Vera Molnár

Overview

'I use simple shapes because they allow me step by step control over how I create the image arrangement. Thus, I can try to identify the exact moment when the evidence of art becomes visible. In order to guarantee the systematic nature of this research, I use a computer.'

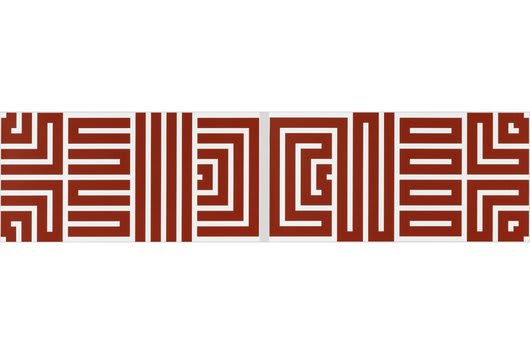

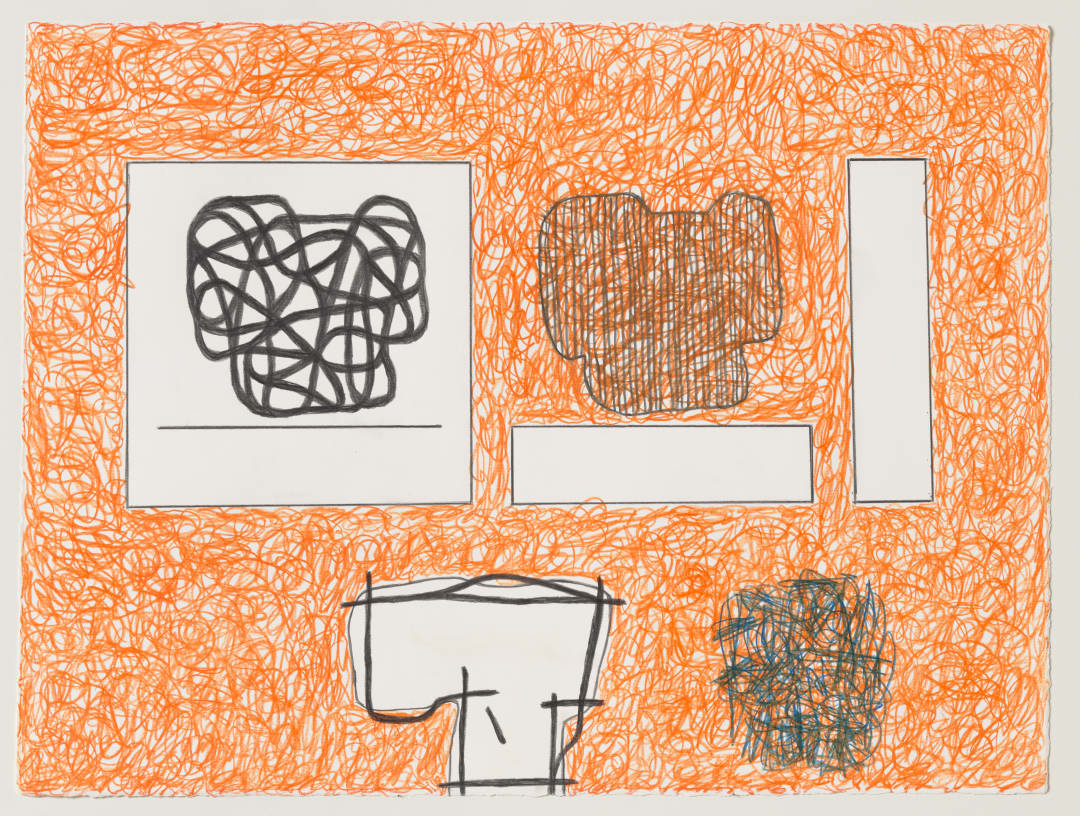

One of the early pioneers of computer art, Vera Molnár's radical systems-based approach helped establish the parameters for contemporary intersections between art and technology. Her geometric abstractions are created using a rigorous compositional method, governed by a predetermined set of mathematical rules that foreshadowed the development of computers. 'My life is in squares, triangles, lines,' the artist once said, referring to her focus on elementary forms. In the 1960s, she began implementing simple algorithmic programmes by hand, a method referred to as her 'machine imaginaire'. This assisted her in working systematically through all the possible permutations of a series, following a sequence of instructions and self-imposed limitations.

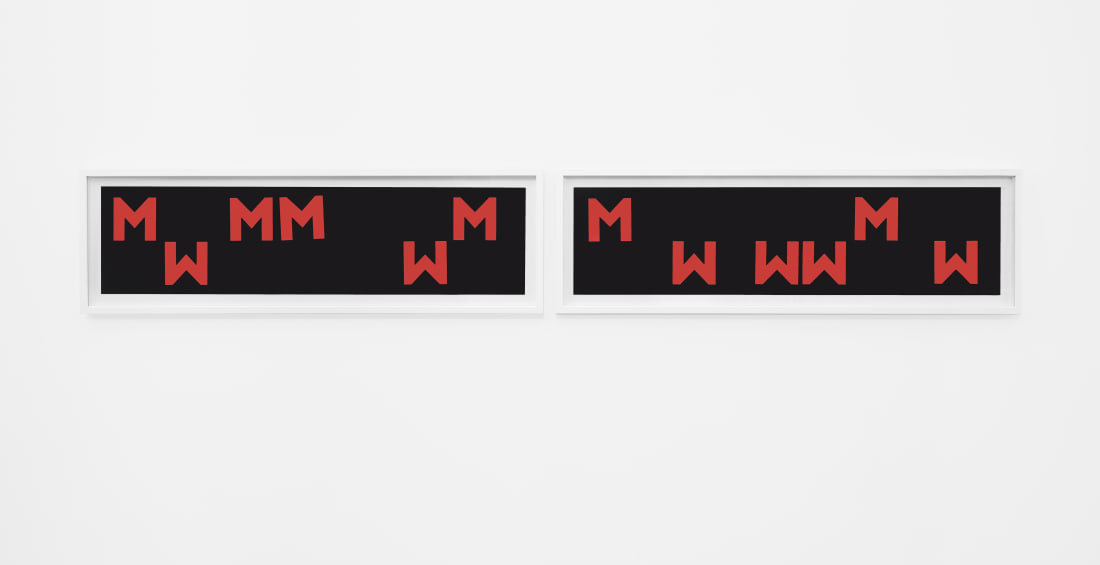

In 1968, Molnár first gained access to a computer in a Sorbonne research lab and taught herself the early programming language Fortran, which allowed her to input endless algorithmic variations into the machine. Using a language of 0s and 1s, she could feed instructions into the computer, which were then outputted to a plotter that produced line drawings with a moving pen. She experimented with repetitions and variations of the letter M – as in Malevich, Mondrian and Molnár – which operates as an abstract sign while also paying homage to her predecessors. Convinced that there is never a single solution to an aesthetic problem, she experiments with serial variations within and across works. She also explores the slippages between order and chaos, deliberately introducing a '1% disorder' to allow for a systematically determined factor of chance to influence her works.

One of the early pioneers of computer art, Vera Molnár's radical systems-based approach helped establish the parameters for contemporary intersections between art and technology. Her geometric abstractions are created using a rigorous compositional method, governed by a predetermined set of mathematical rules that foreshadowed the development of computers. 'My life is in squares, triangles, lines,' the artist once said, referring to her focus on elementary forms. In the 1960s, she began implementing simple algorithmic programmes by hand, a method referred to as her 'machine imaginaire'. This assisted her in working systematically through all the possible permutations of a series, following a sequence of instructions and self-imposed limitations.

In 1968, Molnár first gained access to a computer in a Sorbonne research lab and taught herself the early programming language Fortran, which allowed her to input endless algorithmic variations into the machine. Using a language of 0s and 1s, she could feed instructions into the computer, which were then outputted to a plotter that produced line drawings with a moving pen. She experimented with repetitions and variations of the letter M – as in Malevich, Mondrian and Molnár – which operates as an abstract sign while also paying homage to her predecessors. Convinced that there is never a single solution to an aesthetic problem, she experiments with serial variations within and across works. She also explores the slippages between order and chaos, deliberately introducing a '1% disorder' to allow for a systematically determined factor of chance to influence her works.

Born in Hungary in 1924, Molnár lives and works in Paris, where she moved in 1947 following her studies in painting, art history and aesthetics at the Budapest College of Fine Arts. She co-founded several important French experimental groups, including Groupe de Recherche d'Art Visuel (GRAV) in 1960 and Art et Informatique in 1967. Her first solo exhibition, Transformations, was shown in the gallery of the Polytechnic of Central London in 1976. Prior to that, she had participated in important group exhibitions such as Konkrete Kunst: 50 Jahre Entwicklung, organised by Max Bill at Helmhaus, Zürich (1960) and Cybernetic Serendipity at the Institute of Contemporary Art, London (1968). In 1976, she developed the Molnart software with her husband, the artist François Molnár (1922–1993). She was professor in fine arts, aesthetics and art history at the Sorbonne from 1985–90.

Molnár's work has received increased international recognition in recent years, with solo exhibitions at the Musée des Beaux-arts, Rouen (2007, 2012); Musée des Beaux-arts, Budapest (2010); Haus Konstruktiv, Zurich (2015); Musée des Beaux-Art de Caen, Caen (2018); Museum of Digital Art, Zurich (2019); and Museum Ritter, Waldenbuch (2020). This was followed by a major retrospective to mark the artist's 97th birthday at the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rennes, in 2021. She has also participated in group exhibitions including Chance and Control: Art in the Age of Computers, Victoria & Albert Museum, London (2018); Degree Zero: Drawing at Midcentury, The Museum of Modern Art, New York (2020); and Women in Abstraction, Centre Pompidou, Paris (2021). In 2022, she was selected for inclusion in The Milk of Dreams at the 59th Venice Biennale, curated by Cecilia Alemani. Molnár received the first D.velop Digital Art Award in 2005, was appointed Chevalier of Arts and Letters in 2007, and won the outstanding merit award AWARE in 2018.