Cory Arcangel: LOL, TBH

Cory Arcangel’s voluminous post-media output runs the gamut from a book and an LP to noodles and repurposed video games—but is he just being ironic? The Brooklyn-based artist discusses humour and honesty with Ariela Gittlen.

Cory Arcangel’s Brooklyn studio is tucked away in a former warehouse and shipping complex, between an elevated expressway and a strip of docks thrusting westwards into the Hudson River. While the building is impossible to miss, the studio itself is well hidden, and I become lost in a warren of identical hallways, each leading instead to a woodworking studio, an obscure startup or an artisanal chocolate company.

Arcangel’s studio, when at last I find it, is small, spare and calm. It’s the sort of room where it’s easy to imagine several people tapping at keyboards in companionable silence. The major attraction is about twenty pool noodles (those colourful cylinders native to suburban swimming pools), which lean against the wall, waiting to be fully dressed and then shipped to exhibitions in Milan and Bergamo. Some are wearing Aero or Gap branded sportswear, tailored to their noodley dimensions. One is listening to Disney’s Frozen soundtrack on her iPod, another is dressed for a job on Wall Street.

“They’re funny,” Arcangel admits of the series collectively titled Screenagers, Tall Boys and Whales (2011–14), “but hopefully in fifty years people will see them and get a real sense of what it was like— the fashion, the style and the social dynamics of what it was to be alive right now.” He gestures to a black-clad pair in the corner. “These two are goths.”

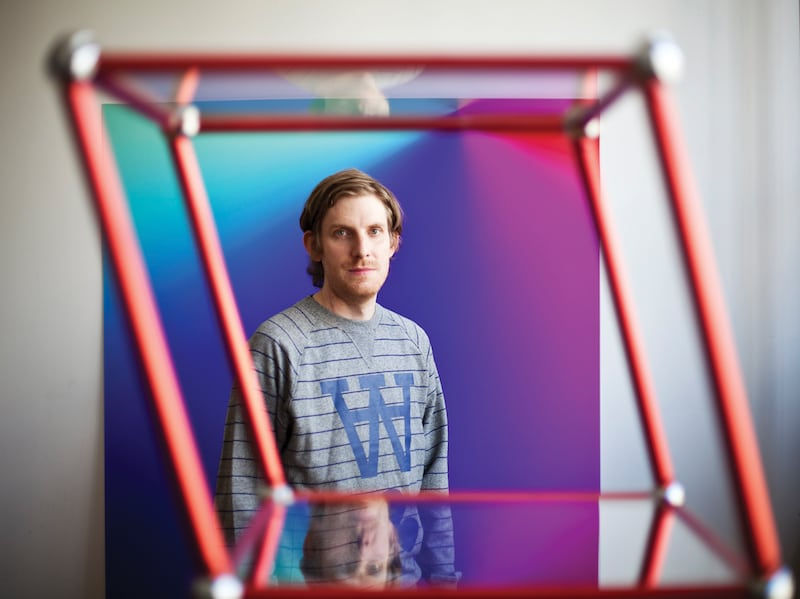

In 2011 Arcangel was the youngest artist since Bruce Nauman to have a solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and at thirty-six he is still boyish and floppy-haired. One of the first artists to be widely recognized for embracing video games, websites and software, Arcangel became known for video-game modifications such as I Shot Andy Warhol (2002) (the eponymous artist is substituted for the usual baddies) and Super Mario Clouds (2002) (everything is removed from the game except for its drifting clouds).

“Now more people have the language to understand, because we’re all on computers every day”

Currently, he creates work in a wide range of media, including video, music, computer code, performance and the internet. He recently published a book made up entirely of tweets (Working On My Novel), recorded a rock album—really a transcribed conversation between friends masquerading as an LP (Rock$ by Title TK)—and created a film about surfing a website (Freshbuzz [subway.com]). He also orchestrated a collaboration between organisations as disparate as the Carnegie Mellon Computer Club and the Andy Warhol Museum, which culminated in the discovery of several of Warhol’s never-before-seen experiments with digital art.

Arcangel uses digital media to explore its rapidly expanding role in our daily lives. Like Warhol, he appropriates, disrupts and recycles popular culture. His Campbell’s soup can: the internet. Although much of his work begins with humour or play, it rarely ends there. What seems straightforward at first often abounds with complexity. It may lead to an exploration of a hidden system, a meditation on melancholy or an artisanal chocolate company.

What does the term “post-internet art” mean to you?

I get this question all the time lately, it’s so insane. It used to be you couldn’t make anything that was less cool. People in the fine-art industry really disliked work that dealt with technology. So for there to be such a rapid shift, I still am completely disoriented. It just proves you can never really know. The world is a strange and mysterious place. God, when I used to show curators websites I made their eyes would just go blank. I could see that they were thinking, ‘Please stop showing me this, this is not interesting.’

They would recoil?

Yeah, it was just a different generation. But anyway, that’s just an aside. I took a couple of years out in 2012–13. I didn’t show any new work and I just muddled around. I remember that internet people started asking me, ‘What do you think of the new aesthetic?’ At the same time art people would say, ‘What do you think of post-internet?’ There were two terms for two different groups of people who were both trying to get at the same thing. Have you heard that term, the “new aesthetic”?

Yes, I’ve heard it in the context of graphic design as well.

For me it means a new generation. It’s all the kids who were in art school and graphic design school when the internet was part of their real lives—it wasn’t a niche weirdo thing any more. And then all those kids graduated, and now they’re making work that has yanked the dialogue in that direction. What is the cliché? It couldn’t have come any sooner? If it would have been any longer I would have gone crazy.

“God, when I used to show curators websites I made their eyes would just go blank. I could see that they were thinking, ‘please stop showing me this, this is not interesting’”

The art world finally caught up with what you had been doing?

Well, not just me, but all the net artists and the different communities that I participated in for the past fifteen years, because there was lots of people were making work that dealt with technology and networks and net art. Net art has been around for twenty years.

Well, since…

Since the beginning of the internet. Now more people have the language to understand, because we’re all on computers every day. Even my mom and my aunts are on computers all day. Everybody now has the capability to understand the work, whereas in the nineties it took a lot of expertise to understand what these artists were doing.

Your website certainly has a point of view. (Laughs)

Yeah, my website doesn’t look it, but it’s overly theoretized. I always like my website to be six or seven years behind the times.

It feels nostalgic. The aesthetic reminds me of Geocities and Myspace pages from the late 1990s and early 2000s—like something from that amateur era of web design before everything became so polished and corporate.

Which means I need to redesign it. My website should not be nostalgic yet, it should make you sick. My website is a little out of date in terms of my sweet spot for being out of date. The design is actually from a Quicken small business template. You could actually buy web templates from them years ago. My site is like a slightly misguided mom and pop [business website] circa ’05.

But the web certainly went through a shift from that golden era, which for me was the nineties, when everything had to be built by hand. Conceptually, I don’t believe in hierarchies of eras. It doesn’t make conceptual sense that one era is better than the other because everything is always okay. How could one era be better than the other? Disregarding catastrophes of humankind. In the cultural realm there’s always good young artists but, that said, my intuition has trouble getting over the amateur era of the web. I’m like one of those people who only listens to hip-hop from the eighties. For me that era was really special. My website is in that continuum. It’s somewhere in between today and then. I spend too much time on it, it’s ridiculous because no one goes to it any more. People don’t go to websites, they just go on Instagram orTwitter. You post something on your webpage it’s like yelling into a cave.

“The internet was part of their real lives—it wasn’t a niche weirdo thing any more.”

What draws you to the obsolete machines and computer programmes that are often part of your work?

It’s something about mucking around in old stuff. It’s a treasure hunt, that’s what I like about it. I can’t quite explain it, but as soon as some- thing becomes no longer relevant then all of a sudden I’m interested in it.

It strikes me that there’s a kind of animism— imbuing objects with souls.

Definitely, I believe that. I’m down with that.

You reminded me of Marie Kondo’s book that’s gotten so popular: The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying.

I’ve heard about that. What does she say to do? Throw everything out? Or not throw everything out?

What you do is this: go to your closet and empty it all on to the floor, then hold each object in your hands and decide if it brings you joy.

Oh man, that’s awesome.

And if it doesn’t, you thank it, and you let it go.

I love it! I love it!

The way you talk about these obsolete machines—

Things that bring me joy. I have storage unit across the street filled with stuff that brings me joy, so her method would not work on me. For me the problem is digital stuff. So much digital stuff weighs me down. I don’t know what to do about that.

I don’t completely trust any method of digital archiving.

The only thing you can trust are things like my sourcecode zines. Each of them is a different source code for a [digital] project, which is footnoted and printed on archival painter. They’re my back-ups. That’s the only way to do it. Seriously.

What if there’s a fire?

I’m giving them to different people and selling them online and they’re dispersing all over the world. So, literally the world would have to end. (Laughs) Which, of course, is coming.

“It’s something about mucking around in old stuff. It’s a treasure hunt, that’s what I like about it”

One thing that’s compelling about your work is the tension between humour and boredom. In your film Freshbuzz (subway.com), you surf the Subway website…

I do.

… for an hour. What happens after you pass through amusement, you get to boredom—and then what? What’s the goal?

I can tell you an aside about that. We screened it at BAM [The Brooklyn Academy of Music], and it turned out to be shockingly entertaining.

Why wasn’t it boring?

The communal experience combined with the audience seeing everything for the first time. Those screenings, weirdly enough, turned out to be not what I was hoping, which was this kind of drawn-out boredom. You know when the plane breaks the sound barrier there’s some weird thing that happens where, right when the plane gets to the speed of sound, there’s an explosion or some shit? There’s some kind of [claps loudly] and then you’re going faster than sound. There’s a similar thing that happens when you break out of your daily nonsense—your thoughts, wanting to check Instagram, and the itch to do this and that. With these kind of works that deal with duration and maybe boredom, there’s a certain point when you hit that sound barrier and something weird happens, you relax and submit and you see things new again. I’ve found you really do have to force people into it. That’s why screenings are good or concerts are good; these kinds of concentrated situations.

People sometimes accuse you of being ironic.

Yeah, people often think that the work is ironic, or just a joke. My thought is that I’ve dedicated my life to this and I can’t be dedicating my life to being ironic. These things are very dear. They seem like a joke at first, but it’s never what they are. If you look at them they’re always a little bit more complicated. Comedy is like that, right? You see a good comedian and he’s doing magic on stage. He or she is revealing this stuff that you can’t believe they can reveal so succinctly and so efficiently. Comedy to me is the top of the heap.

The highest form of art?

Yeah! A comedian will slowly lead you in one direction, then say something and [clap] every- thing will change.That’s what I hope my work is. It deals with time in a different way and it’s in a different space, but there is hopefully real truth and something honest about what it means to be human in all of it. I wouldn’t have spent three years on Working On My Novel if I thought it was just something funny. There has to be something true in it.

An interviewer described your work as being about that tension between success and failure.

Maybe melancholy. Most of the work is melancholy actually. I think almost all of it is, no?

The photographs from the Photoshop Gradient Demonstrations series are so big and bright, they seem celebratory to me.

Let me just put it this way: I could tell you what I think I’m doing, or what I’d like to do, but it’s never really what the work is. It’s shocking to me how little I know. Any artist who says they know what they’re doing is full of shit. That’s me paraphrasing Duchamp, but anyway.

The Photoshops were also interesting because that has a lot to do with institutional pressure. What it means to be on the wall, what it means to be that size, what it means to be part of that history. They are readymade; I’m just filling in a blank space with the paint bucket. So I also see them as a bit melancholic: this space needs to be filled, let’s just use the paint bucket. They are successful, I think, because they do go both ways. People see them and they’re like, ‘Woah!’ Maybe the experience and the concept are at odds with each other.

The Photoshop Gradients are readymades, but when you see them in that net-art context they start to resemble the colour-field paintings of high modernism work that took originality so, so seriously.

Yeah, totally. LOL.

LOL.

TBH. I heard that teens will say ‘TBH’ after everything that they type now.

What does that stand for?

To Be Honest.

Well, if you don’t write it, how do I know you’re being honest?

You can put it in after every sentence.

I absolutely will.

Your Performance, 2015. Photo: Jack Hems

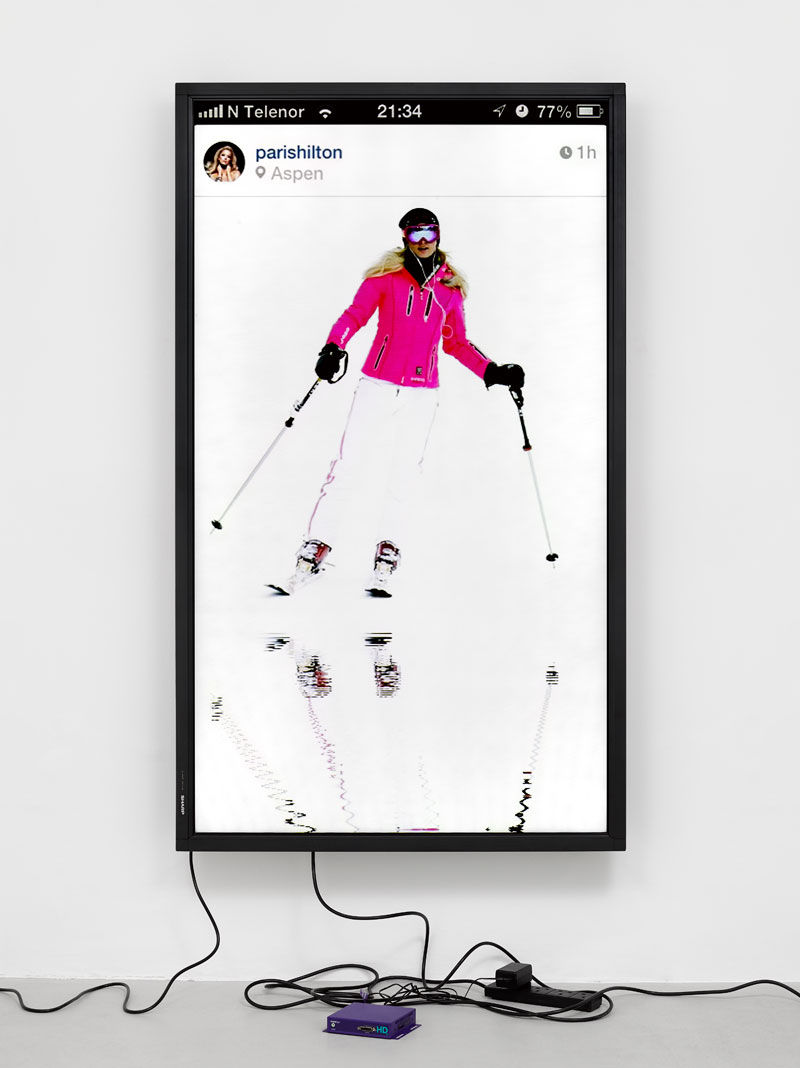

Snowbunny/Lakes, 2015. Photo: Jack Hems

From the Photoshop Gradient Demonstration series, 2014

From the Photoshop Gradient Demonstration series, 2014