Marcel Duchamp’s 18 Most Puzzling Artworks, From Hypnotic Bicycle Wheels to Visions of Robotic Sex

Everything related to the great artist Marcel Duchamp is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma, as Winston Churchill once said of Russia around the start of World War II. While no artist is open to as many different readings as a nation of millions, Duchamp came as close as any over the course of a career that began in the first decade of the 20th century and continued on through his death in 1968.

Interest in Duchamp has only intensified as his influence has become more inescapable, with recent evidence including the tribute-paying documentary Marcel Duchamp: The Art of the Possible and an extensive exhibition of his work as collected by Barbara and Aaron Levine at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C. Few figures have ever done as much to slyly and shrewdly ask what art means—and, in a typically Duchampian manner, to suggest that any worthwhile answer will only lead to more and more questions over time. To survey some of that ongoing inquisition and response, here are 18 of the artist’s most puzzling works.

Coffee Mill (1911)

As with everything by Duchamp, the seemingly simple Coffee Mill opens up a wormhole of interpretations and associations. It counts as his first of many paintings of machines—subject matter that interested Duchamp in terms of objects and apparatuses but also as symbols for the systems and processes that undergird so much of modern life. Some have also pointed out the likeness of its design to a mandala, signaling his interest in mysticism and modes of spiritual thought. And more immediately apparent: the tiny arrow up top, which works to put the painting in motion.

Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912)

Motion is shown in full force in Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, a vision inspired in part by chronophotography—a means for making images with high-speed exposures to show something moving in a sequence. To try to make sense of the painterly decisions that figured in any one isolated area of the canvas is to miss the proverbial forest for the trees—and what a forest it is. For all his punning and provocation and cerebral posturing, Duchamp could also be a master painter when he wanted to be. Though not everyone shared the sentiment at the time: Nude was famously derided when shown at the 1913 Armory Show in New York and, as cited by Calvin Tompkins in his Time-Life “Library of Art” book The World of Marcel Duchamp, a newspaper in Chicago advised viewers to “eat three Welsh rarebits and sniff cocaine” if they wanted to understand the painting.

Bicycle Wheel (1913)

The alternately confounding and entrancing Bicycle Wheel is one of Duchamp’s first “readymades”—a series for which he transfigured plain old objects into works of art through simply conferring such status upon them by his own decree. It ranks as one of the most radical artistic gestures of any kind ever, and the ramifications of it are still shaking out more than a century later. In certain ways it points back to the early Coffee Mill and forward to a chocolate grinder that would take on great significance for Duchamp in the future. And in any case, as curator Michael R. Taylor says in the documentary Marcel Duchamp: The Art of the Possible: “Every other work of art that you’ve looked at is a problem, a game, that goes on between your eye and the surface of that work. [But] now you’re looking at a bicycle wheel and that line of sight goes from the bicycle wheel not to your eyes but four inches back further into your brain—because now you have to ask yourself all kinds of questions about why is that bicycle wheel there.”

3 Standard Stoppages (1913–14)

Described in the same documentary as “a para-scientific operation,” 3 Standard Stoppages involved Duchamp’s dropping three pieces of one-meter-long thread and letting their haphazard undulations stand in as different—and far less rational—units of measure. Incorporating the element of chance called into question the importance of the artist’s hand (even more than the readymades did). And the Stoppages presaged so much so-called “process art” to follow, in that its most meaningful register remains as an experiment that calls less attention to the resulting artwork than to the experiment itself.

Comb (1916)

Comb is another readymade whose plainness could not be more plain. Once again, Tompkins (one of the true greats among many devoted Duchamp chroniclers) in his Time-Life book: “When three readymades were included in an exhibition at the Bourgeois Gallery in New York in 1916, Duchamp insisted that they be hung unceremoniously from a coat rack at the gallery door, where, to his unfeigned delight, nobody even noticed them.” Of all the readymades, Comb held a special place in Duchamp’s heart because its undesirability made it so that it was never stolen. And apropos of nothing that is even remotely clear, it was inscribed with absurdist words in French that translate as “three or four drops of height have nothing to do with savagery.”

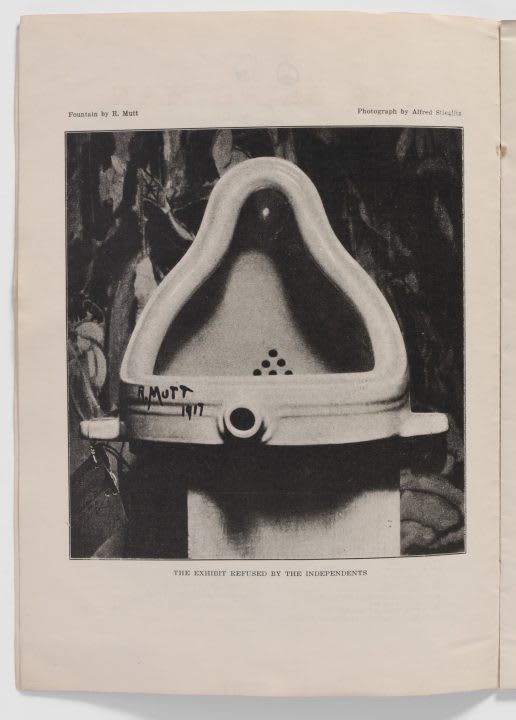

Fountain (1917)

Duchamp’s most notorious work—a mass-produced urinal sent in to be considered for a Society of Independent Artists exhibition under the alias R. Mutt—was not just a piss-take. It was actually oddly alluring; the storied photographer Alfred Stieglitz worked closely with Duchamp to take its portrait, and later wrote about the result: “The Urinal photograph is really quite a wonder – Everyone who has seen it thinks it beautiful – And it’s true – it is. It has an oriental look about it – a cross between a Buddha and a veiled woman.” Many have seen sexual aspects in it too. In Marcel Duchamp and the Art of Life, a recent book about the artist’s interest in esoteric rituals and erotic activities, Jacquelynn Baas writes, “As photographed by Stieglitz the urinal can also be perceived as a vulva, with the point of light at the top as the clitoris and the hole at the bottom as vagina.” And further on the matter, in reference to tantric practice that involves sprinkling water on fire to change it into a gaseous state: “In tantric ritual practice, emission of semen into the yoni is understood as an offering that parallels this ‘fall’ of water into the fire, generating what Duchamp called the illuminating or enlightening gas (‘gas,’ from the Greek khaos: ‘empty space’).”

Hat Rack (1917)

Another readymade, Hat Rack was for a time suspended from the ceiling of Duchamp’s studio to cast a strange, octopus-like shadow that could also be said to suggest the existence of an extra dimension beyond what we can see. Giving visual presence to the fourth dimension was a significant undertaking for Duchamp, whose art worked and played with the notion in numerous ways. If 2-D painting could represent 3-D space, then perhaps 3-D space is itself a rendering of an elusive but ever-present 4-D realm that could be evoked, if not exactly represented. It’s kind of like a shadow: an observable entity that is in certain ways not really an entity at all.

T um’ (1918)

T um’ is like an autobiography and a self-immolation in paint. It was commissioned to be hung over a bookcase (which accounts in part for its unusual shape), and for what would be his last painting on canvas, Duchamp focused on references to past works in a typically pointed and playful manner. The shadow of Hat Rack looms on the right-hand side, with Bicycle Wheel and 3 Standard Stoppages on the left. The best part is the odd black shape just to the right of the center: an actual bottle brush that juts out from the canvas and casts a real shadow of itself amid the otherwise painted shadows. (Little safety pins near it are also real safety pins, throwing the illusionistic aspect of the painting into an even more surreal spin.) But the even better best part is the title, which seems to be an abbreviated allusion to a French phrase directed at painting itself. Its translation: “You bore me.”

50 cc of Paris Air (1919)

Air is apparent in a glass vial that Duchamp purchased at a drugstore and filled with a little bit of French ambience ready to be transported all over the world. Or is it? As noted on the website of the Philadelphia Museum of Art—the holder of the most important collection of Duchamp’s works and a must-visit for anyone who falls under the artist’s sway—the work’s “precise meaning was rendered even more unstable in 1949, when the ampoule was accidentally broken and repaired, thus begging the question: Is the air even from Paris anymore?”

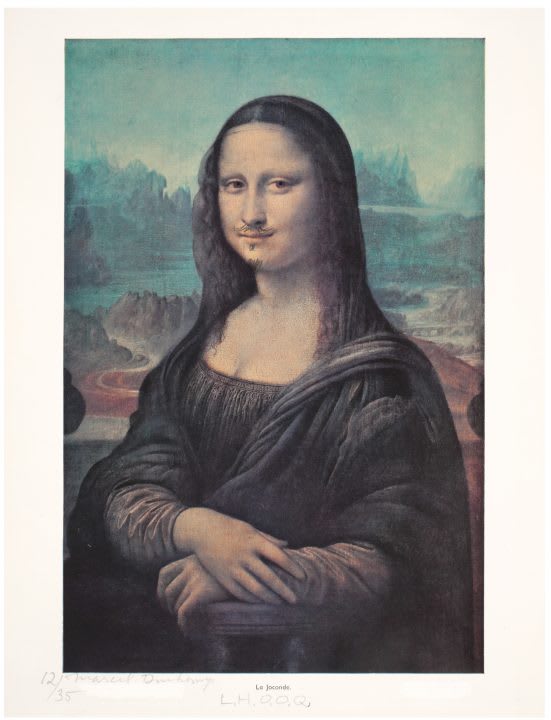

L.H.O.O.Q. (1919)

A postcard image of the storied Mona Lisa supplied with a mustache and goatee as if from the hand of a mischievous teenager—these are the makings of yet another great and in so many ways ridiculous work of art by Duchamp. Mixing signals of gender was a regular habit for him, as evidenced by his female persona identified by the alias Rrose Sélavy (a pun on “eros, that’s life”). And the capper on this work is the title, which, when enunciated, suggests the sound of the French declaration “elle a chaud au cul”—or “she has a hot ass.” (Another fun fact: Duchamp later signed an unadulterated print of the Mona Lisa with the addition of subtitle Rasée—or, “shaved.”)

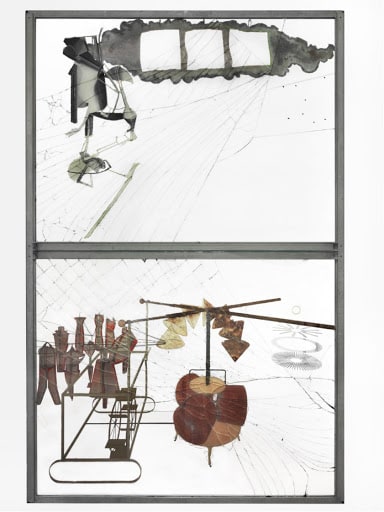

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) (1915–23)

One could spend a lifetime wondering about this abstruse and allusive painting on glass—a surface, it’s worth noting, that in its transparency would seem to count as not exactly a surface at all. As might be less than immediately clear, the work’s renderings of the figures and the actions they perform are all about sex. The robotic-bird-like “Bride” (a figure Duchamp had painted in other forms before) stands at the top left, generating mists of “illuminating gas” that raise the libido of the bachelors (nine of whom are in the form of casting molds at the bottom left). It gets lots more complicated than that, but the gist is that the whole mechanical world depicted would then start churning in a way that mimics carnal action (in part by the operation of a chocolate grinder in the lower middle that refers back in ways to earlier works like Bicycle Wheel and Coffee Mill). Also worth noting is the fact that the fragile work smashed to smithereens while being shipped, and Duchamp (not necessarily displeased by such a fate) painstakingly put it back together again.

Door: 11 Rue Larrey (1927)

A pun that doubles as a sort of portal, Duchamp’s spirited design for Door: 11 Rue Larrey made it such that he could close one room in his live/work space in Paris while opening another—but they could not be shut simultaneously. The two rooms were a studio and a bathroom, and the artist liked the architectural intervention so much that years after moving elsewhere, he returned to the apartment (then being rented by a fellow artist) and traded a replacement for the original, which he took for his own.

Rotoreliefs (1935)

For an artist who derided the mere eye candy of what he called “retinal art” (art that prioritizes the eye over more important matters of the mind), Duchamp made some extremely pleasing things to look at over the whole of his career. High on the list are his Rotoreliefs, a series of double-sided disks meant to be spun on a record player at 40–60 rpm in a manner that turns mesmerism into a literal pursuit. The designs make it seem as if depth opens up in front of you, and such disks figured in an early experimental film that Duchamp called Anemic Cinema.

Bookbinding for Ubu Roi (1935)

Designed in a collaboration between Duchamp and Mary Reynolds, the binding for this copy of Alfred Jarry’s wild pataphysical play Ubu Roi spells out the name of the main character as it opens. “Both Duchamp and Reynolds were so pleased with the final work,” according to the website of the Art Institute of Chicago, “that another copy was bound identically for the American collectors Walter and Louise Arensberg” (who amassed the fabled collection of Duchamp works held by the Philadelphia Museum of Art).

The Box in a Valise (1935–41)

Like the Austin Powers joke about a factory that makes miniature models of factories, The Box in a Valise comprises little renderings of dozens of works spanning more than two decades of Duchamp’s career up until the point he thought to make his oeuvre fit into a carrying case. There’s a mini Fountain and a less than Large Glass; there’s a small ampoule of Paris Air (fewer than 50 cc) and a tiny T um’ (a model of a work that is itself a model). All of it amounts to a sort of museum in portable form, and it figured in the engagement with different modes of presentation and exhibition-making that would occupy Duchamp for the rest of his life.

16 Miles of String (1942)

For the first international Surrealism exhibition in New York, Duchamp devised an unusual atmosphere in a stately mansion accentuated by what he famously called “16 miles of string.” The material swooped and stretched and drooped and floated, and as many noticed (including some artists in the exhibition who were none too pleased), it made it difficult to see the art on display. As Elena Filipovic surveys the story in her recent book, The Apparently Marginal Activities of Marcel Duchamp, a review in the New York Times showed a liking for the string: “No use trying in a matter-of-fact way to describe what he has accomplished,” wrote the critic Edward Alden Jewell. “The net result, geometrical at least by implication, in its interlacing and festooning, is appropriately weird and devious. It forever gets between you and the assembled art, and in doing so creates the most paradoxically clarifying barrier imaginable.” For the opening of the show, Duchamp also hired children to dress up in sporting uniforms (including cleats) and play disruptively amid the tuxedo-clad attendees.

For another Surrealism exposition in Paris, Duchamp designed a deluxe edition of a catalogue for the show covered with a breast. It took the form of a cast he made of the bosom of artist Maria Martins, and it was crafted of foam. As Filipovic tells it in The Apparently Marginal Activities of Marcel Duchamp: “Fellow artist Enrico Donati suggested using what was colloquially called a ‘falsie’—a store-bought foam rubber breast employed by women to pad their bras—and he apparently also helped convince a Brooklyn-based manufacturer to make a batch based on Duchamp’s plaster cast model. The two artists then hand-painted the nipples of each of the spongy breasts and attached them to a backing of black velvet … Hence, the body of Duchamp’s lover became the model for industrially made replicas that were, in turn, individually hand-painted to eventually become a series of artistic originals.” In addition, the back cover of the book bore a message for the reader: “Please touch.”

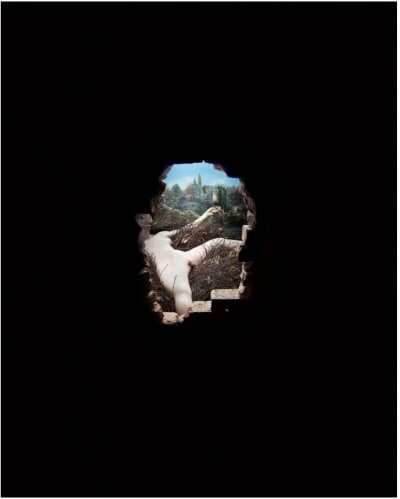

Before he died, no one knew that Duchamp had been working for 20 years on his still-elusive installation Étant donnés, which lives behind a large wooden door at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and is viewable only by way of two tiny peepholes. The scene that one sees offers a lot to get lost in: a forest’s worth of miniature trees, an illuminating gas lamp that flickers, an iridescent waterfall. Then there’s the naked body of a woman splayed out in a manner that evokes Gustave Courbet’s storied pelvic painting The Origin of the World. Duchamp donated the work posthumously, and nobody has known exactly what to make of it since. In her recent book, Marcel Duchamp and the Art of Life, Jacquelynn Baas compares its wry mix of mystery and kitsch to that in the art of David Lynch and Thomas Kinkade, while also suggesting that Étant donnés “might be a message from another planet.” Julian Jason Haladyn, in his sustained engagement of it for the Afterall Books “One Work” series, comes clean about authorial confusion at the start. “I should be straightforward at this point and tell you I have no intention of answering the question of what Duchamp was thinking by adding [Étant donnés] to his oeuvre,” he writes just a few pages in. “Such an exercise would be futile.”

Marcel Duchamp, Coffee Mill, 1911.COURTESY TATE MODERN

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, 1912.COURTESY THE PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM OF ART

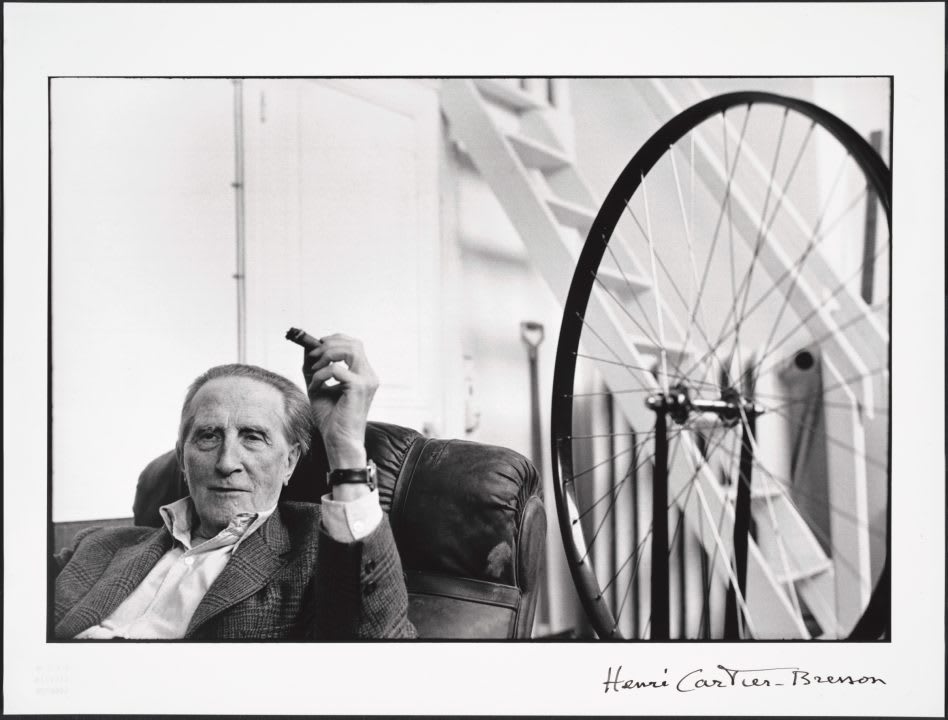

Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel at Barbican Gallery in London.TONY KYRIACOU/SHUTTERSTOCK

Marcel Duchamp, 3 Standard Stoppages, 1913–14.COURTESY TATE MODERN

Marcel Duchamp’s Comb, a promised gift of Barbara and Aaron Levine to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.COURTESY HIRSHHORN MUSEUM AND SCULPTURE GARDEN.

Alfred Stieglitz’s photograph of Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain as reproduced in The Blind Man, a promised gift of Barbara and Aaron Levine to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.COURTESY HIRSHHORN MUSEUM AND SCULPTURE GARDEN.

Marcel Duchamp’s Hat Rack, a promised gift of Barbara and Aaron Levine to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.COURTESY HIRSHHORN MUSEUM AND SCULPTURE GARDEN.

Marcel Duchamp, T um’, 1918.YALE UNIVERSITY ART GALLERY

Marcel Duchamp’s 50 cc of Paris Air at the Museum Tinguely in Basel, Switzerland.GEORGIOS KEFALAS/EPA/SHUTTERSTOCK

Marcel Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q., a promised gift of Barbara and Aaron Levine to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.COURTESY HIRSHHORN MUSEUM AND SCULPTURE GARDEN.

Marcel Duchamp, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915–23.COURTESY THE PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM OF ART

Marcel Duchamp, Door: 11 Rue Larrey, 1927.

Marcel Duchamp’s Rotoreliefs, a promised gift of Barbara and Aaron Levine to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. COURTESY HIRSHHORN MUSEUM AND SCULPTURE GARDEN.

Bookbinding for Ubu Roi by Marcel Duchamp and Mary Reynolds. COURTESY THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO

Marcel Duchamp’s The Box in a Valise, a promised gift of Barbara and Aaron Levine to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

Marcel Duchamp’s 16 Miles of String in 1942. COURTESY THE PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM OF ART

Marcel Duchamp’s Prière de toucher, 1947. COURTESY SOTHEBY'S

Marcel Duchamp, Étant donnés: 1. La chute d’eau, 2. Le gaz d’éclairage (Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas, 1946–66). COURTESY THE PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM OF ART