A New Survey of Rarely Seen Andy Warhol Works Challenge How We Think of the Artist

Decades before the birth of social media, Andy Warhol lived his life in front of and behind a camera. Few artists of the 20th century or any century rival his fame. Warhol’s own image, that mass of platinum hair, is as iconic as his silkscreen Marilyns or Brillo Box sculptures. We all know Andy Warhol, right?

The artist’s paradoxes and prophecies are explored in Andy Warhol: Photo Factory, a captivating exhibition that opens at Fotografiska New York today. The show consists of 120 rarely seen photographs and four 16mm films. The survey of polaroids, gelatin silver prints, collages, screen tests, photobooth strips, and stitched photographs display formal innovation, thematic diversity, and startling foresight.

“When I looked at Andy,” Roy Lichtenstein, another titan of Pop Art, recalled to Jean Stein,“I looked at him as a tourist would… with wonderment. How glamorous. How strange.” The exhibition allows visitors to see Warhol as Lichtenstein did.

“When Fotografiska was closed during the pandemic,” explains Amanda Hajjar, Director of Exhibitions, “We did a small, online exhibition of Ladies and Gentlemen and *Sex Parts and Torsos”—*some of Warhol's polaroids. The swell of public interest spurred plans for a larger, in-real-life exhibition. Over a year later, Photo Factory offers brilliant insight into the artist, his time, and our own.

Warhol’s polaroids immortalize a spectacular cast of characters: rockstars, royalty, athletes, artists, socialites, and street hustlers. The enduring fame of his late subjects lends an unintentional if inevitable pathos to the exhibition. Warhol captured, in all their beauty and promise, those lost to addiction (Edie Sedgwick, Jean-Michel Basquiat), AIDS (Keith Haring, Robert Mapplethorpe), and violence (Gianni Versace and Marsha P. Johnson). Beside these tragic characters are sitters like Dolly Parton, Steven Spielberg, and Diane Von Furstenberg, whose creativity strengthened with time. The camera, for Warhol, was always neutral.

Among all this glamour, both optimistic and shadowed, Warhol captures the quotidian too. A cluster of bananas, a pile of shoes, and an unmade bed are given just as much attention as famous faces. Taking photographs was a compulsion.

“Warhol used a camera as part of his daily social interactions,” explains James R. Hedges IV, who loaned much of the work on view. “It was integral to his interactions and his art-making process.”

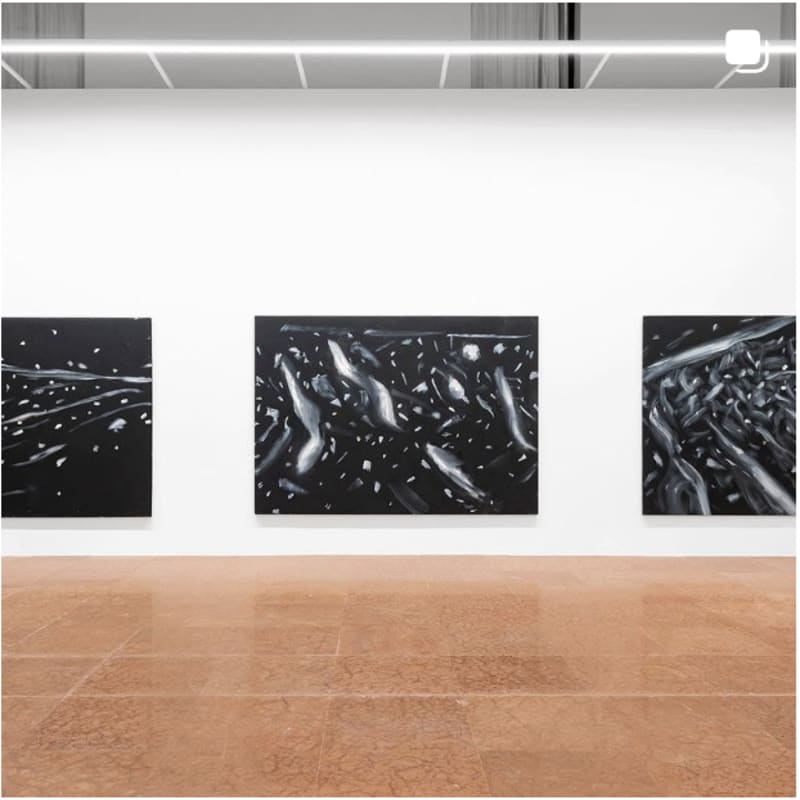

The four films included in the exhibition are all black and white, silent, and made between 1963 and 1966. What the works accomplish, despite their superficial similarity, display the scope of Warhol’s intent. Hajjar contrasts two of the films: Edie Sedgwick and Skip Stag (1965) and Lou Reed (1966). In the first, the camera lingers obsessively on the two exquisite faces, whose hypnotic beauty is broken only by the glitter of materiality: the flash of his silver watch, the twinkle of her chandelier earrings, the spark of a cigarette lighter. The result is “screen test-esque and very posed and very sexy,” saiys Hajjar. In Warhol’s study of Lou Reed, the disorienting experimentation renders the rockstar almost irrelevant. “Warhol keeps zooming in and out,” Hajjar explains. “The film is not particularly beautiful. It’s not getting the glamour out of [Reed]. But’s very Warholian: He’s doing something weird.”

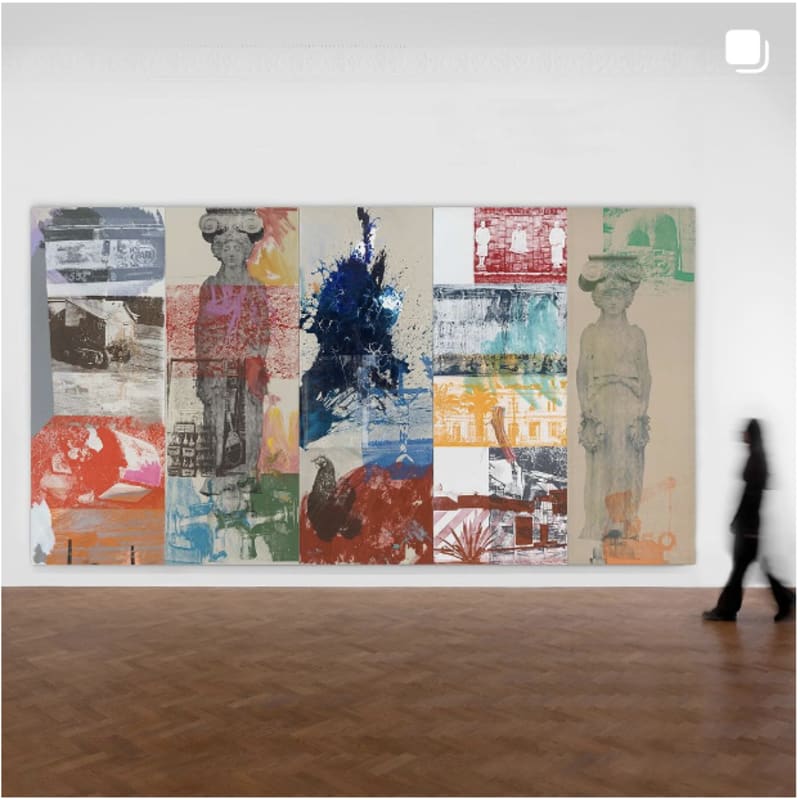

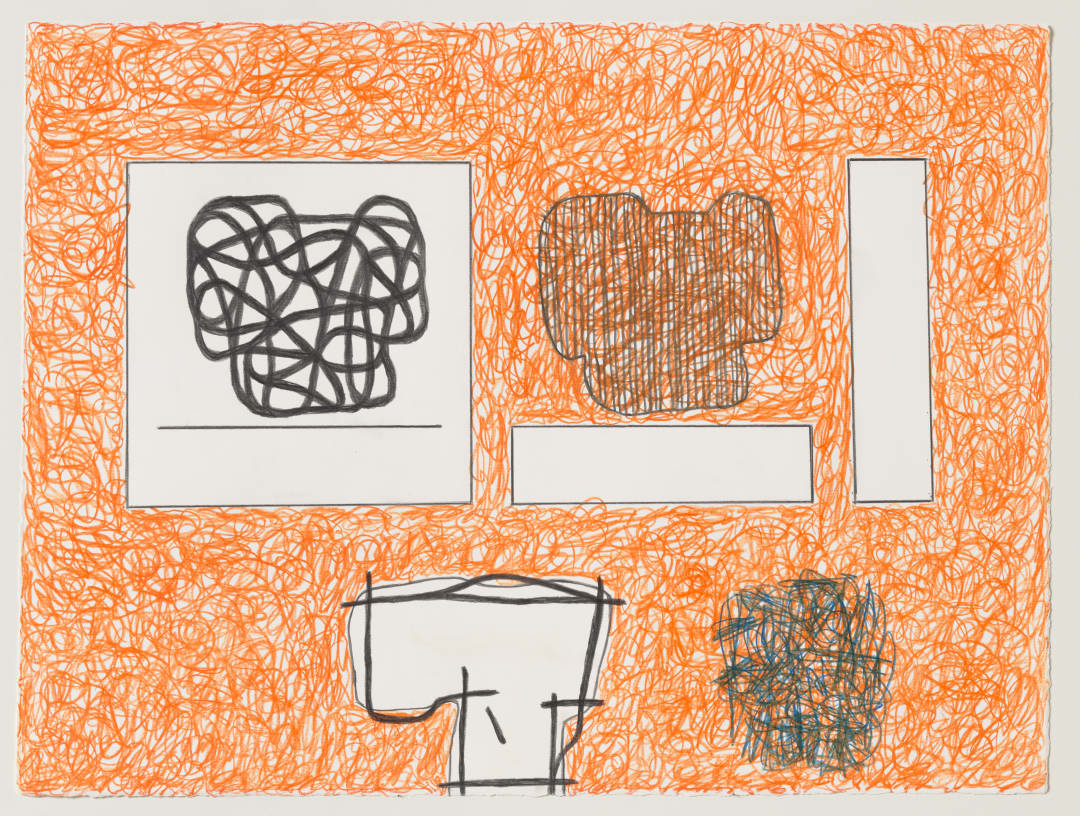

Weirdness infuses the entire exhibition. In Warhol’s stitched photographs, the final body of work exhibited before his death in 1987, the artist sewed identical images together to abstract even the most classic of artistic subjects. His collages, produced for the likes of Vogue Paris and Mondo Uomo, pull out the peculiarities inherent in fashion photography.

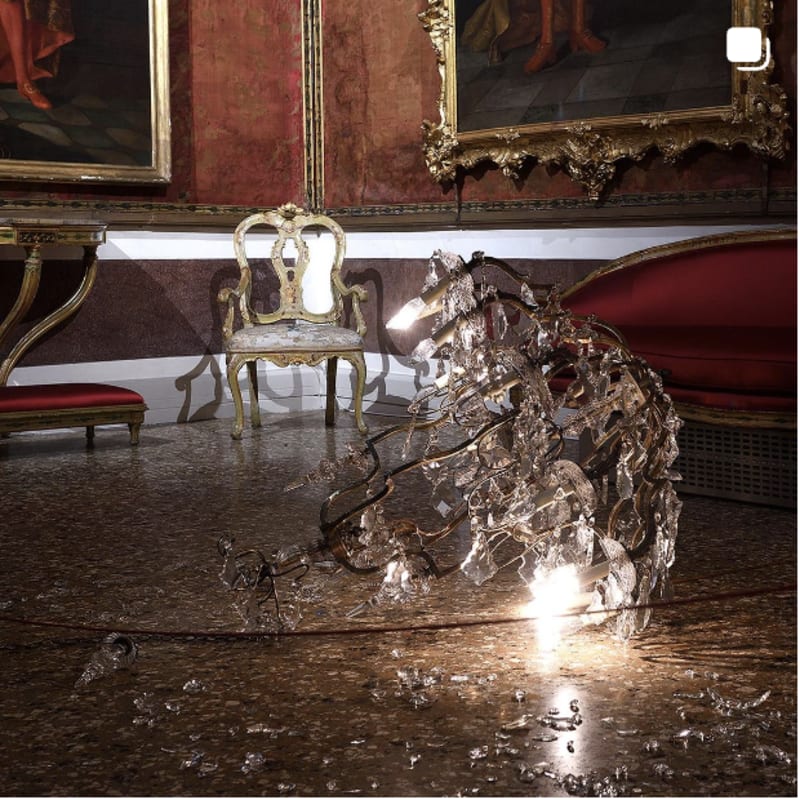

Fotografiska offers a more boisterous environment than most museums. “We don’t use a lot of white walls,” Hajjar explains. “We really encourage people to walk around with their drinks and make it a social experience.” For Photo Factory, that playful irreverence is intensified. Bright paints, aluminum foil and Warhol's own wallpaper envelop the space. Tracks inspired by Studio 54 keep the energy high.

Without a doubt, many visitors will flock to Fotografiska to share the exhibition on social media. It is easy to imagine other artists recoiling at their works becoming props for a 24 hour Instagram story, the subject of a 140 character quip, or the background for a 60 second video. Andy would have loved it.