On the Ins and Outs of Making Stuff

Lawrence Weiner and Kim Gordon

Geographically, Lawrence Weiner’s West Village townhouse isn’t that far from the South Bronx neighborhood where he grew up. But in the seven decades between then and now, the wily, wise, bearded, disputatious bohemian maestro has hung out with the Beats and the Abstract Expressionists; experimented in painting, sculpture, film, books, and even dynamite; and created what could be considered his very own genre of art production. That last and most famous achievement involves his energized text works: words, phrases, and sentences rendered in his signature capitalized typefaces. Since the late 1960s, these texts—sometimes long, sometimes short, sometimes shouting, some- times a soft parenthetical suggestion, always koan-like in their ability to break from routine logic—have graced the tops of buildings, wrapped around walls, embellished manhole covers, bounced around the cubes of galleries, and filled swimming pools. Weiner’s texts can sometimes feel like modest instructions and other times like a god’s holy orders; they often use natural imagery and just as often seem to be delving into the nature of time, order, and meaning; they have their roots in 20th-century urban sign painting but also in the foundations of etymology; they move, jump, circle, and zing like cartoons, but offer a sense of Zen transformation. Weiner has long been connected to an influential mid-20th-century art movement that celebrated process over product, and ideas over material entities, but call him a conceptual artist at your own risk. At 78, the artist and his language have not gone soft.

Earlier this year, Weiner unveiled a series of stenciled wall texts using the colors of the American flag—“IN THE WAY,” “ON THE WAY,” “ON VIEW,” and “REMOVED FROM VIEW”—at Regen Projects in Los Angeles. Last month, a series of ten aerial banners with words by Weiner in English and Italian were flown along the coast of Rome. Now the artist is at work on a number of upcoming shows, including a retrospective of his poster works in Vancouver and a museum exhibition in Denmark. His friend, the musician and artist Kim Gordon, called him during quarantine to talk about the ups and downs and ins and outs of his magnificent career. It seems wrong to print any of Weiner’s strong opinions in lowercase.

———

LAWRENCE WEINER: Hi there. Where are you these days?

KIM GORDON: I’m living out in Los Angeles. It’s sunny, despite everything.

WEINER: I’m still in New York and I’m hoarse.

GORDON: I first met you in L.A. And then, when I moved to New York around 1980, I looked you up and went over to your house on Bleecker Street. You had a loft there. And I remember being so impressed. I think yours was the first truly bohemian family I knew. It was really eye-opening for me.

WEINER: I’m glad. That means you wouldn’t walk into walls.

GORDON: I still carry around some of the things you said to me. Let’s start with this question: How do you arrive at the words and texts you choose? You’re associated with conceptual art, but for me, your work is more like a mix of Dada and shamanism.

WEINER: Oh, it’s not shamanism. There’s really no need for shamanism. I’ve never wanted to be a guru at all. I am really, genuinely, quite happy being an artist. If I can continue doing that, it would be enough.

GORDON: If you were starting out today, do you think you’d still be an artist?

WEINER: I would make art, but I’d have a different attitude toward the whole thing. I’d walk away from all the people carrying their university schooling and academic backgrounds with them. That’s not the art world I entered into in the 1950s and early ’60s. You didn’t need credentials then. Now, most art is based on credentials.

GORDON: Who were some of the artists around when you were starting out?

WEINER: [John] Chamberlain, [Donald] Judd, [Willem] de Kooning—they were all there. But I had already decided to make art when I discovered them. What kind of art I would make ended up being the issue.

GORDON: Did poets influence you?

WEINER: No. I liked poetry, but I was mostly interested in Abstract Expressionism because that was a sign of freedom for working-class people. The Abstract Expressionists believed that they really were going to change the world. They also accepted anybody’s work that they thought was interesting. They really didn’t care about the person. For example, you could be a fan of Ad Reinhardt without knowing whether he was on the left or the right. People were just looking at the work. I was attracted to the lack of exclusivity. The real difference was class, and it’s still the same in the art world today. Young people who don’t have to earn money to live have a different attitude toward the art world than those who have to earn it.

GORDON: That’s interesting.

WEINER: There were people like [Robert] Mangold, Dan [Flavin], and myself, who, if we could figure out a way to keep going, we were there. We didn’t waste any of our resources trying to keep people out.

GORDON: People in the art world who are successful tend to get comfortable and they’re not as willing to take chances, even politically.

WEINER: They’re not artists. Those are people who have decided that art is a profession. Art asks questions. It doesn’t have answers. And as far as being able to accommodate yourself, if you have a hotshot dealer, you have an easier time raising the necessary cash, but it doesn’t change the work.

GORDON: I never really expected to make money from music, and I still don’t. I mean, I’ve made a secure living from it.

WEINER: Nobody can make money from it.

GORDON: Well, some people can. But I’ve always felt like, “It doesn’t matter, I’m still going to do this.” Wasn’t conceptual art an attempt to take work outside of the art market?

WEINER: No, it was a bunch of schmucks. It was a bunch of people in universities who thought that if they could get together and have a department of conceptual art, they could be the boss. I think the conceptual art thing is ridiculous. I’m sorry if I’m sounding off about it, but let’s stop giving things classifications so that they can be taught in expensive schools.

GORDON: I agree. But I do feel that there were a lot of legitimate artists who came out of the 1970s who worked conceptually as a base. I’m thinking of people like Daniel Buren.

WEINER: Daniel is involved in the idea of a continuing conversation with society about the role of art. It’s not about art itself, it’s about the role of art. That’s not conceptual, that’s legitimate.

GORDON: I hate to keep using the word “conceptual,” because it’s so annoying to you. I feel the same way when people talk about “alternative music,” which is a radio-programming category. What about the graphic nature of your work? You use an incredibly sophisticated graphic system.

WEINER: That’s a necessity. It has to be presented visually so you have a choice: You can either wear a garbage bag or a dress. You have to wear something.

GORDON: Your text almost has a Dutch aesthetic in my mind. I wondered if there were any graphic designers who influenced you.

WEINER: No. Most of my graphic-design interests came about because I wasn’t satisfied with what was being presented to me. I would’ve just gone along, going into the tobacco shop, the stationery store, and taking what they had in classic letters in order to use them. And then I began to realize that things like Helvetica were evil. They were great things to begin with, and then they began to stand for legitimacy. The last thing I would like to do as an artist is stand for legitimacy.

GORDON: That makes sense. But I was thinking about the Dutch designer, Wim Crouwel, who did a lot of the catalogs for the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in the 1970s.

WEINER: Yes, I was attracted to Dutch typography that I had found in schools and museums in Amsterdam and Rotterdam. It was basically universal sans serif typeface, and I thought, “That’s fine. With that, I can say what I have to say, and it’s not related to the typeface.” A lot of people were able to copy what I did, and that’s good. That’s what art is for. Art is for people to use.

GORDON: How did you start making films?

WEINER: I didn’t want to write articles for magazines, and I felt that if I could make a film, I could place the kind of work that I do in a context that looks more amenable to me. And I knew how to do it, so I did it.

GORDON: I always think of filmmaking as collaborative.

WEINER: Oh, yes, I’m the luckiest person in the world. I’ve worked with Kathryn Bigelow, with Michael Oblowitz, with Gerrit Hilhorst. When you add it all together, I’ve really been quite lucky. That’s because people were very open in those days. They would just work with each other. The time is different now.

GORDON: Why do you think that is?

WEINER: I don’t know. I could make some lunatic statement that it’s a class war, and we let the wrong class in. But that’s nonsense. There is no wrong class and there is no right class when it comes to art, or science, or music. So I don’t have an answer for that.

GORDON: You were born in New York. But you first started showing in California, didn’t you?

WEINER: I showed a bit in coffeehouses in New York. But I had my first big deal, where I stood up and said, “Okay, shoot me down. Or don’t,” in Mill Valley, California, in 1960. I’m not a California person, but I was able to function in San Francisco. I don’t know why.

GORDON: San Francisco was a very working-class city at the time.

WEINER: Was it? I lived in the working-class area, so I don’t really know. It was fantastic. There were all these great people in the book business, in publishing, like City Lights and Discovery Bookshop. They were extremely open to people showing up. I got a job when I got out there. I had no connections. I knew nobody. Through a friend of a friend, I got taken in to help make sets for the theater.

GORDON: How long did you stay?

WEINER: Four or five months. Then I went back again, and stayed another four or five months. I don’t usually stay any place long. That was while I was “incepting” myself. That’s a nice word, isn’t it?

GORDON: What did the work look like that you were showing in coffee shops?

WEINER: Paintings.

GORDON: Word paintings?

WEINER: No, no, no. Painting paintings. Abstract Expressionist. A lit tle bit like Max Bill.

GORDON: How did you go from being interested in the Abstract Expressionists to using words as a form?

WEINER: That was a political decision. If you wanted to make something that everybody could get, the way to do that was to make something with genuine sculptural values and to portray it in a language so that people could be able to do it themselves. Not instructions. But something that sat by itself. So that was it, and it just happened.

GORDON: Do you see art as a primarily populist form?

WEINER: The funny thing is, people make art for other people. The vision is to have a concert, and when everybody comes out of the concert, they’re all whistling something. That’s not populist—that’s just giving somebody something they can use. And that’s why the work that I make is about giving the world something they can use. I always had to pay some attention to it because I had to pay my bills. My parents were very nice to me, but they were not successful.

GORDON: Did they support you emotionally?

WEINER: Emotionally, not at all. We’re talking about the ’50s. We’re talking about anti-communism, anti-intellectuality. Anybody who could read was called an “egghead.” My father worked in a grocery store. And later, he and my mother ran a candy store. I grew up in the South Bronx.

GORDON: Did you go downtown at all or explore other parts of the city?

WEINER: Of course. That was one of the reasons I had so many friends from the bars. I used to work nights unloading ships and freight trains. I’d end up at 3am downtown, on the west or east side. The bars then accommodated young people.

GORDON: It must’ve been an interesting time in New York.

WEINER: It was not bad. I wish I could say, “Oh, I fought my way up tooth and nail.” But I remember sitting at the Five Spot, listening to Coltrane and drinking beer. I could only afford one bottle of beer at the bar. When that was empty, I was expected to leave the bar to make room for somebody else. So I would hold onto that one bottle of beer until I felt like it was boiling in my hands.

GORDON: Wow. Coltrane. I wish I could have known New York then. I would have liked to have seen ’70s New York, too.

WEINER: The ’70s were not so bad as far as opportunities go. As far as money, that was something else. The only thing I can say is that before the art world was taken over by a certain class, it was much more open to people. Now it’s very closed. I listen to conversations. And when you’re listening to somebody who’s 30 years old ask somebody what school they went to in order to know if they can be friends with them, you just have to walk away. You can’t spend your time thinking about them. Those are not people, those are products. And art is not about products, it’s about people.

GORDON: It’s very different now.

WEINER: It is, and it will go back the other way. But now, with the virus, god knows what’s going to happen. I’m beginning to get bad feelings from people I know. They’re really frightened. Art’s not made by frightened people, it’s made by angry people.

GORDON: I feel bad for my daughter, who is 25. Maybe her life will be on hold for a year or two—

WEINER: No, it won’t. Her life will go on, I assure you. It’ll develop in its own way. I grew up in a place where everybody said, “There’s no way that it’s going to work. No musicians are going to come out of it, no artists, because it’s so frightening.” The South Bronx was like Fort Apache. Think about the artists who are out there now. They all come from things. It’s always very hard, isn’t it?

GORDON: What do you think about the mythology of an artist?

WEINER: Listen, everybody needs a bit of mythology in order to get laid. Every single person in the world— from the taxi driver, to the truck driver, to the artist, to the musician. But it’s not the point, and it changes every year. I don’t think my work entered into the world because of me. It entered into the world because of luck. It was the right time and the right place to be presenting it, and it was useful to other people. But it wasn’t because of any kind of mythology. I have a funny definition of art. Art is people who saw the configuration and were not satisfied with it and went to change the configuration of the way we look at objects.

GORDON: That’s a pretty good definition.

GORDON: Who are your favorite artists from the past?

WEINER: [Piet] Mondrian is my favorite. I learned so much from him.

GORDON: Another Dutch aesthetic. And I know you also lived in a houseboat in Amsterdam.

WEINER: I lived for 49 years, on and off, in New York and Amsterdam. The only reason I’m not in Amsterdam right now is that I have trouble, because of the cancer, getting on and off the boat. Other than that, I’m fine with Holland. It’s as flawed a culture as anyplace else, but it has its virtues.

GORDON: What was it that you were looking for when you were first looking at art and artists?

WEINER: Art is very emotional, at least it was when I entered the art world. It was a very emotional thing you were entering into. And the works that you were attracted to and the living artists you were attracted to were all about heartfelt emotions.

GORDON: That’s more how I feel about music than art. Art usually engages a different part of me.

WEINER: Well, the popularity that’s necessary to get art put out into the world is really the same as it is for music. You first have to get a stage, or else nobody will know about it. I hope I’m not coming across as too contentious.

GORDON: No, I don’t think so.

WEINER: Let me say that my contention and my problems are not with other artists. It’s with society itself. It’s not a competition. Sometimes you get stuck with these sort of middle-class artists, and they really think they’re in competition and they’re not.

GORDON: I’ve always seen it as more of a cooperation.

WEINER: It is cooperation with the culture, or a total absolute abnegation of it, a total hatred of a culture. A lot of good art comes out of that. And a lot of good art comes out of people who see freedom and light in things. I do like the Janis Joplin line, “Freedom is just another word for nothing left to lose.” It’s the truth. Nobody gets out of bed in the morning unless they have a political reason for doing it, just as nobody makes art or music or dance without it being political.

GORDON: Yeah, it’s social.

WEINER: It’s social. It’s for other people, exactly.

GORDON: I like Sartre’s line about freedom. It goes something like, “Anxiety is what freedom feels like.”

This article appears in the September 2020 issue of Interview Magazine. Subscribe here.

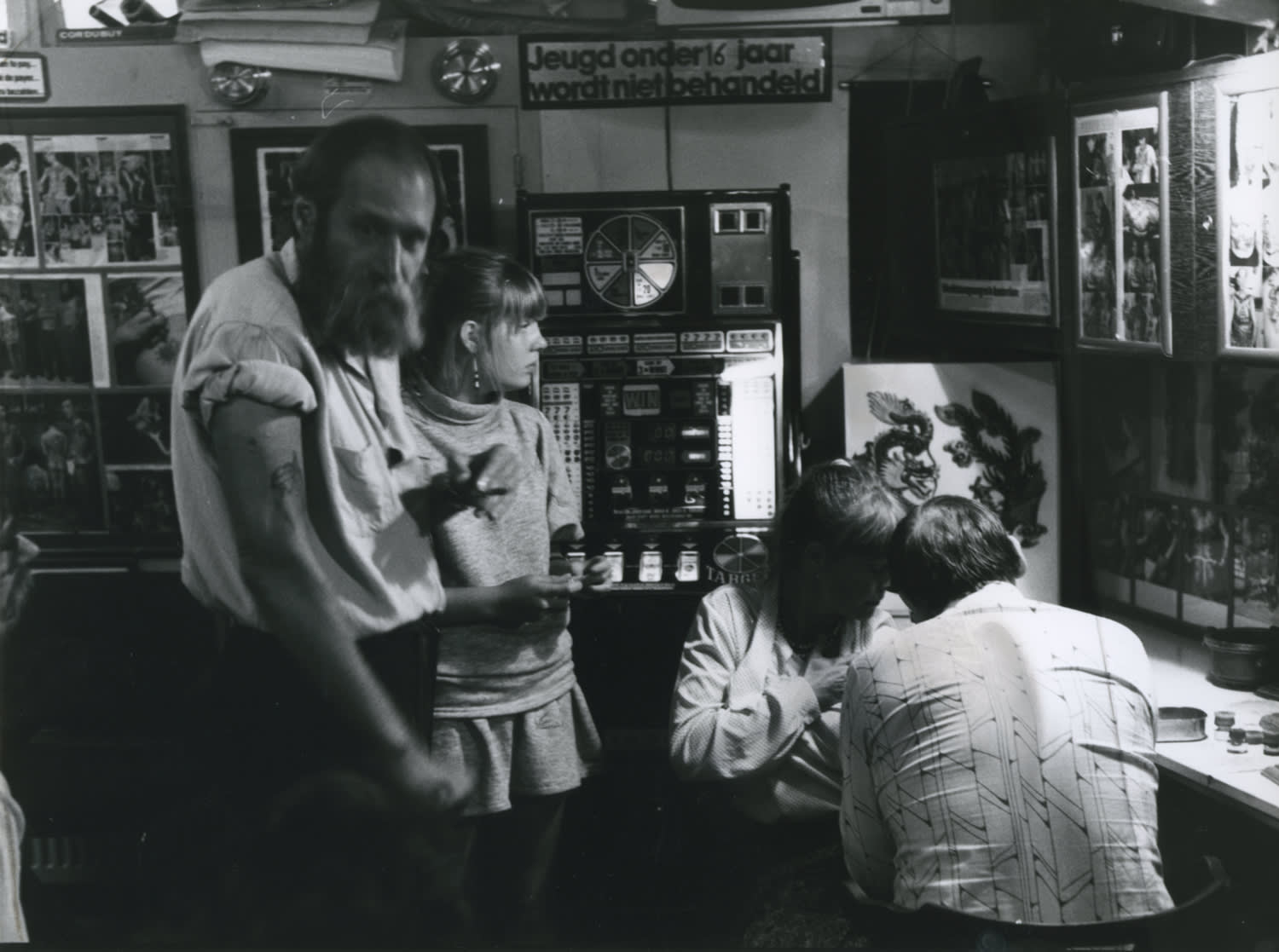

From left: Lawrence Weiner, Kirsten Weiner, and Alice Weiner at Tattoo Pete’s tattoo parlor, Amsterdam, after a day of shooting Weiner’s movie Plowmans Lunch. Photographed by Frank Vellenga, 1982.

From left: Keith Sonnier, Andy Warhol, Ed Ruscha, and Lawrence Weiner at Leo Castelli Gallery’s 25th Anniversary Exhibition, New York, 1982. Below: “On Top of the Wind,” Dvir Gallery, Tel Aviv, 2013.

Photography Matthew Tammaro

Photography Matthew Tammaro

“Right on Top,” Regen Projects, Los Angeles, 2002.

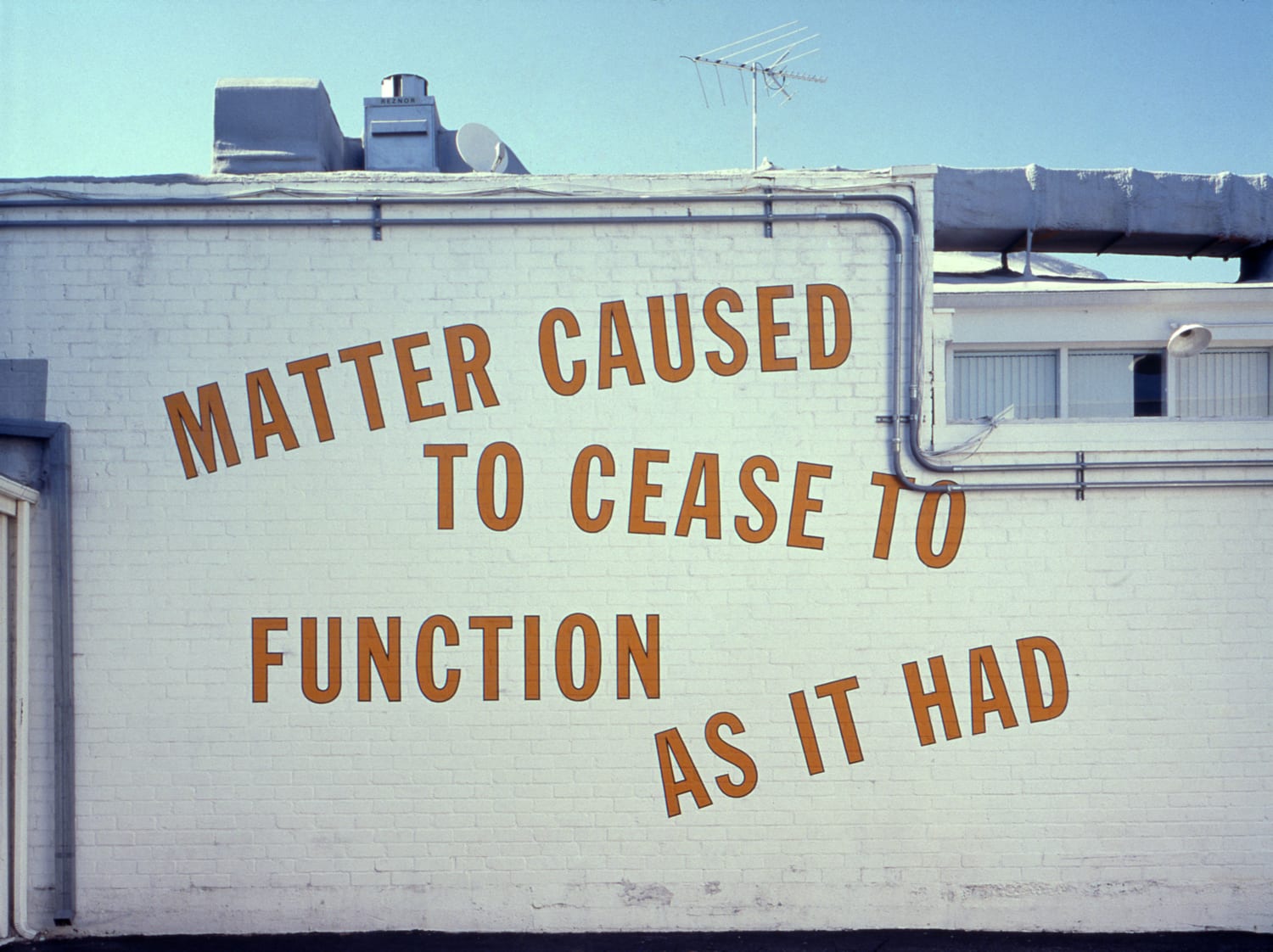

“Matter Caused to Cease to Function As It Had,” Courtyard of Regen Projects’ former West Hollywood space, 1995.

Artwork and Archival Images: Courtesy LAWRENCE WEINER, MOVED PICTURES ARCHIVE, NEW YORK, and REGEN PROJECTS, LOS ANGELES