In Other Words: Revolutionary Rauschenberg

How the artist remains so relevant today

Art history can be a brutal editor. In the interests of big-picture clarity and precious wall space, the oeuvres of most artists of the 20th century have been snipped like poodles to within a millimeter of regulation standards. Take Robert Rauschenberg, for example. General wisdom has it that the artist’s real importance lies in that critical ten-year period when he first explored the proverbial gap between art and life: beginning with the “Combines” that he made between 1954 and 1964, along with the silkscreen paintings of the early 1960s. The art market makes for an even more merciless editor, filtering Rauschenberg’s value through an even narrower funnel.

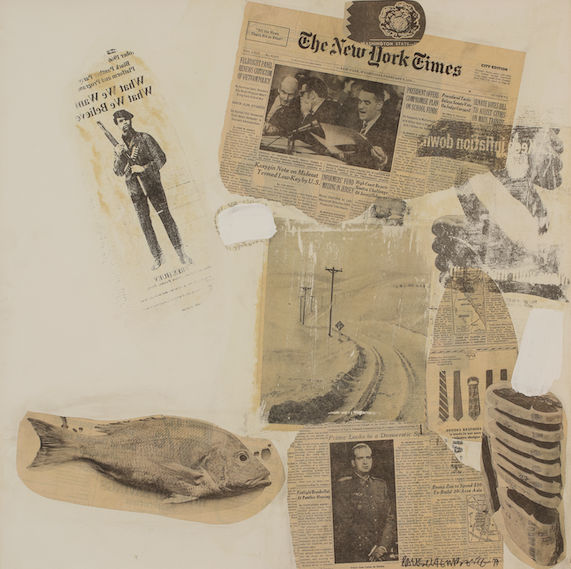

We have been led to believe that, barring a pocket of invention here and there, Rauschenberg’s ingenuity slowed after the early 1960s. How wrong we were. A recent visit to the Rauschenberg Foundation introduced me to, amongst other great and illuminating works, a series of collages made in 1970 as preparatory works for Currents (1970), a 54-foot-long silkscreen that, at the time, was the largest print ever made.

Preparatory, my foot. Those collages are remarkably potent and compositionally rigorous, simultaneously echoing the great invention of Cubism and presaging the media influence of the Pictures Generation that would emerge later in the decade. There is the occasional and astonishing flick-of-the-wrist gesture of paint. Rauschenberg’s work is an encyclopedia of imagery—each precisely chosen—that also functions as a time capsule of the heated social, political, sexual and environmental protests and liberations of the time. Unfailingly, Rauschenberg hits the nail on the head, creating works that express the urgency and impassioned principles that drove that tumultuous time, when even the supposedly pure artistic gesture of conceptual art could not be viewed independently of a political position.

Urgent activism triggered by catastrophic threats to the environment as well as real social, economic and judicial inequality arising from issues of race, gender and sexuality—all represented so vitally in these collages—are as urgent today, as if time hasn’t meaningfully moved on these past 50 years. In these turbulent times, Rauschenberg’s little-known dynamic, exciting collages are especially contemporary and vital. Currents is more current than ever: a time capsule where time appears to have stood still, equally capable of being a rallying cry for the activism of today.

You can feel it pouring out of the pores of these works—that we are on the precipice of a major reconsideration of the renewed relevance of later Rauschenberg for a younger generation of artists, curators and collectors. I hope that, before too long, there will be a major retrospective of these later years.

The earlier years are also ripe for rediscovery. For those of us old enough to remember, there was a revelatory exhibition of Rauschenberg’s work in 1992, during that brief period when the Guggenheim Museum had a great exhibition facility in SoHo (now home to Prada), entitled “Robert Rauschenberg: The Early 1950s”, curated by Walter Hopps, founding director of the Menil Collection. The show was a treasure trove. It demonstrated Rauschenberg’s staggering range of artistic invention in the half-decade preceding what we had previously understood to be the beginning of the important years.

In those few years, he created works of a scale and breadth few artists achieve in entire lifetimes: the most radical monochrome paintings ever made (and more than a dozen years before the term Minimalism was coined); alchemical experiments in object-making in vivid palettes of gold and red; tabletop sculptures with the material energy of abstract expressionism, as poetically precise as a haiku; life-size prints spray-painting the outline of the human body in radiant blue (years before Yves Klein made his first Anthropometries); and, one of the most radical artworks in the history of art—the Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953).

Ultimately, the importance of the present will largely be defined by the future of art, as has usually been the case. The art of today is constantly repositioning our frames of reference for the art of the past: the notion that artistic importance is shifting and relative is something I have always taken as a given. No artist represents this more for me than Rauschenberg. For years, though, Rauschenberg was almost a symbol. But now I am reminded that Rauschenberg’s work—which was always so of its time—is also, because of its generosity of spirit—timeless, with so much more to reveal and to teach us.

Robert Rauschenberg, Study for Currents #28 (1970) © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Robert Rauschenberg, Study for Currents #17 (1970) © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation