Sean Scully At Houghton Hall

BY JAVIER MOLINS

Just like in most English manor houses, the journey to Houghton Hall unfolds along a lengthy path, meandering through vast gardens that boast a remarkable feature: herds of deer gracefully roam the grounds. Built in 1720 in the Anglo-Palladian style for Britain’s Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole, this magnificent residence is now owned by David Cholmondeley, the seventh Marquess of Cholmondeley.

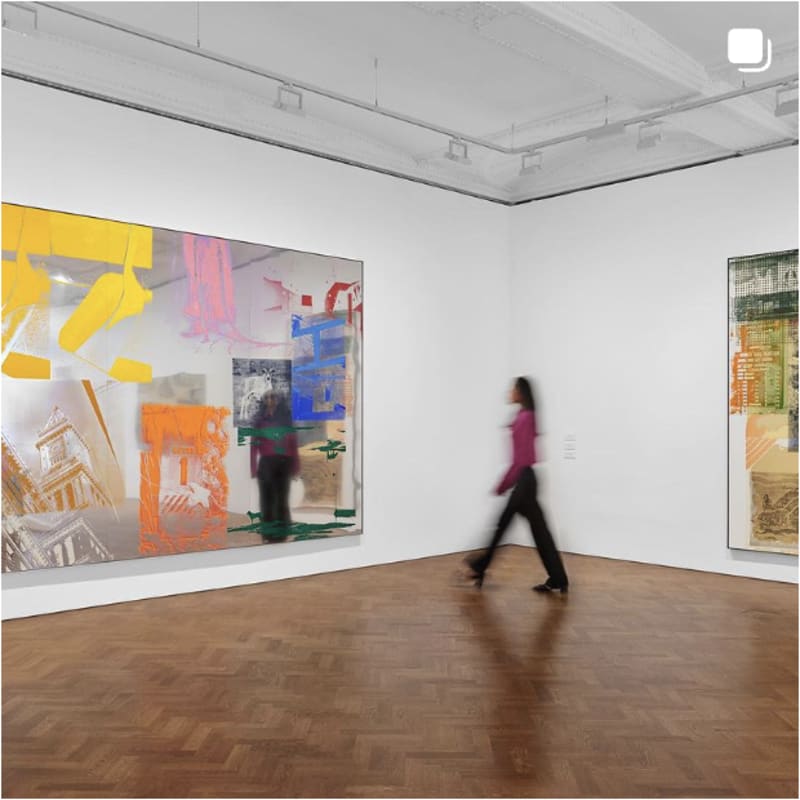

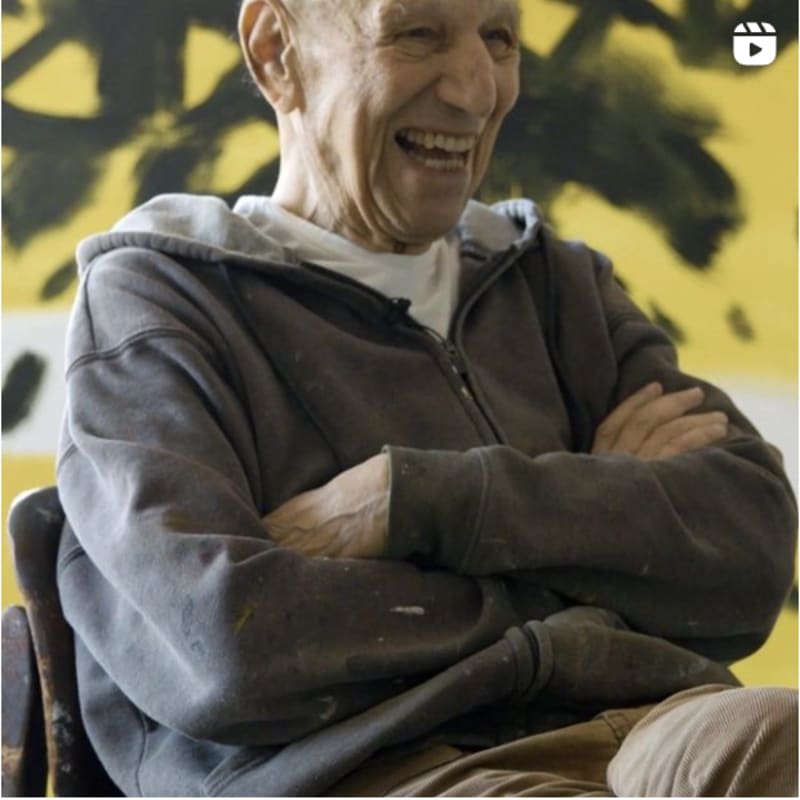

However, neither of these historical figures takes center stage during a visit to this estate. The true protagonist is Sean Scully, acclaimed as the foremost abstract artist of our time, who presents his masterpieces within the domains of a family whose origins bear little resemblance to his own humble beginnings. A staff member graciously guides us to the designated parking area, leading us towards the entrance where we are warmly greeted with a glass of champagne. Once we step foot into the vast gardens, I catch sight of Sean Scully himself, seated on a bench, quietly observing how the guests at the inauguration interact with his sculptures scattered throughout the labyrinthine corners of this stately home.

Although Sean has resided in New York for several decades, he plans to relocate to London come September. And his return to England could not have been more grandiose. Just three days ago, he unveiled a permanent sculpture in Hanover Square, one of London’s most central squares. Now, until October 29, his works are on display at Houghton Hall, a venue that has previously showcased esteemed British artists such as Tony Cragg and Anish Kapoor.

However, Sean’s beginnings in London were far from easy. “I was born in Dublin, where we lived as vagabonds with no place to call home. We moved to the worst suburbs in London. By the time I turned five, we had already lived in over ten different houses, instilling in me a strong sense of instability,” he confides, as he gazes from that very bench upon the British high society and a multitude of international collectors who have flocked to admire works worth over a million dollars. Yet, Sean never loses sight of his humble origins: “In England, you can attend evening classes and, if you are ready to work hard, you can change your life. Every school in England offers free evening classes. We should be proud of that. I studied diligently in night school and eventually gained admission to the Croydon School of Art.”

Scully hails from a modest family, but one deeply rooted in a generational sense of morality. His grandfather was sentenced to death for deserting the British army. “He was scheduled to be executed at seven in the morning but chose to hang himself in his cell.” As if that were not enough, his father also deserted during World War II, leading to his confinement in a military prison. “I come from a family accustomed to dying for their principles,” he remarks.

Many visitors to the exhibition, including the director of the National Gallery in London, Gabriele Finaldi, may not be privy to the intricacies of Scully’s life story. However, they undoubtedly appreciate an oeuvre that has rightfully claimed a prominent position in the annals of 21st-century art. Few contemporary artists can boast of having exhibited in esteemed museums such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Albertina Museum in Vienna, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

It was a long and grueling journey full of hard work because, as Scully himself explains, “I am a fucking fighter.” Sean Scully belonged to a generation of young working-class individuals in England, much like actor Michael Caine, model Twiggy, and the Beatles, who yearned to change the status quo in a rigidly constrained era that was gradually fading into the past. Even then, Scully knew that he did not want a conventional, predictable, and mundane life—and art became a refuge for him. In fact, at the age of 17, while working at the Victoria Palace Hotel, he would sneak away almost every day to behold Vincent van Gogh’s painting titled Van Gogh’s Chair (1888). An old wicker chair that already exhibited those distinct lines that would later become characteristic of Scully’s own works.

In 1973, Scully held his first solo exhibition at London’s Rowan Gallery. The show was a resounding success, with all of his works being sold. London during that time, as Scully himself describes it, was “a city teeming with temptations, reasons not to work, irony, and where there was a party every week.”

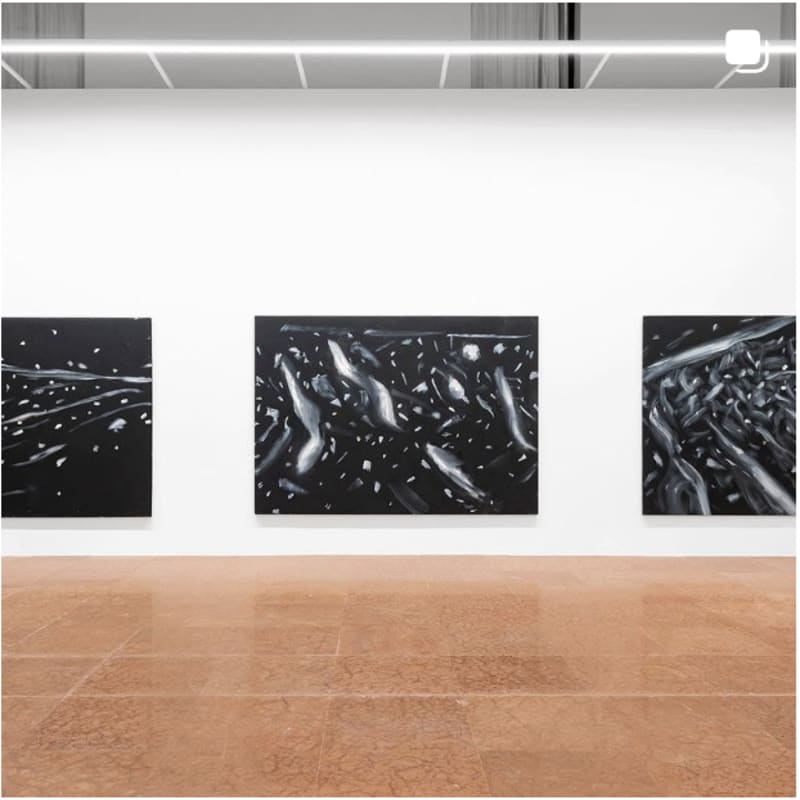

In 1975, Sean Scully made the decision to move to New York. In 1977, he held his first solo exhibition in the city at the Duffy-Gibbs Gallery, and a year later, he began teaching at Princeton University. When Scully arrived in New York, his work took on a highly minimalist approach. As he explains, “The color was reduced right down. What I did when I went there was really to strip myself right down to nothing, basically - as far down as I could go without having a thing. I didn’t want to take anything with me. It was really an extreme action - personally quite dangerous, I think - and it was something I did with my entire being; there was a real sense of existential danger when I moved to New York.”

However, every artist strives to find their own unique voice, and there comes a moment when they decide to break free from minimalism. “For five years, I was creating extremely minimalistic paintings. I was a highly respected member of the New York art community. But in 1980, I broke away from minimalism. This decision led to outrage from my artist friends. People would look at my new works and ask, ‘What the hell is this?’ Suddenly, I introduced emotion, color, relationships, and descriptive titles such as Empty Heart, The Bather, and Adoration—titles that were not permitted in the puritanism of minimalism.” Misunderstanding and even contempt from one’s contemporaries are inherent to artists who attempt to break free from established norms and seek new paths. After all, it was the mediocre painter Giorgio Vasari who said of Tintoretto, “Had he not abandoned the beaten track but rather followed the beautiful style of his predecessors, he would have become one of the greatest painters seen in Venice.”

Scully smiles upon hearing Vasari’s words, for he surely must have encountered similar sentiments when he decided to abandon minimalism in favor of a type of painting that restored emotion to abstraction, which had become so confined by the limits of minimalism. We stroll through the endless gardens of this stately home, originally designed by Colen Campbell and James Gibbs, and encounter a sculpture composed of a tower of marble discs—a form that repeats in another piece crafted from stone. Scully explains, “These works are inspired by the stacks of coins my father used to make at home because every coin, no matter how small, was welcomed.”

Indeed, Scully not only carries over the iconography of his paintings into sculpture, a recent addition to his repertoire, but also infuses his personal experiences into his creations. Every artwork he produces arises from reality—from his own experiences, travels, readings, and, ultimately, from his own life.

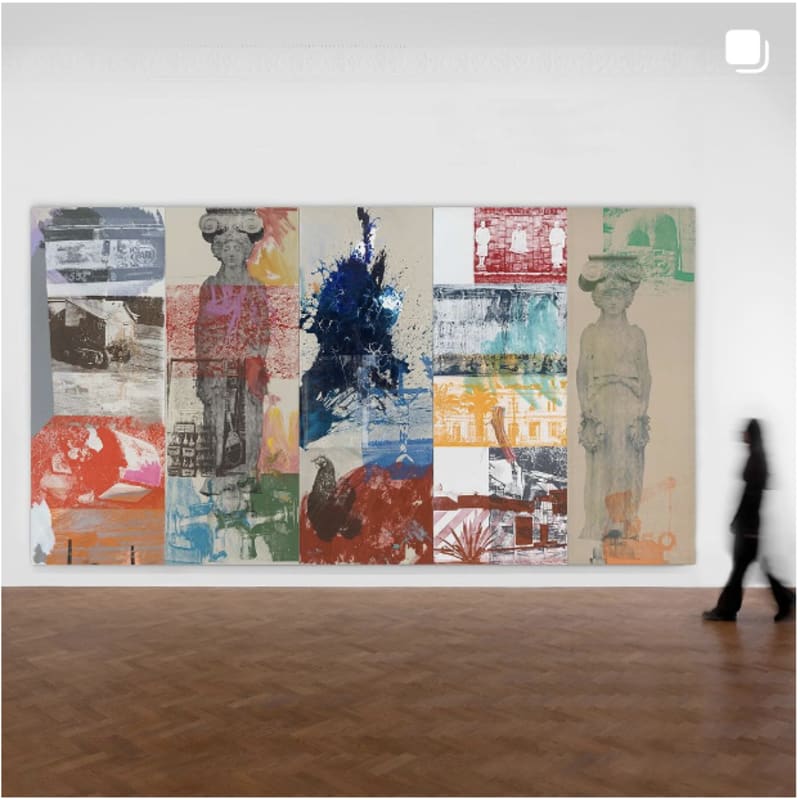

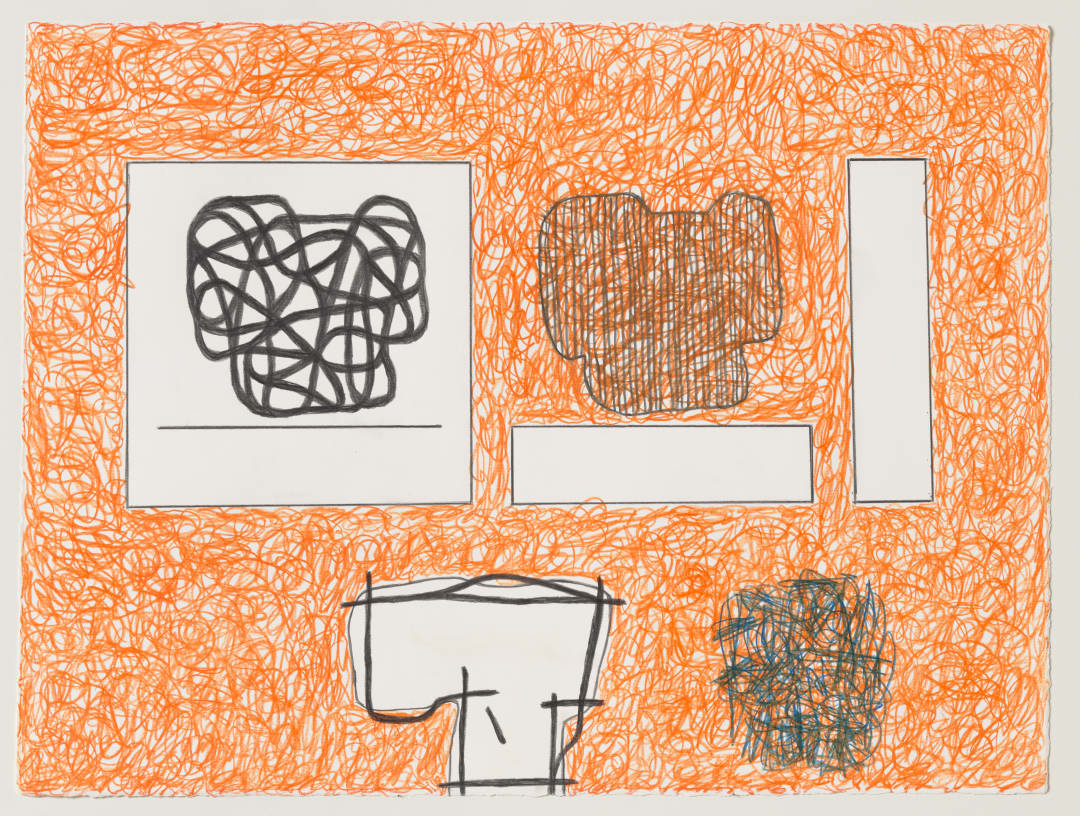

Guests venture into the grandeur of this stately home, which has hosted celebrated friends of its owner, such as model Kate Moss, who is the godmother to one of his daughters. In one of its most noble salons, we can behold two of Scully’s most recent paintings. These are his renowned Landlines—paintings adorned with horizontal stripes yet with the unique addition of small square inserts, reminiscent of his Wall of Light series, characterized by both vertical and horizontal stripes. These works encapsulate a significant portion of Scully’s artistic production. On one hand, we have the Landlines, evoking the lines of the horizon. As the artist himself explains, “I used to constantly gaze at the horizon, all the way to the end of the sea, where it meets the sky, contemplating how the sky presses against the sea, how that line is painted. One day, I stood facing Ireland, on the edge of Aran Island, gazing into the horizon. My next stop: the United States. Standing in the Old World, gazing and contemplating my new life in the New World, as so many others had done before me... gazing and awaiting my arrival in America. I think of the land, the sea, and the sky. And they always establish this brutal connection. I try to paint it, to paint that sense of elemental communion between the sea and the land, the sky and the land, blocks joined together on one side, stacked in horizontal lines of infinite beginnings and endings, to paint how the world’s blocks embrace each other, touch, their weight, their air, their color, and the gentle uncertain space between them.”

On the other hand, we have the Wall of Light series, which originated during a trip to Mexico. “In Mexico, while exploring the ruins, I created a small watercolor where I wrote ‘Wall of Light,’ I don’t know why. Thirteen years later, I began making my Wall of Light paintings,” he explains. He also drew inspiration from the geometric forms of ruins in Mexico such as Chichén Itzá and Uxmal—pyramids constructed with rectangular stone blocks, strikingly similar to those that would later appear in his artwork. In fact, these works from the Wall of Light series function as true architectural walls.

Finally, we have the inserts—artworks that Scully incorporates within others, acting as windows. “Windows are a tremendous metaphor for me. In windows, what I call the dual experience takes place: being inside and looking outside, being outside and looking inside. It’s a great human invention. In fact, the word ‘window’ in English also means ‘opportunity.’”

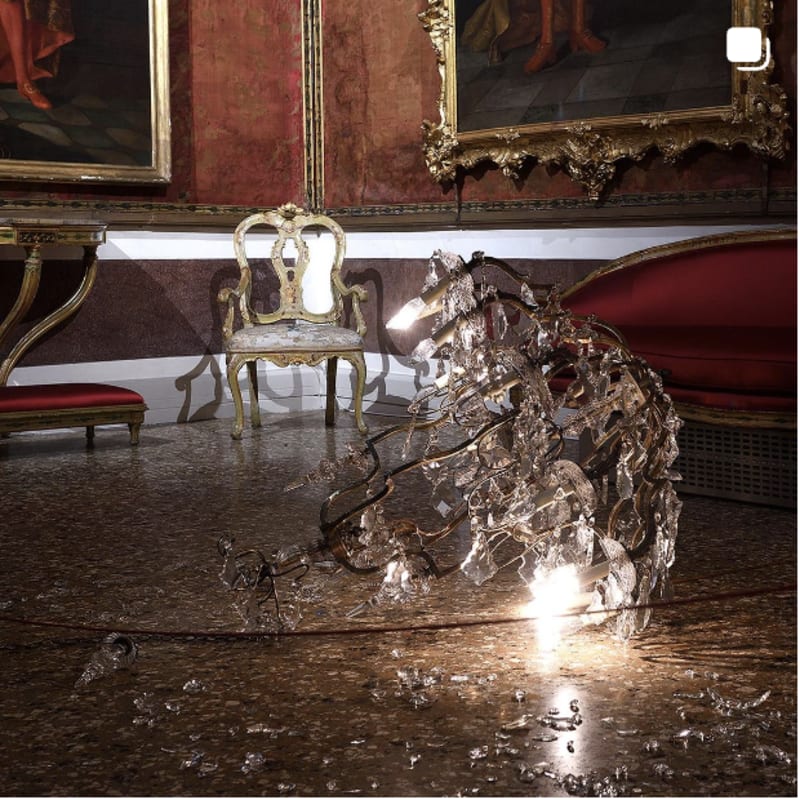

Scully makes this statement in front of the enormous windows in the salons of Houghton Hall, allowing light to bathe one of his sculptures made of Murano glass, displaying an array of colors resembling the entire rainbow. At that moment, a young woman guides us towards the dining room, where the seventh Marquess of Cholmondeley is hosting a meal for the guests. These types of events are not always comfortable for Scully, but he recognizes that they are part of the experience of exhibiting in places like this.

However, there is one exhibition that this artist will never forget—a dialogue between his own work and that of Turner, held at the National Gallery in London in 2019. It took place just a few meters away from the room that houses Van Gogh’s chair, which Scully used to visit almost daily when he was 17 years old and working at the Victoria Palace Hotel. Sometimes, dreams do indeed come true.