At 84, Joan Snyder Keeps Creating Bold New Work The feminist art icon presents a powerful new survey

By Devorah Lauter

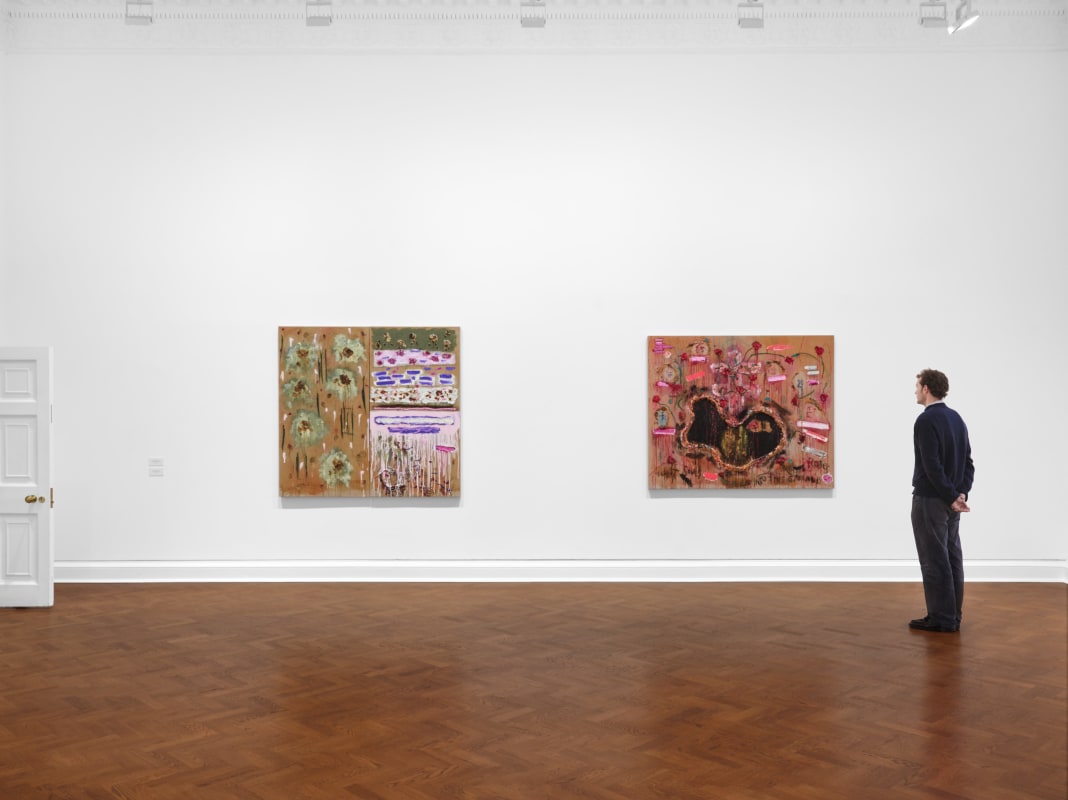

Late last month, Joan Snyder sat on the ground against the wall in Thaddaeus Ropac’s stately London gallery, her elbow leaning on a bent knee. Around her, hung eight paintings she completed within the last nine months, pulsing with the artist’s signature, expressive maximalism. They are part of her first solo exhibition with a blue-chip gallery, a survey covering 60 years in over 30 paintings. “Don’t call it a retrospective, because I still want one,” Snyder says. And boy, does she deserve one.

“Body & Soul” is on view until February 5, 2025. It proves that at 84, Snyder is making some of her best work. “No one is more surprised than I am that I keep having these ideas, and keep making these paintings,” she said. “It’s kind of magical.” The painting Roses for Souls (2024) was hanging above us. In it, a black organ or amoeba-like pond splattered with gold glitter is surrounded by floating, scratched faces. Known for incorporating other materials, fleshy, dried roses, paper mâché, and straw take shape alongside hovering, short and thick pink brush strokes. She painted it while thinking of the war in Gaza, and it is a rapturous example of her raw landscapes, which she artfully balances between careful composition and dripping, messy, unleashed freedom.

In these works, and across Snyder’s life’s practice, beauty in nature, visceral color, pain, and loss heave back and forth. Narrative qualities can be read in detail, sometimes appearing as open-book, split-down-the middle diptychs in her latest paintings, but her art has never offered a specific storyline.

As for the effort involved, Snyder, whose face is framed by a round puff of silvery, wayward curls, was more concerned about her opening later that evening. “The difficulty is going to be the gala dinner tonight,” she said. “This is easy, and you can quote me.”

Snyder is better known in the US, and relatively unknown in Europe. She first drew stateside attention for her “Stroke” paintings of the 1960’s and 1970’s, with their stacked and undulating brush marks that sometimes float on pencil-lined canvas. She also became a recognizable voice in America’s feminist, artistic movement. But the fact is, she should be a household name, equivalent to male contemporaries like Cy Twombly or Anselm Kiefer, whose artworks share certain formal qualities with hers, though their differences run deeper. Evidently, that isn’t how things went, but more on that later.

About her process, Snyder explains her recent works took longer than the “Stroke” paintings, seen in the chronological show. “When I go into the studio, it just happens,” she says. “They take a while to build up, because there are different layers I have to work on, but I easily put myself on automatic pilot. Turn up the music and go.” Before that, she also prepares with rough sketches, made in response to live music— Bach, Arvo Pärt, Requiems, Philip Glass, opera, jazz, are some favorites. “I can hear it,” she says of the way she thinks about painting. “It makes a sound to me.” Once a sketch has gestated, sometimes for years, she paints it, and something else emerges.

Always, recurring metaphors appear in layered paint and collage, like a personal, visual language. They include roses, hearts, various grids, mud, animal prints, scribbled writing, sheela na gig figures with plastic grapes hilariously stuck to the crotch, flock, and open, gaping gashes in fabric, to name a few.