Any Warhol, Mick Jagger: Jet set life as seen by Bob Colacello at the Ropac gallery By art critic and curator Eric Troncy

By Eric Troncy

Close to Andy Warhol, Bob Colacello frequented both the avant-garde and the jet set, immortalizing their parties and everyday lives between 1976 and 1982. Until March 4th, his legendary photos of a free and flamboyant era are on view at the Thaddaeus Ropac gallery in Paris.

Born in Brooklyn in 1947, and raised on Long Island, he currently works for the Peter Marino Art Foundation in the Hamptons. His living-legend status doesn’t entirely depend on the 2004 book he published on Ronald and Nancy Reagan (“Half the art world stopped talking to me,” he recalls, though that hasn’t put him off planning to write the second volume soon) but rather on the time he spent with Andy Warhol in the 1970s – time he frenetically documented with his camera, a little Minox he always carried with him. Eighty of his photos, shot between 1976 and 1982, are currently on show at Thaddaeus Ropac in Paris (Marais), while a book of them has just come out titled It Just Happened.

Bob Colacello, photographer of jet set's golden age

In his introduction, Bob Colacello recalls the accidents of life that turned his existence into a delicious back-and-forth between the avant- garde and the jet-set. “It just happened that at the parties we were constantly going to in New York, Los Angeles, Paris, and London, lesser-known people kept blocking my view of better-known people, but I took the pictures anyway, because I realized parties were like that, producing a layered look that I came to see as my style. It just happened that the 1970s was the most wide-open decade since the Roaring Twenties, and everyone wanted to be in the mix – young and old, gays and straights, blacks and whites, millionaires and hustlers – culminating in the ultimate decadent disco, Studio 54.”

The literary conceit of repeating “It just happened” makes me think of the “And just like that” in each episode of the Sex and the City reprise, which, 20 years later, shows Carrie Bradshaw struggling with an era whose aspirations she finds dismal and bizarre (for example, the scene where she’s astonished that her lover asks permission to kiss her) and that make her miss her youth. Colacello seems similarly regretful with respect to his own youth “when they just stole your wallet without hacking your bank account,” as he recently told Le Monde.

Photographs showcasing an era of freedom

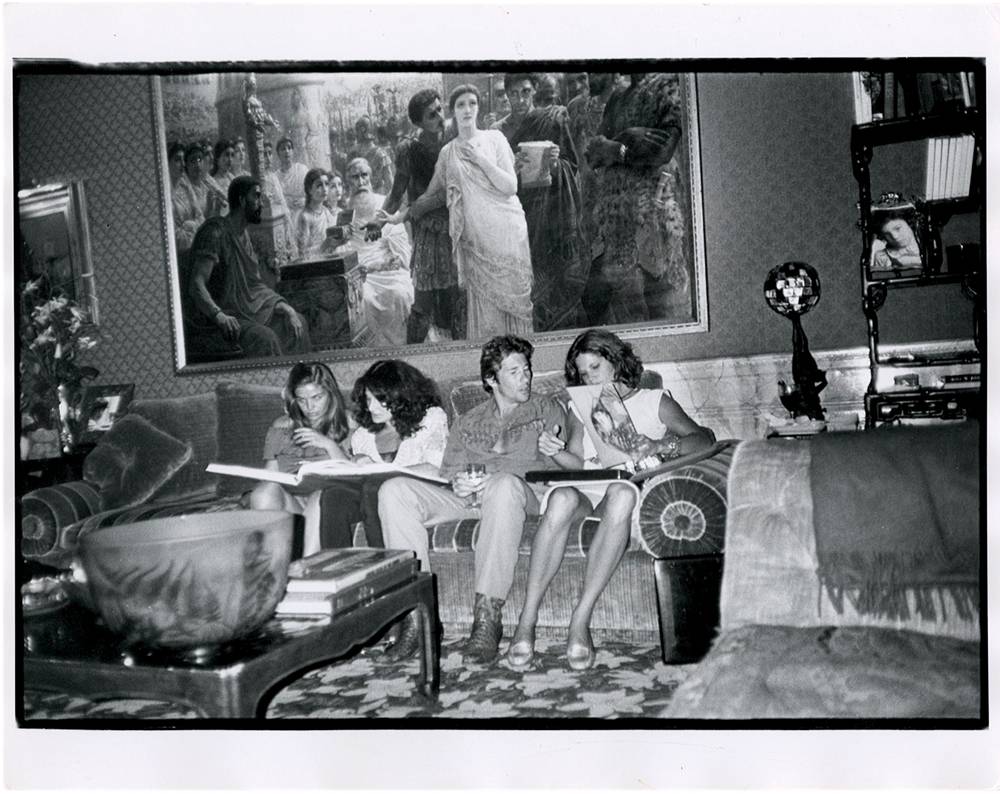

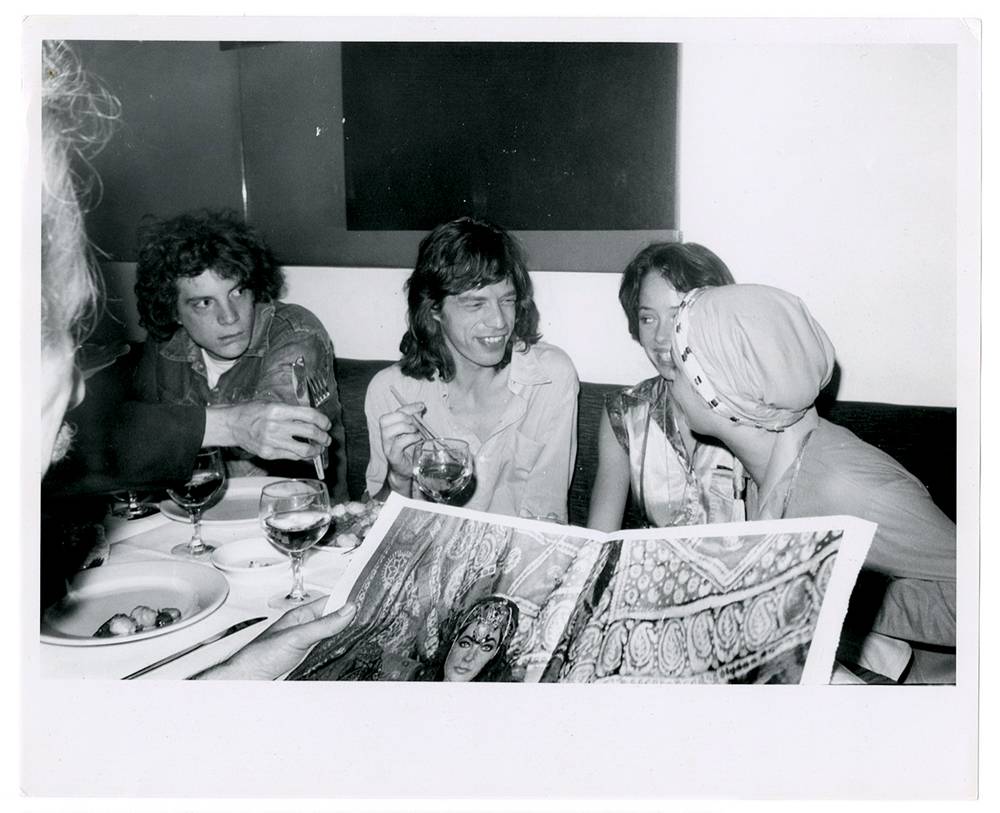

His photos also now appear in a nostalgic light, portraying as they do an era whose liberty and flamboyance seem to have made the generations that followed want to free themselves from them by imposing all sorts of rules in the name of the politically correct. In Colacello’s candid shots, we find a whole host of larger-than-life figures recorded in a black and white that exaggerates their character as historical documents: Warhol, of course, often at home, for example eating from a plate on his lap, a photo to which Colacello added the hand-written caption: “Andy eating, tape recorder on his lap. He called it ‘My wife, Sony.’” But we also see, among other luminaries of the time, Christina Onassis, Paloma Picasso, Jacqueline Bisset, Rudolf Nureyev, Estée Lauder, Norman Mailer, and Truman Capote. The author of Breakfast at Tiffany’s was shot, among others, with Warhol during a bookstore signing: “After he was banned from international society, Truman started writing for Interview, and would sign copies of the magazine with Andy, here at a bookstore in Southampton,” reads Colacello’s caption.

Like most of his photos, this one is a bit blurry and perfunctorily composed: the subjects are not posing but captured in the instant, as though life was hurtling by at top speed and the shutter caught a random nanosecond. But because it was him be- hind the viewfinder, and because he had access to everybody, the subjects photographed have an air of intimacy, including the German artist Joseph Beuys, shot at the Lucio Amelio Gallery in Naples, in 1980, with Warhol. The caption reads, “It wasn’t clear if Beuys appreciated Andy encouraging his teenage daughter to become a model, when they met again in Düsseldorf the following year.”

The “default” style of his photos seems to have found an echo decades later in fashion photography and, in truth, their fascination is not entirely divorced from their uncertain status, which is just as lopsided as their on-the-hoof composition. While they’re certainly not artworks, they could be considered to a certain ex- tent historical documents, as well as diary entries, reportage, and also vestiges and relics. This indeterminate status also portrays a bygone age that has been replaced by one where it seems that everything must be defined, outlined, and circumscribed within its ambitions – ambitions that are easy to understand and, consequently, to consume.

The most effective portrait of Colacello is, to my mind, that written by Pat Hackett in the introduction to Warhol’s famous diary, which, as his “friend and long-time collaborator,” she edited, in light of her daily phone conversations with him. “Bob Colacello, who had graduated from Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service and had come to the Factory by way of writing a review of Trash for the Village Voice, was working by this time mainly for the magazine (now, with a slight title change, called Andy Warhol’s Interview), doing articles and writing his column, OUT, which chronicled his own around-the-clock social life and dropped a heavy load of names every month. In 1974 Bob Colacello (by then he’d dropped the “i”) officially became the magazine’s executive editor, shaping its image into a politically conservative and sexually androgynous one. (It wasn’t a magazine with a family readership – one survey in the late 70s concluded that the ‘average Interview reader had something like .001 children.’) Its editorial and advertising policies were elitist to the point of being dedicated – as Bob himself once explained, laughing – to ‘the restoration of the world’s most glamorous – and most forgotten – dictatorships and monarchies.’ It was a goal, people pointed out, that seemed incongruous with Bob’s Brooklyn accent, but this didn’t stop him from going on to specify exactly which monarchies he missed most and why.”

His friendship with Andy Warhol at the core of an exhibition

The Colacello photos shown in the exhibition essentially document his time with Warhol, until that fateful day of 6 January 1983, which Warhol recorded in his diary: “When I got to the office, Vincent gave me a letter. It was from Bob. He had resigned ... I was happy for Bob. ... With respect to Bob’s departure, it wasn’t be- cause of the money, he earned a lot ... If he’s found a good job, I’m happy for him. Only he shouldn’t have re- signed without notice. That’s not nice. And it’s not professional.” Forty years later, Colacello corrected, “We all worked for Andy for nothing.” So the breakup was perhaps a question of money after all, even though Colacello also explained, in 2014, ironically in Interview: “I was 35, and it was time to move on. I was tired of Andy – then in his anorexic Zoli model phase – fed up with the antics and intrigues of his playmates ... So, yes, it was a bad breakup, but I slowly reconciled, because there was a deep reservoir of shared experience and affection from working together so closely for so long and so productively.” That same year, Colacello began collaborating with the magazine Vanity Fair.

His photos have an undeniable documentary value, since a whole era is captured in them, and the way it differs from the times we’re living in today becomes cruelly clear as we peruse them. They are also a fascinating biography of a man who, with his “It just happened,” claims that chance played a primordial role in his destiny. “So here we are. I never planned or plotted any of this,” he writes. “I have, however, always fol- lowed my mother’s dictum: ‘When opportunity knocks, open the door!’ I’ve walked through a lot of doors.”

Bob Colacello’s exhibition “It Just Happened, Photographs 1976–82” is currently on view at the Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery, Paris Marais, until 4 March 2023.