Mandy El-Sayegh: Interiors

BY MARIA WALSH

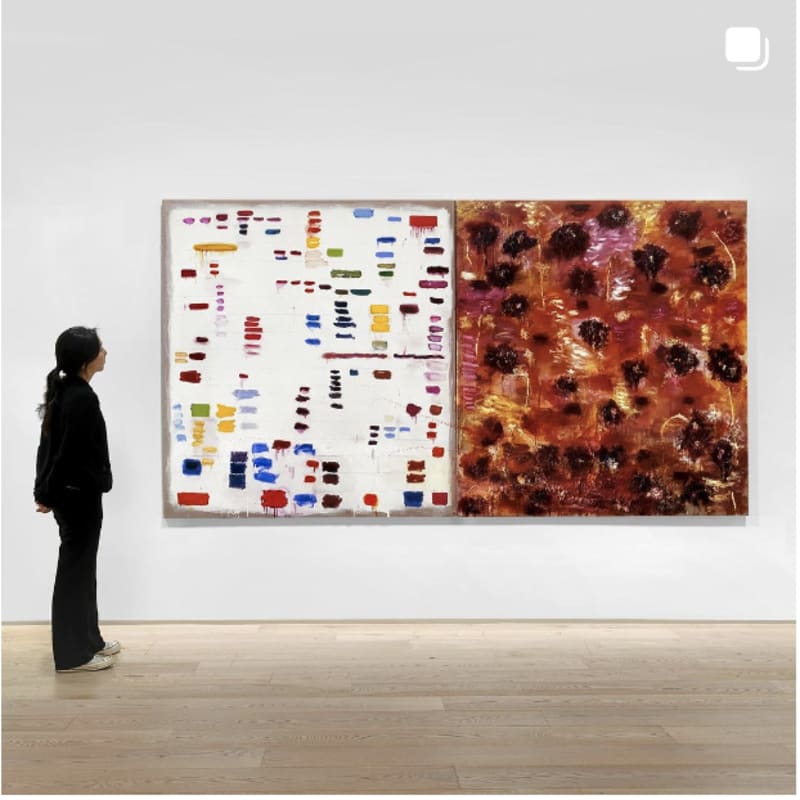

Mandy El-Sayegh’s paintings operate as objects and environments and, in a good hang, 2023, the first encountered work in ‘Interiors’, architectural adornment. Consisting of six collaged latex drapes hung at intervals in rows of two along the first-floor corridor, their sickly flesh-coloured hues of cream and rose add a slightly rococo element to the period features of the grand 18th-century former townhouse. Veiling the corridor’s clear line of vision, they act as elegant yet icky theatrical portals to the first installation: eight canvases from El-Sayegh’s ‘White Grounds’ series, 2017–, this iteration all from 2023, and Figuring Ground, 2023, a slightly sticky floorscape collage of newspapers and magazines, all whited-out by white oil gesso. As one walks over this ground, some head-lines, especially from the Financial Times, seep through the frenzied palimpsest.

All the paintings render various topologies – world maps, splayed wearables – in murky and lightly lacquered pastels, while two also form their own mini-installation, Tutmundo, 2023. White Grounds (Tutmundo Sudo) doubles as a projection screen for the video Akathisia, 2023, its sound produced by frequent collaborator Lily Oakes, and White Grounds (Tutmundo Nordo), 2023, doubled as a platform for a live performance, also called Akathisia, named a!er a movement disorder, that took place on 12 September. During this approximately 20-minute performance, El-Sayegh and dance collaborator Yuma Sylla, dressed in white sweatpants and hoodies, interacted with the video’s imagery, their bodies becoming expanded screens. Akathisia’s imagery ranged from still and moving footage of scar tissue, open wounds, fragments of other paintings, a grid that oscillated between garment and abstract pattern, as well as documentation of El-Sayegh’s studio processes: feet pummelling canvases, hands squeegeeing liquid across screens. This imagery became electrified when projected onto the backs of the performers’ white-costumed backs, particularly during Sylla’s solos in which she gyrated and vibrated to the soundtrack’s electro-beats, reminding me of Siri Hustvedts’s 2010 book Shaking Woman or the male performer in Doug Aiken’s Electric Earth, 1999, whose bodily movements mimicked the throbs of machinic objects on a nocturnal journey through the city. Fragments from El-Sayegh’s psychological meditations clatter in the mix: ‘over-identification confused my self ’s co-ordinates’. A standout sequence in what seemed like four distinct phases occurred when both performers, backs to the audience, bodies against the screen/painting, enact being searched at an airport, which could just as easily be prep for entry to a prison or other state institution. On the soundtrack, found sound of a woman with a US accent giving search instructions to a man added to the sense of bodily vulnerability.

When the lights went back on after the performance, the paintings’ subdued latency seemed even more extreme. While traces of the multiple layering processes that go into their making are evident, ie pasting, pouring, squeegeeing, peeling and dragging, the continuous erasure and re-inscription of painterly gestures and original printed matter results in a surface that hovers between opacity and translucency. Some fragments of words and images do stand out from the hand-painted wobbly grids that El-Sayegh uses to hold the barrage of material together, mainly actual banknotes and pages from Penthouse and other erotica. Enmeshed in the endless circulation of information in communicative capitalism, human exoskeletons are flayed open and flesh is fully transactional. This is especially the case in the four paintings in the series ‘Atlas works (All in your head)’, 2023, which also feature cut-out maps of Palestine collaged over the silk-screened world maps that centralise global majority countries. This iconographic emphasis is both general and personal: El-Sayegh’s father is Palestinian, her mother, Malaysian Chinese. Other standout word combos that feature in the series are ‘Autumn Clouds’ and ‘Sea Breeze’, which I initially read as invoking scents or sprays that cover bad smells. Reading up on the work, it turns out that they are code names for military operations on Gaza by the Israeli Defence Forces, their rendering in sweetly acidic colours inversely and opaquely inferring the horror.

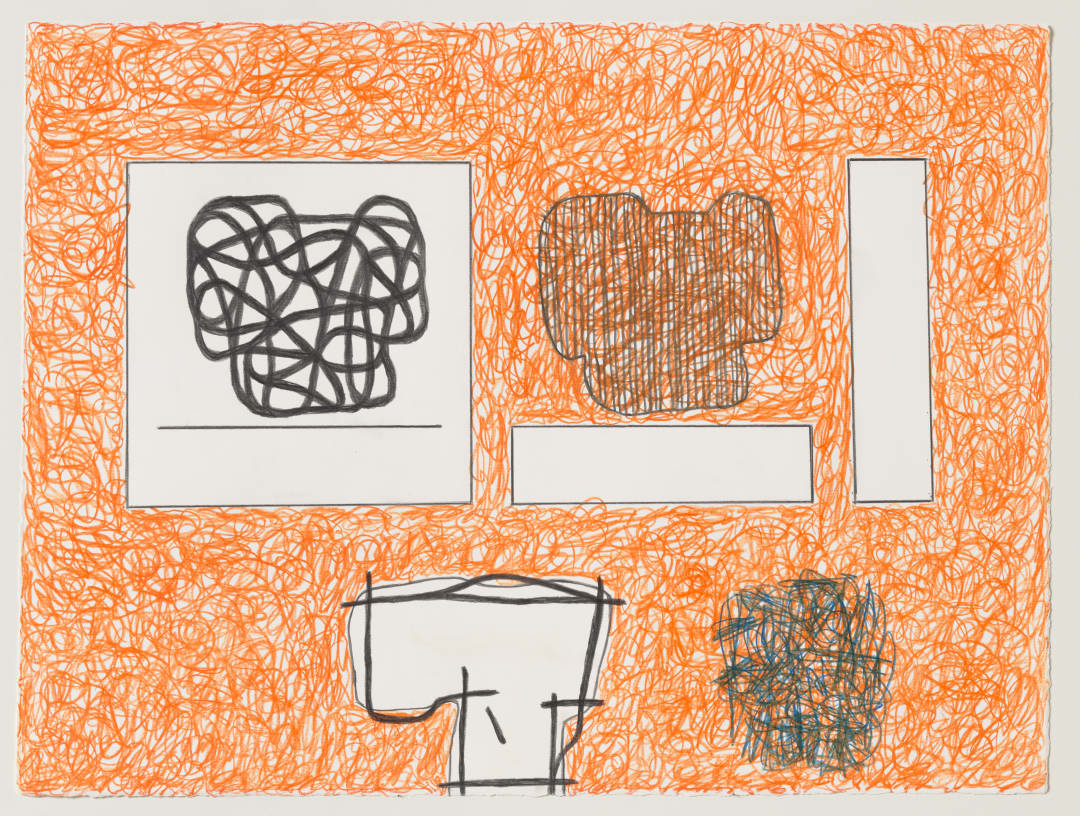

Gallery display units along the upper hallway feature items from El-Sayegh’s archive. Entitled consensual reality, they contain studio objects, books, old photographs and many items referencing mental and physical disease, including copies of the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). These references are a clue to the final installation of five paintings from 2023. Part of the series ‘Net-Grid’, 2010–, they were inspired by Sigmund Freud’s consulting room and his ethnographic collection of figurines and masks. Hung against walls covered with a collage of canvas fragments from El-Sayegh’s studio that evidence her pre-exhibitionary performativity, the floor is laid with Persian carpets alluding to the ones that Freud used to create a place of comfort and facilitate his patients’ free associations. As opposed to Freud’s ottoman couch, here visitors can lie on one of two vintage medical examination couches to gaze at the fragments of imagery and text in the paintings. The eyes and masks enmeshed in El-Sayegh’s grid in Net Grid (Blessing) could be said to infer the gaze of statuary that was a predominant motif and analytic method for Freud, but, as opposed to Freud’s Greek, Roman and Egyptian statues, El-Sayegh’s masks and eye imagery are fragments of a diasporic digital native that speaks back to the colonial imaginary of Freud’s time and place.

A 15-minute muffled sound piece on a loop, Scanded by Lily, 2023, also pervades the space. One of the aural fragments that emerges clearly from the mix is a voice – El-Sayegh’s? – repeatedly saying ‘there’s too much’. A male voice says ‘I can share my notes with you’. Ostensibly fragments from El-Sayegh’s own analysis, it sounded more like online chats and musings post-therapy. Occasionally a guttural choking or groaning sound emerged within the mix, but it was quickly layered over, much as the repeated image of a red-lipped orifice in the paintings did not break their surface flow. In fact, when I entered this room, two young Chinese fashionistas were staging their own impromptu performance using the painted environment as a backdrop for a shoot for a Chinese fashion brand.

In 1952, art critic Harold Rosenberg claimed that painting had become an arena in which to act rather than reproduce, an event rather than a picture – he was referring to Jackson Pollock. El-Sayegh also works on the floor. Di$erences of gender and racial heritage aside, in the digital era, painting could be said to be an arena in which to reassemble. In El-Sayegh’s multi-layered reassemblages, the detritus of personal and global informatics are meshed in surfaces that partially cleanse their messiness, though the traces of commodified desire seem inescapable.

Maria Walsh is author of Therapeutic Aesthetics: Performative Encounters in Moving Image Artworks, 2020/22.