With Ritual, Tom Sachs reflects on consumerism while dealing with the history of New York City, and American culture at large. Influenced by the subcultures of an urban metropolis like New York, specifically the phenomenon of corner stores, the artist has replicated commonplace industrial objects using everyday materials, including plywood, cardboard, resin, tape and paint. Exhibited on bespoke pedestals referencing the art of Constantin Brancusi, each work demonstrates the comprehensive spectrum of Sachs' distinctive practice as well as his ability to convey different narratives through formal qualities. In line with the bricolage aesthetic that has gained him a unique position in the field of contemporary sculpture, these works bear the traces of their making, becoming vehicles for a reflection on the creation of value and human labour.

As I create, I meditate, and the lust of acquiring a product is replaced by the love of making it. — Tom Sachs

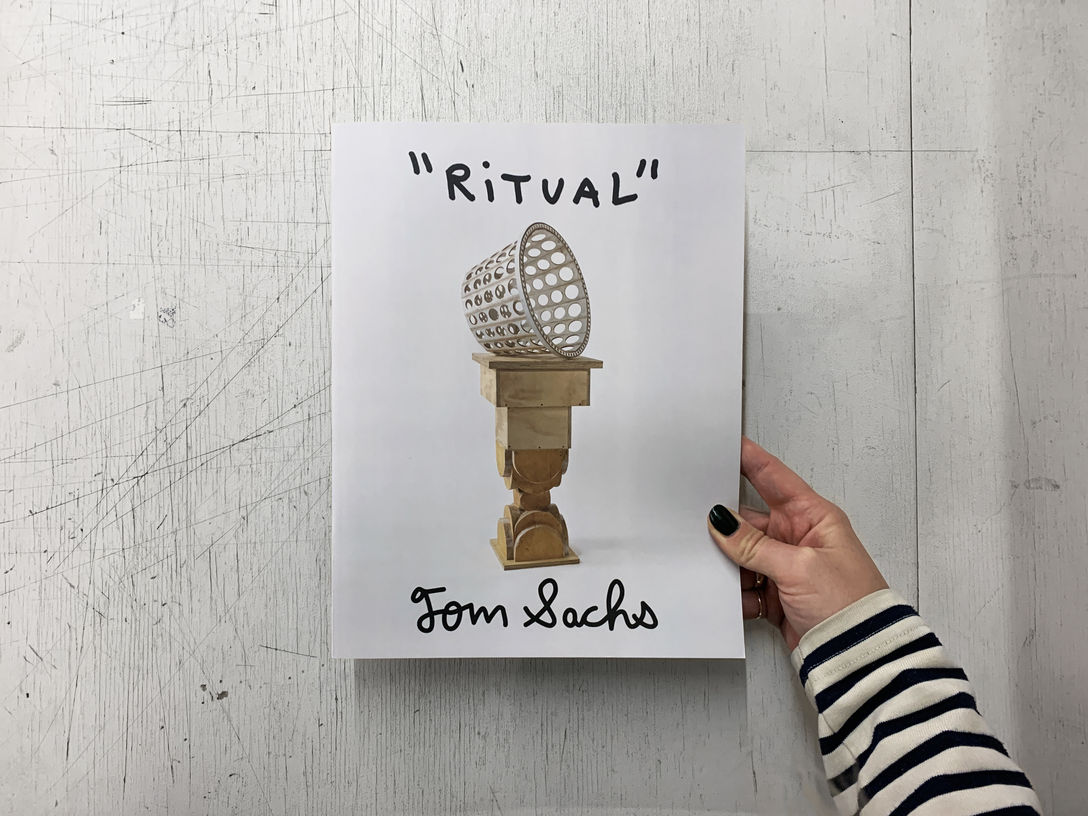

The ‘washer woman’ has been an archetype throughout art history, reflecting both strength and femininity, labour and sexuality. When addressed by Sachs in The Laundress (2015), the laundry basket becomes symbolic of the grey area between the public and private that can be observed in laundromats, where the mundane yet intimate rituals of daily life are performed in a shared space that has become intrinsic to the cultural landscape of the city. Sachs' laundry basket was created using an aerospace process, called lightening, developed by NASA to optimise the weight of an object while simultaneously increasing its strength.

The Laundress, 2015

Latex paint, polyurethane varnish, epoxy resin, plywood

144.1 x 70.8 x 70.8 cm (56.7 x 27.9 x 27.9 in)

The camera is a recurring element in Sachs' work. The earliest existing work by the artist is a clay replica of a Nikon SLR camera that he made when he was 8 years old as a gift for his father. The VX1000 was a DV tape camcorder released by Sony in 1995. It was intended as a 'prosumer' model, to bridge the gap between high-end consumer and low-end professional users. Playing off the consumer fetishisation of photographic equipment, Sachs' cameras deconstruct the technology of photography while at the same time revealing these ubiquitous machines as compelling subjects in their own right.

VX 1000, 2016Plywood, latex paint, cardboard, epoxy resin, steel hardware

165.1 x 45.7 x 45.7 cm (65 x 18 x 18 in)

The totem-like ICE (2020) is a quotidian object often found outside street-corner bodegas, where they greet customers like a gargoyle on a front gate. With three plywood cameras mounted on it, the sculpture becomes a panopticon. It introduces the issue of surveillance in urban spaces, like a contemporary ode to Michel Foucault's Discipline and Punish (1975) as illustrated by a stroll through a New York neighbourhood. The panopticon induces a sense of permanent visibility that ensures the functioning of power and is destined to spread throughout society, making power more economic and effective.

Ice, 2020

Plywood, authentic polymer and mixed media including steel hardware and security cameras

191.8 x 63.5 x 45.7 cm (75.5 x 25 x 18 in)

I think that I'm a very guilty consumer and one of the reasons why my work resonates with people is because I'm not just a critic living in the woods. I have a Kelly bag, drive a Mercedes van, I live in Soho, but I'm critical of it at the same time. — Tom Sachs

This sculpture replicates the leaf blowers used to clean lawns, gardens and street corners across America. The increasing ban of leaf blowers in wealthy neighborhoods like Palm Beach or Beverly Hills is perceived as a representation of class struggle because the conflict places professional gardeners, whose ranks are heavily Latino and Asian American, in opposition to the white people who hire them and yet complain about the noise their jobs entail. Aside from its contemporary political resonance, the slender, elegant and anthropomorphic shape of the sculpture is reminiscent of Constantin Brancusi's Bird in Space (1923).

Stihl Leaf Blower, 2020

Mixed media, including cardboard and epoxy resin

211 x 30.5 x 30.5 cm (83.1 x 12 x 12 in)

One of the most frequently shoplifted items in America, Tide is a laundry detergent that has also become a feature of the black market economy, as it is used as an ad hoc street currency for drug transactions. A 150-ounce Tide bottle can be traded for either $5 cash or $10 worth of weed or crack cocaine, earning the nickname of 'liquid gold' on certain corners. In recent years, store owners and managers have reported regular raids on their household-products aisle.

Tide Bottle (orange), 2020

Mixed media, including synthetic, polymer on cardboard and epoxy resin

168.3 x 39.4 x 33 cm (66.1 x 15.5 x 13 in)

An object used in recycling, the bottle rack is also charged with important art historical references. Porte-Bouteilles was famously Marcel Duchamp's first readymade in 1914, of which he made several successive versions. All of Duchamp's readymades were chosen for their inherent formal qualities, as he was extremely selective in picking a specific object. This version is an exact model in plywood of the bottle rack that belonged to Robert Rauschenberg, an artist of whom Sachs considers himself a disciple.

Porte-Bouteilles (Bottle Rack), 2016

Plywood, resin and synthetic polymer paint

168.3 x 39.4 x 33 cm (66.1 x 15.5 x 13 in)

The original version of Porte-Bouteilles (previously exhibited at Thaddaeus Ropac Paris Marais and now in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago) was selected by Duchamp for the 1959 exhibition Art and the Found Object in New York. Rauschenberg acquired it after the touring exhibition and asked Duchamp to sign it in 1960. He obliged, inscribing in French, 'Impossible for me to recall the original phrase M.D./Marcel Duchamp/1960', which is replicated in Sachs' version of the object.

Placed on bespoke pedestals referencing the pedestals of Constantin Brancusi (1876–1957), the works are elevated to the position of high art.