Because it is continuously evolving and shifting shape, Imi Knoebel’s abstract art eludes easy description or categorization. Born in Dessau, Germany, in 1940, Knoebel makes playful, fearlessly experimental paintings, sculptures, installations, and works on paper that range from spare to multiplex and geometric to freeform, occasionally in the same work. Although they include a wide range of other materials, their primary ingredients are painted wood panels. Often fitted with bare wood skirts at their perimeters, they stand proud of the wall or are shaped, stacked, or abutted, blurring distinctions between two and three dimensions. Everything the artist makes is free of recognizable imagery, except a series from 1970 in which he used tiny dots of white paint to add an additional star to photographs of galaxies and a handful of projects incorporating found objects or photographs. Knoebel’s works have been called minimal, hard-edge, and eccentric abstraction, but all of these terms fall wide of the mark. As one curator noted, words “simply roll off their surfaces.”1

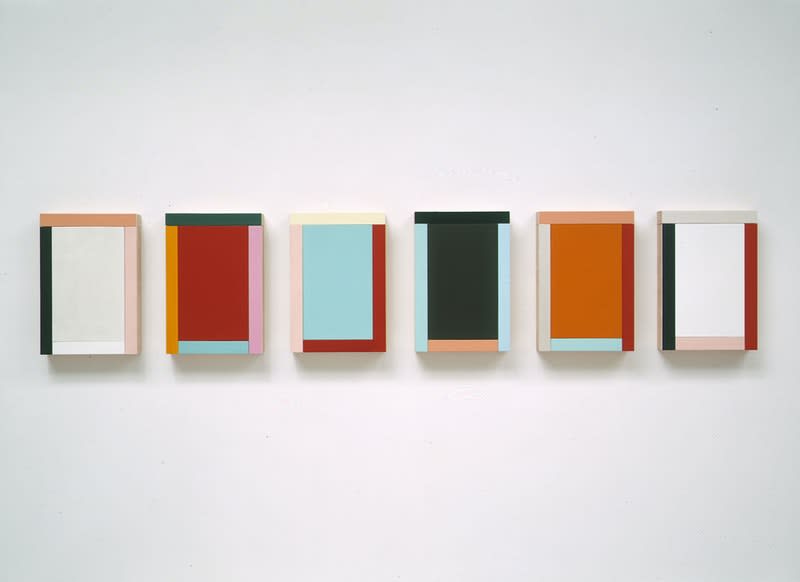

A number of hallmarks unite Knoebel’s strikingly diverse body of work. Among them are surprising colors and forms, bravura brushwork, and impeccable details—especially around edges. For example, the six 19 11/16 × 13 5/8-inch, acrylic-on-wood paintings composing Grace Kelly III 1-6, 1994, consist of a vertical panel surrounded by four flush-fitted, square-section bars, the deep sides of which are left unpainted. These sections are arranged so that those on top overlap the sides and those on the bottom rest between them. Each of these individual components is covered in even, lengthwise strokes of different soft, dusty hues, including yellows, blues, reds, pinks, and browns. These colors circulate throughout the group, moving from middles to and around margins and joining new shades in each component painting. In doing so, they create a subtle dance of change and iteration. As its wryly evocative title suggests, the work calls to mind the beguiling pastels of the American actor’s classic Technicolor films. It also recalls the dynamic equilibriums of Piet Mondrian’s rectilinear designs and something of the look and feel of macarons, confections the artist’s daughter bakes at her pastry shop. First and foremost, however, Knoebel’s works foreground their own formal devices. When not strictly descriptive, their names, given after the work is completed, hint at Knoebel’s life and enthusiasms but also serve as oblique reminders to his viewers to use their own creative powers to find ways into and out of their resplendent self-containment.

Asking, famously, “What can I say that my works don’t?” Knoebel is renowned for his reticence about and indifference to the rhetoric surrounding his work.2 In his career, he has given only a handful of on-the-record interviews, most of them to his friend and classmate at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in the late 1960s, artist and activist Johannes Stüttgen. In person, however, Knoebel, a trim man with an elegant mane of brushed-back white hair and alert, bespectacled blue eyes, is friendly and open. He is happy to discuss his interests and methods, which are as eclectic and original as the things he makes.

We meet in the kitchen of the artist’s spacious, tall-ceilinged townhouse in central Düsseldorf for an afternoon of conversation. Knoebel’s wife Carmen, his longtime manager and former proprietor of the city’s legendary art and music bar Ratinger Hof, joins the discussion. So does Stüttgen who, with Knoebel, was a student of the legendary artist, activist, and educator Joseph Beuys in the late 1960s and today works to promulgate his professor’s belief that each individual must envision a communal future based on creativity. Carmen gives a precise overview of her husband’s career. Stüttgen, who has written extensively on Knoebel’s work, serves as an expansive, cosmically oriented foil to the laconic, down-to-earth artist. What follows is a reconstruction and interpretation of the conversation in German from memory and handwritten notes.

Stüttgen begins the conversation by proposing that Beuys’s Wärmetheorie, or theory of heat-energy is key to understanding Imi’s art: “There is a warmth, a presence in Imi’s work that draws the viewer in.” He also throws out the theory that global warming is nature’s response to humanity’s inner coldness. Knoebel listens intently but says nothing. He too is a product of his time with Beuys, but he took a different path through the professor’s class—one grounded in the fundamentals of working in the studio.

“I was studying at a very boring, Bauhaus-inspired school of applied arts in Darmstadt and wanted to get away,” he says. “Luckily, I had a great friend and collaborator in Imi Giese (1942–1974).” (Their shared first names derived from their habitual greeting, “Ich mit ihm,” or “I with him.”) “Together, we discovered a host of things that inspired us. One was the music of free-jazz musician and composer Ornette Coleman. We would follow him on tour. Another was the art of Kazimir Malevich and his Suprematist movement. Both seemed radical and extreme.” Discoveries like these pointed to a way out of their conventional paths for the young artists.

In 1964, the Imis saw the now-famous photograph of Joseph Beuys leaving a Fluxus festival in Aachen with a bloody nose after being assaulted by an angry audience member. They knew they had to go to him—“to feel his presence, his aura—to become disciples . . . perhaps in the Buddhist sense that the student must seek out the teacher,” Knoebel says.

Malevich was their ideal of a radical, revolutionary artist; Beuys was a real, contemporary example. Originally enrolling in the graphic art department at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, the pair, who with their shaved heads and workers’ overalls, resembled the Russian revolutionaries they so admired, petitioned Beuys to take them on as students. “We had nothing to show him but said we would do great things as his students.” Without hesitating, Beuys gave them the keys to Room 19, a studio adjacent to his legendary classroom Room 20. He gave the Imis one year to prove themselves.

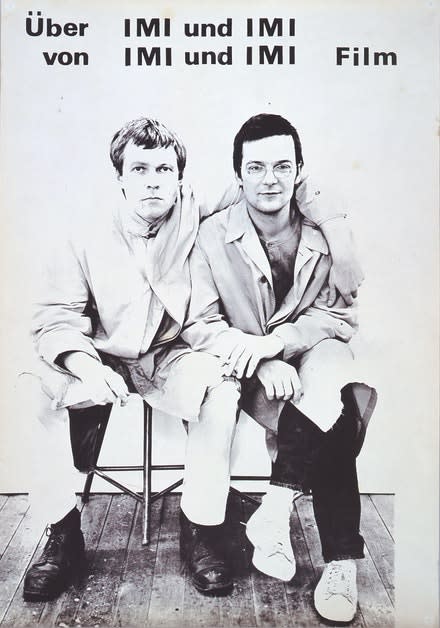

“Once Beuys took us on, we sat at a table in Room 19 wracking our brains about what to do,” Knoebel remembers. We had no idea where to begin. Thankfully, Imi [Giese] had the courage and presence of mind to make a start. He started poking holes in sheets of paper with the needle point of a compass. I started drawing straight lines with a pen. Imi was my greatest influence. He drove us to follow our interests and put them in motion.” Although they were close, the Imis collaborated only a few times, most notably on a “film,” Über IMI und IMI von IMI und IMI (About Imi and Imi by Imi and Imi). It ran only in real time and real life in the form of the duo’s carousings at the Intermedia festival in Heidelberg in 1969.

It was through their projects in Raum 19 that the Imis met Stüttgen. Prominent in the freewheeling, philosophical Ringgespräche (discussion circles) in Beuys’s Room 20, Stüttgen wondered what the Imis’ rudimentary, repetitive activities had to do with their teacher’s expanded concept of art. Imi and Imi were headstrong, he says, expressing little interest in the artistic theories or provocations that were the order of the day at the Kunstakademie. Yet Stüttgen felt a deep resonance with the artists. He describes them as his “bodyguards,” warmly supportive colleagues who always attended but never participated in his talks. Later, after watching Knoebel make thousands upon thousands of line drawings that eventually were enclosed in five filing cabinets in the work 250 000 Zeichnungen (250,000 Drawings), 1969–1973/75, Stüttgen had a revelation: the duo had instantiated Malevich’s concept of “liberated nothingness.” They had made manifest the Suprematist idea of an art apotheosizing pure feeling over representation. He would later celebrate Knoebel and Giese’s artistic search as a grand redemption of modernism:

It was the total impaction of the total demand of an all-inversive art that was substantiated by nothing other than itself: the ‘image of imagelessness,’ the ‘liberated nothingness’ (K.M.). Everything was suddenly clear; nothing else would ever be valid. And all at once this validity was doubly valid: The ‘liberated nothingness’ liberated the nothingness of two men in waiting. Nothingness encounters nothingness! A path was initiated. Nothing else existed except the black square and its demands. Not talent, none at all, at least not of the type that would matter here, only the certainty of this will; this self-consciousness without end that is initiated in nothingness, the pure bliss of two I(s), two ‘Imis’, literally two good-for-nothings, who are ready to do anything, who are extricated, and who are now waiting for their chance… . They had very tangibly gotten ahold of nothingness 3

In fact, Knoebel would take on Malevich’s 1915 milestone of abstraction and abnegation, Black Square, in his own large painting Schwarzes Kreuz (Black Cross), 1968. This work consists of a long black rectangle bisected perpendicularly at its midsection by a shorter bar and hung canted to the right. Swiss curator Konrad Bitterli regards this leap into the three-dimensional pictorial space of a panel painting as a logical conclusion of the two-dimensional line drawings. He also calls the homage to the Russian Suprematist a “secularization” of the crucifix and an emblem of the “programmatic process of emptying” defining all of Knoebel’s nonobjective art.4

Later in 1968, Knoebel would use this classroom to create the eponymous, career-defining sculptural installation Raum 19. Infinitely reconfigurable, it consisted of 77 components made from raw spruce and flat and curved panels of Masonite—boxes, right angles, cylinders, and panels. Full of potential and mystery, this collection of ghost shapes created a veritable warehouse of ur-forms that the artist would reconsider and recreate throughout his career. Masonite, an inexpensive processed-wood material popular after World War II, became an important and oft-recurring material in Knoebel’s work. It was vastly underappreciated, he believed, especially for its smooth and warm brown surfaces. A later version, Raum 19 III, 2006, is augmented by Batterie (2005), a boxlike structure made of aluminum panels painted phosphorescent green. As it glows in the dark, it testifies to the work’s abiding power in his oeuvre and recalls Beuys’s energy-transfer theories. Where most of his contemporaries were grappling with the ramifications of May ’68, Knoebel occupied himself with the most basic formal and structural concerns: measurement, proportion, craftsmanship. Given physical form in Raum 19, these foundations, rather than any overarching vision, provided Knoebel’s creative spark.

Of course, Düsseldorf in the 1960s was the headquarters of the Zero Group. This international consortium of artists was looking for an aesthetic ground zero after that century’s catastrophes. Knoebel knew the work of Lucio Fontana, Yves Klein, and other members but says they “floated above the ground.” His head, he admits, was filled with wild ideas, but he resisted the totalizing statements of members like Otto Piene, who said the group was questing for “a zone of silence and of pure possibilities for a new beginning as at the count-down when rockets take off.”5 Instead, Imi and Imi styled themselves as the workers at the academy. They grappled with the ineffable as a tradesperson might, using everyday materials, handicraft, and their own powers of discernment. For this reason, Knoebel always called himself a “painter.” He was grounded in his materials and their power and potential—in contrast to the Zero Group’s transcendentalism and Beuys’s utopianism.

Like his contemporary, American process artist Richard Serra, Knoebel developed a form of autopoiesis by letting the process of working with materials and forms in the studio drive his artistic program. But where Serra and Minimalist sculptors like Donald Judd with whom he was associated emphasized industrial materials and fabrication techniques, Knoebel took a more lyrical, craftsperson-like approach. Naturally, given his prolific practice and the scale of his works, Knoebel employs a team of skilled technicians. However, they work shoulder-to-shoulder with him, supporting and amplifying the scope and reach of his tactile, investigative methods. This open, human factor, plus the fact that the artist’s hand enlivens all stages of the process, provides much of the warmth that Stüttgen described at the beginning of the conversation.

In Stüttgen’s conception, Knoebel arrives at a form of pure abstraction through a process that is elemental and warm-blooded. He calls Knoebel’s approach “thinking without thoughts,” an idea the artist has affirmed, saying,

When I am asked about what I think about when I look at a painting, I can only answer that I don’t think at all; I look at it and can only take in the beauty, and I don’t want to see it in relation to anything else. Only what I see, simply because it has its own validity. 6

Steadfastly nonrepresentational, Knoebel’s works, whether manifestly material like Raum 19 or approaching immateriality like the line drawings or his 1968 light projections from a moving vehicle onto city streets, are grounded in lived experience in ways that the work of his more rigid and procedurally oriented transatlantic counterparts are not. They are, Stüttgen says, the products of Knoebel’s personal, hands-on search for art’s highest and purest forms. As such, they must follow the dictates of this quest, wherever it takes the artist. On this and all topics regarding what his work might represent, Knoebel is silent. Declining to engage in any discussion of the transcendent power of abstraction, he answers a question about his experience of visiting the Rothko Chapel in Houston with Palermo in 1975 with a laughing “Americans pray too much.” He and Carmen would rather discuss Niklas Luhmann’s system theories, Jaimie Branch’s jazz trumpet, or Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Holger Czukay’s rock ‘n’ roll. He does, however, admit his undying love for the visual force of Rothko, Pollock, Newman, and the greats of American postwar abstraction.

This is not to say that Knoebel’s method is entirely spontaneous. The walls of a room in his capacious, multi-story studio in a former architectural detail factory are covered with many hundreds of samples of colored construction paper that that he selects from to make his “Messerschnitt” (“Knife-Cut”) collages. The jagged, curvilinear, and polyhedral shapes filling in these serve as repositories for future forms and hues and relate directly to the stained-glass windows he designed for France’s Reims Cathedral, the only commission he has ever accepted. His practice of letting colors and designs incubate stems from the artist’s memories of discussions with his friend, painter Blinky Palermo. In 1975, Knoebel wanted to move beyond his predominantly black-and-white palette and use a green but could not decide which, so he drew Palermo, a renowned colorist, into a months-long quest for the perfect shade. His compatriot’s death in 1977 prompted Knoebel to embrace vivid color in the 24 Farben-für Blinky (24 Colors-For Blinky), a memorial group of large, shaped acrylic-on-wood paintings of the same year, in the collection of DIA. Resembling spikier and chromatically higher-keyed versions of Ellsworth Kelly’s shaped canvases and wall reliefs derived from sense memories, Knoebel’s abstractions commemorate an artistic friendship forged through a deep, shared interest in the relationship between color and form.

Scale models and plans for the artist’s periodic stock-taking installations also dot the studio. As counterpoints to the regular, serial method by which he develops new motifs, Knoebel also assembles and displays groups of objects based on past and current ideas. These mini self-surveys give Knoebel space to reappraise and reenergize. For example, the museum-scale Kernstücke(Core Pieces), 2015, contains 21 parts inspired by new and old bodies of work. Each part of Kernstücke represents a key idea from the artist’s past series or the one-off Zwischenwerke, or “In-Between Works,” that crop up outside of them. And each of its components, although inseparable from the whole, is given a unique name and one or two dates, depending on whether the year it was made differs from that in which its concept was first developed. Occasionally, too, Knoebel makes multipart and room-scale installations as memorials. 24.1.1986, 1986, named for Beuys’s death date, uses lengths of metal pipe, found wood, and a bare tree trunk standing in a found-wood box abutting a closed, rectangular Masonite structure to commemorate the alchemical powers of his teacher. Eigentum Himmelreich (Property of the Heavenly Kingdom), 1983, remembers the tragically short life of Knoebel’s early artistic doppelgänger Imi Giese through a wide variety of found, constructed, painted, and assemblage-d objects, including the ladder his friend used to hang himself—each of which suggests order or chaos.

Stüttgen sketches a torus to diagram his conception of Knoebel’s method. The artist starts with nothing but his own selfhood—the hole in the donut—and proceeds from there until he makes something he knows will appeal to his audience and thereby function in the real world—the outer ring. Drawing arrows suggesting a continuous infolding, he illustrates a feedback-continuum of subjectivity and objectivity. Through a material object, an abstract work of art, Knoebel establishes a direct connection between subjects, between maker and perceiver. Stüttgen also graphs the cursive word “ich,” or “I,” which is not ordinarily capitalized in German, with directional arrows paralleling its letters and landing back on the dot of the “i.” As in the secret extra star he added to his 1970 Sternenhimmel (Starry Sky) photographs, Knoebel’s art begins and ends with this tiny “ego point”—an immaterial locus from which anything can materialize. (He also points out that “ich” forms the heart of “Nichts,” German for “nothingness.”) Similarly, Stüttgen believes that the “Sandwich” paintings conceived in the early 1990s, consisting of plywood panels separated by a layer of paint visible only where it drips out along the edge, are key exemplars of the artist’s inside-to-outside-to-inside methodology: “It is no coincidence that Imi’s birthday is December 31. Every ending is a new beginning.” Knoebel’s genius, he believes, is knowing when his subjective process will result in something objectively good and internally valid. Thus, Stüttgen asserts, the artist’s work exists in Lebenszeit and Weltzeit—in life time and world time: it is personal and universal.

For this reason, Stüttgen claims that Knoebel is the “last modernist”:

Malevich’s Black Square obliterated the image; Duchamp’s Fountain of 1917 opened up the entire world to art; and Beuys’s expanded concept of art posited that life itself could be an artistic act. When he arrived at the Kunstakademie, Knoebel knew that everything had been done. What Imi and Imi were doing at the Kunstakademie in 1964 was looking for a beginning, pondering the question ‘what do I want to be?’ In a time of aesthetic exhaustion, Knoebel is free precisely because he doesn’t know what to make. He goes into the studio each day searching for a beginning through his work. It’s a matter of zero versus one. When you’re looking for a beginning, a one, you must start at zero.

In this sense, Stüttgen posits, his friend “has no late works, only early works, because it comes from the future.” His art is immaculate and ever-renewing because it always starts from zero. At this point the Knoebels joke that VEB-Kontor, 1990/97/98, (Publicly Owned Enterprise-Office) a Masonite and mixed-media work containing 7000 palletized and plastic-wrapped boxes of the now-defunct East German laundry detergent brand IMI, advertised as “Gegen groben Schmutz” (“Against Tough Dirt”), may be testament to the artist’s search for purity.

It is possible to conceive of Knoebel’s work as beautiful manifestations of Kant’s theory of noumenon and phenomenon and the quest for the ultimately unknowable essence of things through perception. Certainly, in his fresh, searching experiments with color, shape, and volume, the artist reaches for base reality, a state of raw consciousness and perception more than any self-aware ideation. On this and all topics regarding what his work might represent, however, the artist remains silent—as usual. In the end, though, Stüttgen has identified a universal force and source of warmth in his friend’s art when he says that zero, the beginning of Knoebel’s ongoing, committed search for primal beauty, represents “the point where you wake up.” A childlike wonder at the splendors of art and a willingness to pursue them wherever they may lead him is central to the artist’s project. It inspires his ongoing “Kinderstern” (“Children’s Star”) series of paintings, which are sold through a foundation he established with Carmen to support human rights for children. And this same evergreen sense of awe galvanizes his newest works. The “Figura” series, large, rambunctious tangles of thick brown, yellow, green, and red strokes of acrylic on shaped aluminum panels, is sparked by watching his young granddaughter’s unsuccessful attempts to stay within the lines of her coloring books.

Endnotes

- Carsten Ahrens, “The Schattenräume of Imi Knoebel,” Imi Knoebel: Dass die Geschichte zusammenbleibt exh. cat. (Berlin: Kewenig, 2019), p. 51.

- Imi Knoebel quoted in Kate Connelly, “Artist Imi Knoebel: If You Want to Stay Alive You Have to Do Something Radical”, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/jul/15/artist-imi-knoebel-if-you-want-to-stay-alive-you-have-to-do-something-radical (accessed 28 February 2020).

- Johannes Stüttgen, “The Insistence on the Beginnings, the Beginning. The Core Pieces.” Imi Knoebel: Kernstücke exh. cat. (Krefeld: Kunstmuseum Krefeld, Museum Haus Esters, 2015), p. 84-85.

- Konrad Bitterli in Imi Knoebel: Linienbilder exh. cat. (Cologne: Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, 1999), pp. 33-34, translated and quoted in Imi Knoebel: Works 1966-2014 exh. cat. (Wolfsburg, Germany: Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, 2015), p. 45.

- Piene, Otto. "Otto Piene: The Development of Group Zero." The Times Literary Supplement, no. 3262, September 3, 1964, p. 812+

- Imi Knoebel quoted in Johannes Stüttgen, “I Wouldn’t Say Anything Voluntarily Anyway!”: Johannes Stüttgen in Conversation with Imi Knoebel,” Imi Knoebel: Works 1966-2014exh. cat. (Wolfsburg, Germany: Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, 2015), p. 24.