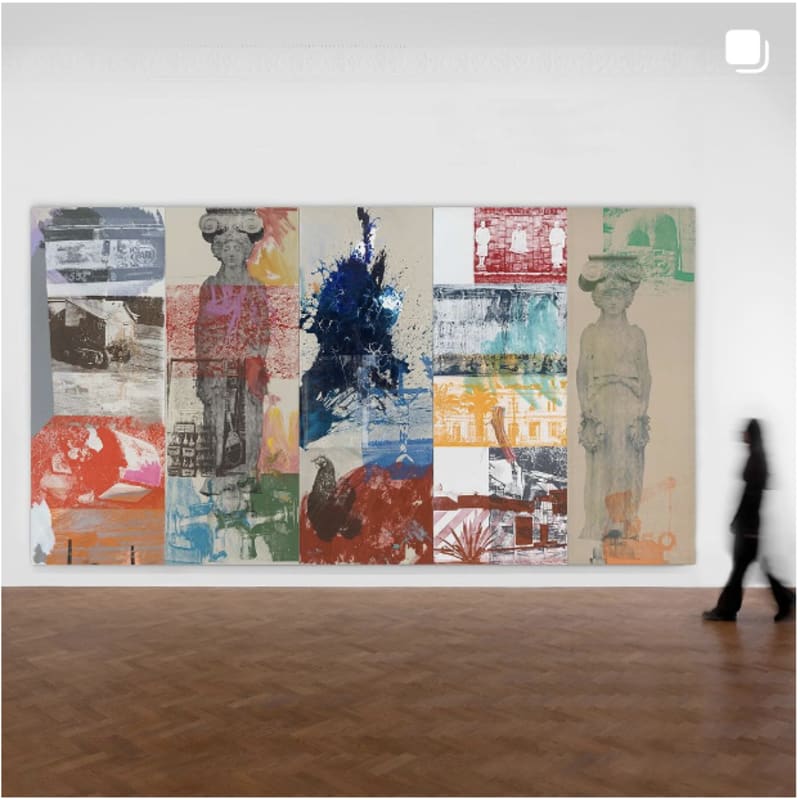

Over two decades later, Wurm is now a household name for art lovers and pop culture devotees around the world. Earlier this month, he sat down with Palmer and Tollefson for an artist’s talk at the SCAD Museum of Art, where his exhibition “Hot” is currently on view through Jan. 15, 2024. The show takes place in two of the museum’s main galleries including the André Leon Talley Gallery.

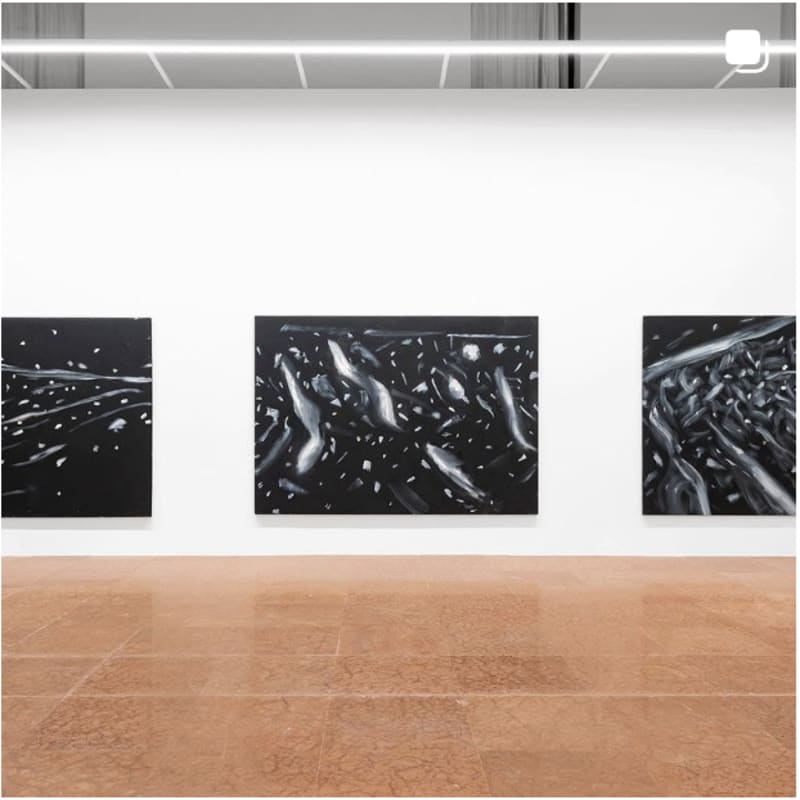

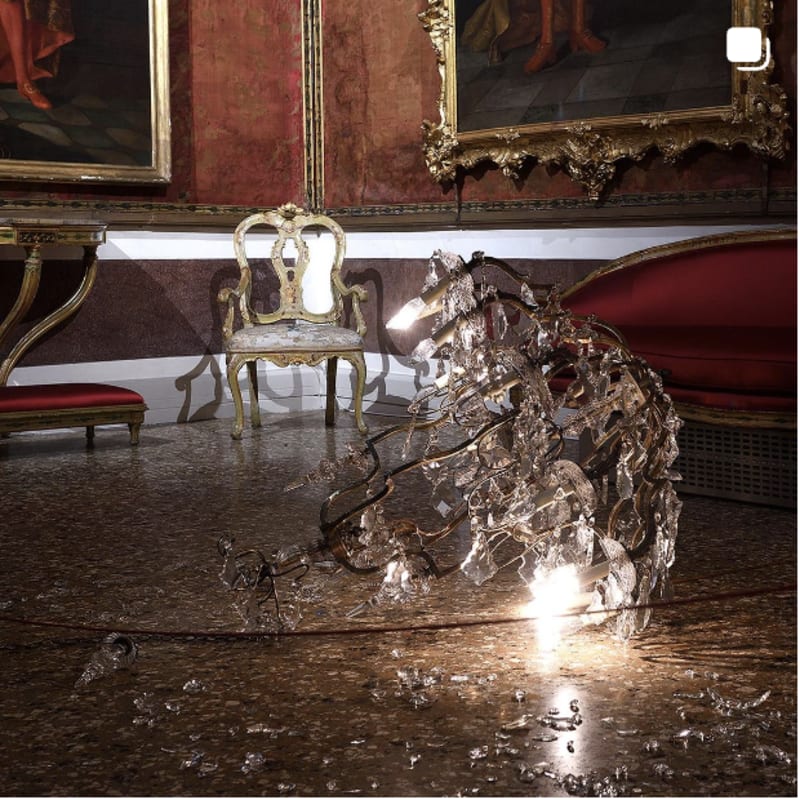

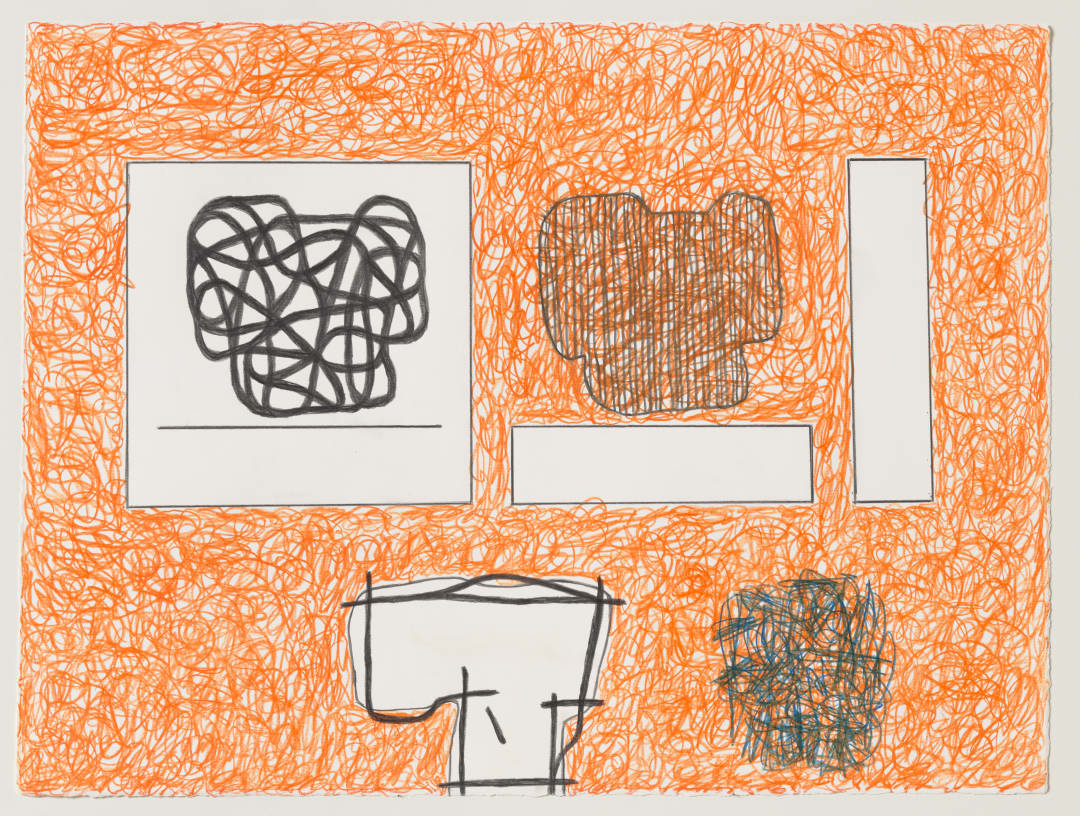

In the former, Wurm showcases his experimental works in various mediums—including the “One Minute Sculptures” series that inspired the Red Hot Chili Peppers music video. The latter space focuses on the artist’s intersection with the world of fashion, featuring photographs and sculptures that turn designer garments into warped interpretations of the human body.

Below, Wurm’s conversation with the show’s curatorial duo has been exclusively shared with CULTURED. The beloved artist touches on his vision of sculpture, why he’s used himself as a model, and turning viewers into works of art.

Daniel S. Palmer: The relationship of the human body and everyday objects is something that's been at the core of your work for a long time.

Erwin Wurm: I wanted to become a painter, and when I tried to apply to an art school, they didn't accept me in the painting class. They put me in a sculpture class. This was frustrating. After a while, I accepted it and started to take it as a challenge. From that point on, I started to ask questions about what sculpture is. I tried to combine three things: the body, the social aspect, and the sculpture issue. As an artist, I relate to the time [that] we live in. How can we live in a world with seven billion universes? We all have to get together in a way to make it possible to live together in peace.

Ben Tollefson: Speaking of your time in art school—wanting to join the painting department, and eventually going into sculpture—it makes me think about your “One Minute Sculptures.” They put you on the map as an artist. Can you talk about how they came to be?