A thrilling new take on Robert Mapplethorpe, by ex-Vogue editor Edward Enninful Edward Enninful reveals all about his first show to The Guardian

He shook up the world of fashion. For his next move, the sartorial supremo wants to change how we view the explosively provocative photographer. Edward Enninful reveals all about his first show.

‘It ended how I wanted it to end,” says Edward Enninful firmly, speaking a few days after his final issue as editor-in-chief of British Vogue hit the shelves. The parting cover is a paean to Enninful’s past, and his achievements at the magazine, featuring 40 iconic women he has worked with over the years, from Victoria Beckham to Oprah Winfrey, Dua Lipa and Anok Yai. But now his eyes are fixed on the future. His next venture is an unexpected move away from fashion and London – his take on Robert Mapplethorpe, in a show at Thaddaeus Ropac gallery in Paris.

[...]

Enninful, speaking by Zoom from his London home, seems the ideal match for Mapplethorpe, the photographer cum agent provocateur with a scrupulous eye, who challenged conventional ideas of beauty. “He questioned the idea of what portraiture is,” says Enninful. “What is beautiful? Who is allowed in? I believe I have done the same – we both questioned the status quo in our industries.”

Enninful’s career in fashion began soon after his family arrived in the UK from Ghana. At the age of 16, he became a model after being scouted by legendary British stylist Simon Foxton on the London tube. At the age of 18, Enninful became the youngest ever fashion director at an international publication when he was appointed to the role at i-D. After two decades there, he worked at Italian and American Vogue, as well as W. In 2016, he was awarded an OBE for services to diversity in the fashion industry.

It was Foxton who first introduced a teenage Enninful to The Black Book, Mapplethorpe’s explosive collection of 96 erotic photographs of black men. “I was a dark skin model with a bald head then,” he says. “I could see myself in Ken Moody.” A fitness instructor, Moody is often regarded as Mapplethorpe’s muse. “I loved the way Mapplethorpe used light. It was so powerful you wanted to touch the picture. There was a feeling that something new and incredible was happening in his work.”

Mapplethorpe’s treatment of the black male body has come under fire for what is seen as his exploitative and fetishistic gaze. Moody later wrote of a tense relationship with the photographer, who he claimed once called him an “Oreo”, because his manners were not “ghetto”. Enninful says: “Throughout history, black men have been portrayed in many ways. We’ve been used to create some of the most iconic images. We need to keep the conversation about objectification going. But we need to deal with images that define men and women – it can’t only be isolated to black men.”

Enninful’s own approach with the medium is more collaborative. “I was a model,” he says, “so I understand being on set and not having a say, when you’re at the service of the image and the shoot. I was very lucky to have people like Simon Foxton and [photographer] Nick Knight, who encouraged me to speak up. Modelling isn’t easy – you’re always told to shut up, your opinion matters less. So when I work with Kate or Naomi, we work together on stories, we develop characters – that’s something I really learned from those early days.”

Mapplethorpe became something of a talisman for Enninful as he hurtled full throttle into the London fashion scene in the 1980s, a pace he kept up in the following decade, long after Mapplethorpe’s died of Aids-related complications in 1989 at the age of 42. “Us kids who came up together in the 1990s – some of whom are now the world’s leading fashion photographers – we were all so influenced by Mapplethorpe. We were so inspired by the honesty in his pictures.”

Enninful’s take on Mapplethorpe is elegant, emotive and quietly disruptive, making evident their shared sensibility and profound concern with being seen. Combing through more than 2,000 images held in the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation archive, Enninful selected just 46. “I approached it as images of his work that resonated with me,” he says. “It was very instinctive.” After three decades working on printed matter, Enninful approached the exhibition like an editor, pairing the images up like a procession of double-page spreads.

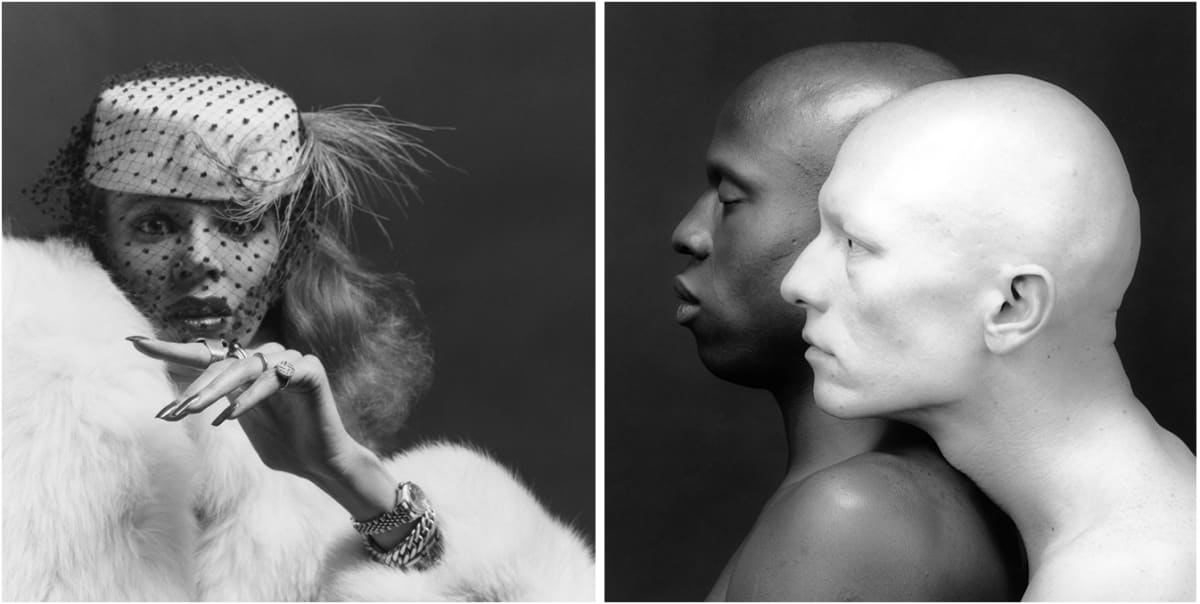

As you might expect, Enninful seems most attracted to the iconic images: old school glamour and high-society swank with a bit of brains thrown in. There’s author Fran Lebowitz, cigarette in hand, next to an ethereal Isabella Rossellini, while a 1988 portrait of Susan Sarandon holding her daughter Eva Amurri recalls Enninful’s March 2022 Vogue cover of Naomi Campbell with her infant daughter in arms. A full-body shot of a half-naked young Arnold Schwarzenegger, flexing his famous muscles, appears next to female bodybuilder Lisa Lyon, photographed from behind, wearing a fabulous dress, her body looking as striking and sculpted as Schwarzenegger’s. A well-known portrait, shot in profile, of Ken Moody and another frequent subject called Robert Sherman reminded Enninful of himself and his husband Alex Maxwell, a director of fashion videos.

The pairings echo Mapplethorpe’s fascination with duality and blurring binaries – flipping expectations of gender, high brow and low, beautiful and ugly, classical and subcultural. Where Mapplethorpe’s dogged perfectionism slides towards coldness and severity, Enninful’s juxtapositions draw out the humour and tenderness also present in his work. One pairing brings Embrace, an elegant 1982 portrait of two men, one black, one white, holding each other, alongside Charles Bowman, a sublime and sultry closeup from 1980 showcasing Bowman’s glossy, herculean torso. Both have something to say about power and masculinity, yet the contrast could not be more stark: softness and vulnerability versus lusty, muscular might. It’s a reminder of just how many sides Mapplethorpe had. “He was a master,” says Enninful. “But I think he was pigeonholed. I wanted to show the breadth of his work.”