Overview

Fifty-five years to the day after its 1967 opening, Thaddaeus Ropac Paris Marais is delighted to present Sturtevant: Dialectic of Distance, an unprecedented exhibition retracing the performance of American artist Sturtevant (1924–2014) in which she recreated The Store (1961) by Claes Oldenburg.

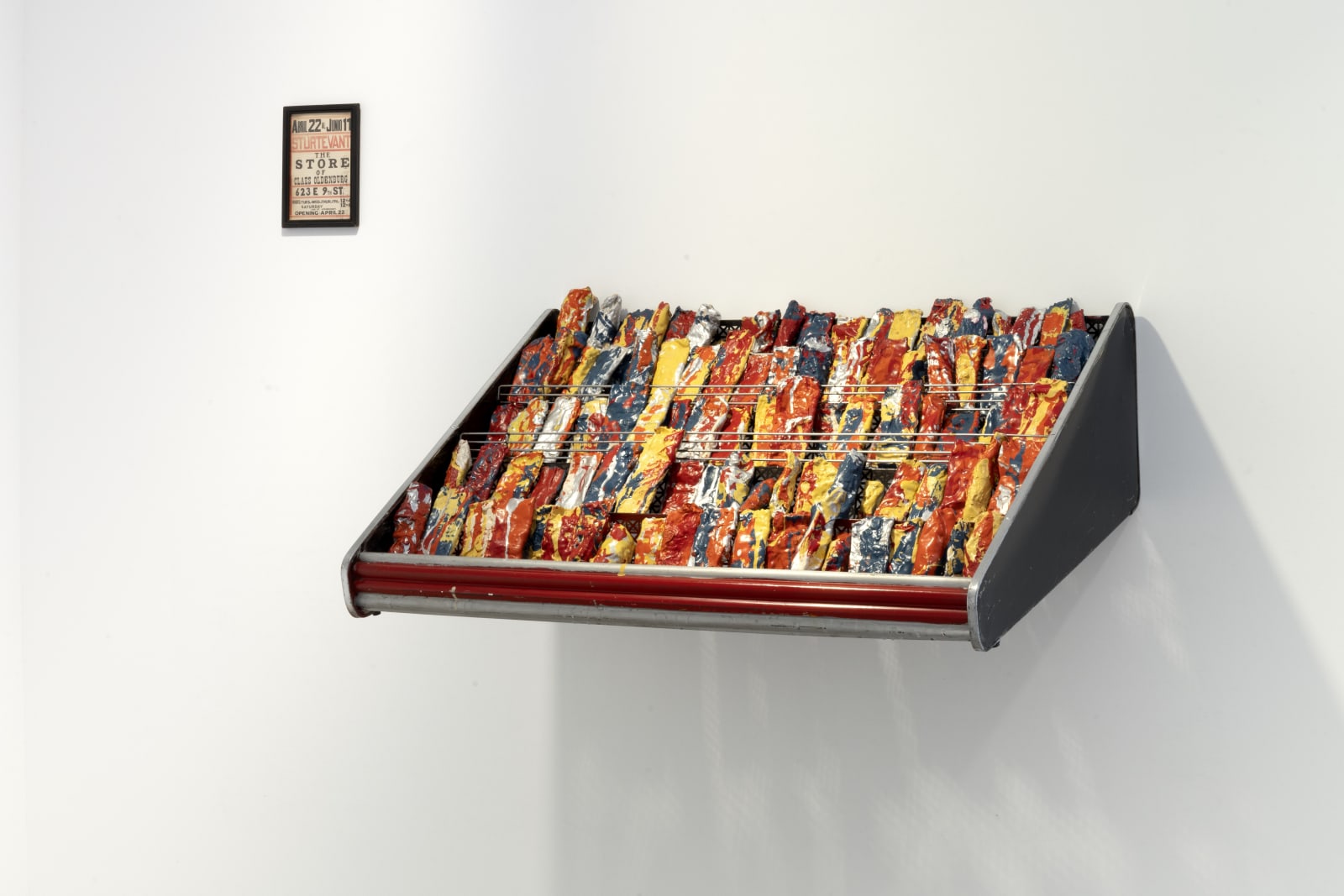

Known for her disconcerting replicas of works by her contemporaries that would become iconic, Sturtevant's practice challenges the prevailing discourse around originality and authenticity in art. The fourteen plaster objects on display were made by Sturtevant in the 1960s, based on those that Oldenburg had created for his Lower Manhattan shop. They are brought together for the very first time in the exhibition and will be shown alongside The Dark Threat of Absence, a 2002 video work in which Sturtevant re-enacts Paul McCarthy's film Painter (1995). Together, the two emblematic works will provide a rare insight into the pioneering artist’s multifaceted practice.

Fifty-five years to the day after its 1967 opening, Thaddaeus Ropac Paris Marais is delighted to present Sturtevant: Dialectic of Distance, an unprecedented exhibition retracing the performance of American artist Sturtevant (1924–2014) in which she recreated The Store (1961) by Claes Oldenburg.

Known for her disconcerting replicas of works by her contemporaries that would become iconic, Sturtevant's practice challenges the prevailing discourse around originality and authenticity in art. The fourteen plaster objects on display were made by Sturtevant in the 1960s, based on those that Oldenburg had created for his Lower Manhattan shop. They are brought together for the very first time in the exhibition and will be shown alongside The Dark Threat of Absence, a 2002 video work in which Sturtevant re-enacts Paul McCarthy's film Painter (1995). Together, the two emblematic works will provide a rare insight into the pioneering artist’s multifaceted practice.

A destabilising feeling accompanies Sturtevant’s exhibitions as her works continue to break the barriers and taboos of the art world. In 1967, Sturtevant rented a shop on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, in which she displayed a number of coloured plaster objects including dresses, cakes, hamburgers and cigarette butts as part of a happening re-enacting Oldenburg’s famous performance. The radical gesture was met with hostility: on the day before the show was due to open she was severely beaten by a group of schoolchildren, and ended up in hospital. Audacious and provocative, Sturtevant’s works generate confusion in order to elicit thought and spark, as she calls it, ‘fire’.

Among the small circle of avant-garde intelligentsia that Sturtevant was part of, some shared this feeling of incomprehension at the time of the happening. The Store by Claes Oldenburg, which had taken place only seven blocks away a few years earlier, was already a landmark of the Pop Art movement, as it circumvented the commercial structures of the art world and highlighted the increasing commodification of works of art. Sturtevant’s iconoclastic repetition of The Store took the Pop critique even further by exploring the implications and assumptions around creativity itself.

Each item in the shop, recreated from memory, was not an exact reproduction of one of Oldenburg’s objects, but rather, as Musée d’Art Moderne curator Anne Dressen described it, ‘a simulation of a facsimile.’ The dresses on display at Thaddaeus Ropac Paris Marais, for example, are uncannily similar to the ones found in Oldenburg’s Store. Sidestepping the notion of originality, the process of repetition is a way for Sturtevant to explore the tensions that inevitably arise through subjectivity. As she explained in a 2013 interview, ‘The appropriationists were really about the loss of originality and I was about the power of thought. A very big difference.’

Sturtevant’s approach resonates with the theories put forward by French philosopher Gilles Deleuze in his early masterwork Difference and Repetition (1968). In repeating the works of other artists through her own actions and movements, she creates difference, in the Deleuzian sense; that is, the distance that simultaneously separates and connects two entities. The exhibition’s subtitle, Dialectic of Distance, invites viewers to approach Sturtevant’s works on these terms, as it repeats, fifty-five years to the day after its opening, Sturtevant’s own re-creation of Oldenburg’s Store.

Also on view at Thaddaeus Ropac Paris Marais will be Sturtevant’s re-interpretation of Paul McCarthy’s 1995 performance Painter, titled The Dark Threat of Absence (2002). In Painter, McCarthy disguised himself as a cartoon-like character with exaggerated rubber prosthetics and wandered around a wooden set designed to look like an artist’s studio. He was dressed in a blue garment, halfway between a painter’s smock and a hospital gown, and periodically shouted ‘de Kooning!’ in a clear parody of the Abstract Expressionist painter. As a re-enactment of an artist acting as another artist, The Dark Threat of Absence represents a unique mise en abyme of Sturtevant’s practice.

At the same time, she pushes the critique of the image of the artist as a tortured genius even further in her version, highlighting the phallocentric nature of the myth with explicitly sexual close-ups and cutaways to hysterical crowds at pop music concerts. She describes a work in which ‘time is image, movement is thought, empty space is the exhaustive force – all forming a powerful totality that shoves and jolts the constructive parts.’ Ketchup bottles and phalluses alternate in quick succession, often reappearing as flashes on the screen as the video gradually moves away from McCarthy’s performance.

Made more than three decades after The Store of Claes Oldenburg, this later work clearly establishes a visual dialectic through the dual channel format of the video. At the start, both sides appear to be showing the same footage, but a time gap soon begins to appear, which turns into what the artist describes as an ‘agitated imbalance that is stuck and glued by transgression.’ This doubling up in Sturtevant’s re-creation emphasises ‘the infrathin discrepancy’, as art historian Anne Dressen terms it, ‘which makes all the difference for Deleuze: in essence, two peas in a pod cannot be identical, and every reprise puts restrictions on hyperrealism, because subjectivity inevitably creeps in.’