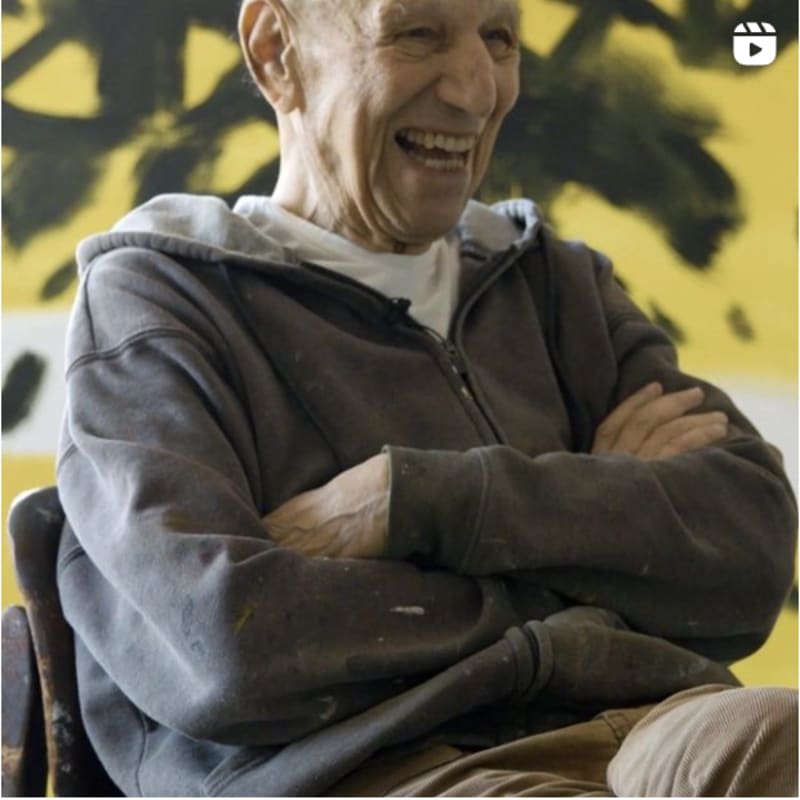

Georg Baselitz

IT’S ALL ABOUT ELKE.

Georg Baselitz recently inaugurated his show “Freitag war es schön” (“Friday was Nice”) at the Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery in Salzburg, and exhibitions at Palazzo Grimani and Fondazione Vedova in Venice. Georg Baselitz needs no introduction as he is one of the most important artists alive today.

Georg Baselitz, why this title “Freitag war es schön” (“Friday was Nice”) and what kind of exhibition do you have at the Ropac Gallery in Salzburg?

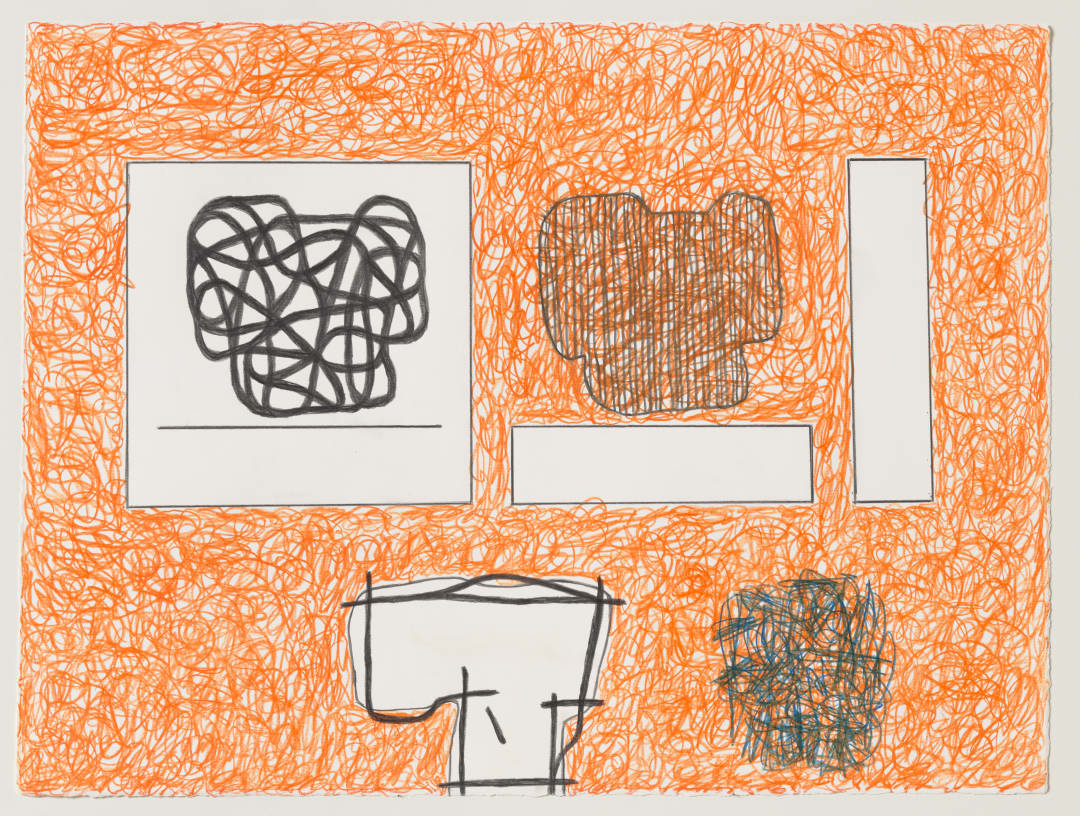

Playing around with titles is part of my oeuvre since many years. “Freitag war es schön” is the title of the exhibition in Salzburg. Most of the paintings in Salzburg have similar titles and are inspired by Fontana. On the one hand I am thinking of Fontana and on the other of Emilio Vedova, who was my friend. I am always in between those two, and I have to protect Vedova from Fontana.

Sadly Vedova died in 2006 and is buried in the Cimitero di San Michele in Venice. How come you were such good friends?

Actually it was almost impossible to be a good friend with Vedova because he was very eccentric and complicated. I can’t really explain our friendship. Maybe it was because we had a similar physiognomy. We were both tall and had a beard.

Your works on show in Salzburg and Venice are very colorful. Is your use of strong colors an homage to Roy Lichtenstein, and why is such a different artist as Lichtenstein of interest for you?

Until the age of maybe 60 I thought that to protect what you are doing by yourself you have to discriminate against all the other artists. For example, Lichtenstein, Rauschenberg, Fontana. I thought you just had to fight against those artists, and that’s what I did. But in the last 20 years I have changed my mind. My paintings became so singular, so typical of me and my own way of painting, that I can have those ideas of Picasso, Fontana and Lichtenstein and all the others within my work. Similarly I can be inspired by Asian art, although those artists are anonymous.

Why were you an admirer of Jackson Pollock and Clyfford Still, and later Tracey Emin?

Everything at its time. I was 20 years old in 1958 when I saw the big Pollock retrospective at the art school in Berlin, and the exhibition of American expressionist artists. The impact on me of the works in those exhibitions was so strong that I said, “I cannot jump on this train. This is not me.” I had to find something completely different from what I saw there, and I had the idea for those very first paintings of mine which became a scandal in Berlin and caused a public prosecution. My professor at that school was an activist and a contemporary modern painter, and when he saw my paintings in answer to the American artists he said, “This is anachronistic. This time is over.” The effect on me of his comment was that I went on doing what I did, maintaining this anachronistic gesture.

Georg Baselitz, the School of London painters like Auerbach and Freud were also not abstract artists. Do you consider them German painters, even though they were in London?

Yes. My first impression of the London School was that they were old fashioned, whereas my colleagues and I followed the idea of going forward into the future. I knew Lucian Freud and we had a bit of a fight because we had the same gallery in London and Freud didn’t like it at all that I had an exhibition there. This was in the 80s when I had my first exhibitions in London. At a certain point I wanted to explain to myself why those artists of the London School – who I knew and considered extremely conservative, even more than conservative – had this special kind of outsider position. It occurred to me that Freud and others from the London School had a 20 years gap in their biography, owing to the fact that they had to flee Germany when they were small because of the Holocaust. It is a crack in their education, and they just started to paint what they knew from home. I went up against the London School in a fight about what was called contemporary art at the time and the question was: Who will win?

Germany is a country that during the Nazi regime banned German Expressionism and you wanted to avenge this in your work. Do you still have this strong reaction vis a vis Germany?

The stronger impact on my work was not Nazi art and the fact that the Nazis forbad the Expressionists. The stronger impact on my work was the one that I felt in my own life; how the communists dealt with socialist realism, and the fact that everything else was not allowed under the communist regime.

In the late 60s, after you were first in contact with the art movement of the Mannerists in Florence in 1965, you made a complete innovation and decided to put your paintings upside down. Was it the inspiration of Pontormo, Rosso Fiorontino and others that decided you to invert your paintings as your signature?

No. It was totally independent. Upside down painting had nothing to do with the Mannerists. When I was a young student I read a book about the Mannerists, and after this I went to Florence because I wanted to find the original sources from this book. And the other point was that I suddenly realised that I was not an idiot, as I thought of myself before, and that I could reflect my own position as I was becoming an intellectual. As a result I went even further away from what was called contemporary art. I went backwards; and further backwards.

Why did you decide to do paintings upside down and then keep on doing them?

There was a big criticism of everything I did until this point of time, because I did not fit into the mainstream and into “contemporary art”. All my colleagues like Richter, Polke, Palermo, all those famous Germans, thought that I was an idiot. And I thought that they were colonialized by the Americans, because they did what the Americans taught them to do, and the French. Only recently I realized that the first one who was completely independent and singular as a German artist was Joseph Beuys. Beuys played tricks and games with Wagner and German mythological stories, and I find it very interesting.

But you haven’t explained why the upside down.

We’re getting there. Painting in comparison with the real world is bullshit. It’s crap, it’s socialism. The alternative was to paint abstract, but that was not my way; the Americans and others already did it. So I thought I’d go back. I’m very naive, very direct, and extremely intellectual. I know better than my teachers and everything that was painted so far. I just put it upside down, and when I did the first painting this way it was a complete liberation for me and I wanted to influence all the others. I said, “Friends. I found the solution. Let’s do this. You should do the same.” Everybody thought I was crazy.

Did you paint them normally and then turn them upside down?

I had to prove to everybody that I was a really good artist, that I could paint, and the proof was made by the fact that I really painted them upside down. I took a photograph and put it upside down and just painted. I no longer had to compare the painting with the real world. I did not have to prove that the portrait was right or that the landscape was right. Suddenly, everything was just about painting.

Georg Baselitz, in your paintings you emphasized certain human body parts and made them very big. Why did you have this idea?

I have painted feet and hands continuously since 1963, but the methods which I have used to do those paintings over time are completely different. My strange addiction to hands and feet and noses is because of trying to find a solution to the problem that I feel extremely uncomfortable about the Christian church and religion. It’s a psychological, unpleasant feeling of fear, and even though my uncle was a priest and helped me a lot, the fear remained. My own theory as to why is based on the romantic idea that people living north of the Alps do not believe in angels, have different religious traditions to those to the south and are historically not Christians. I believe more in trolls, elves, and gnomes than in angels.

But what about your emphasis on nose and foot?

Feet are the contact with the ground. They are manipulated on reception from the earth. The receptor towards God is missing, it’s all towards the earth where the gnomes and the elves come from. And in most portraits the nose is approximately in the centre of the painting and there’s usually a lot of expression in the nose. My inspiration to paint noses is from Ferdinand von Rayski, who in the 19th century painted his own nose, drunk, in the middle of the painting. A big red nose. This was the beginning of my so-called Rayski portraits. It was Tachisme, with the nose in the middle.

Sir Norman Rosenthal once asked you if you are religious and you said, “Obviously not.” Why do you say that art is the most interesting thing there is, and not religion?

My whole life I am trying not to be colonialized. Whenever I painted a painting the first thing that came towards me was censorship, and that censorship is mostly based on moral ideas, which, again, are based on religion. This was the case with the allegedly pornographic penis painting and the upside down paintings.

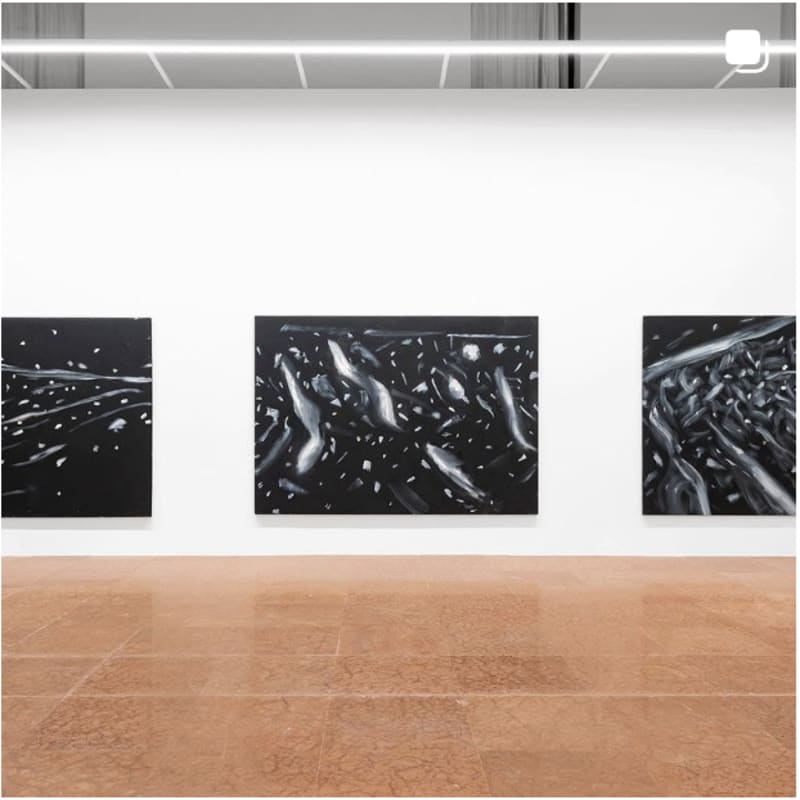

What is this exhibition at Ropac, “Freitag war es schön”?

It’s Elke, after a photo from the late sixties.

Is your wife Elke the aim of this exhibition?

That’s not a question that I can answer. Elke is my huge muse. I have painted her for 62 years. There was an exhibition at the museum in Fort Worth, Texas, which was dedicated to Elke. Maybe one day people will write books about myself and Elke. The variety of Elke paintings is like a fil rouge running through my career, parallel to anything else I have invented. I went there from the very beginning and it has never ended, and it doesn’t end here in Salzburg because I cannot stop doing it. The exhibition at Fondazione Vedova in Venice is also all about Elke, and you will find portraits of Elke at Palazzo Grimani too. But I never repeat myself doing Elke. I found this image and reinvented it again and again over 60 years. Between Salzburg, Grimani and Vedova, you will see me reinventing Elke within the last two and a half years, and all three exhibitions are totally different. How they are done and the appearance is completely different every time. I am not Auerbach!

Why are you so obsessed by painting Elke?

What else should I do?

Is it an act of love?

Actually I am always looking to the inside, to the inside of my life and my brain and what’s going on up there. I was not an artist who went outside into the landscape to find a motive. On my brain was where I grew up, what I saw when I was a child, and what I had around me. It’s the landscape from my childhood. It’s my wife from early days. And it’s the still life that I had in my mind from a very early time. I am in a hermetic world. That’s where my inspiration comes from, and Elke is part of this. When I went to Italy for the first time as a young student, I did not start painting the landscape of Italy. I sent a letter to my brother asking him to send me a picture of the apple tree from the village where I grew up. This was what I wanted to paint when I was in Italy for the first time.

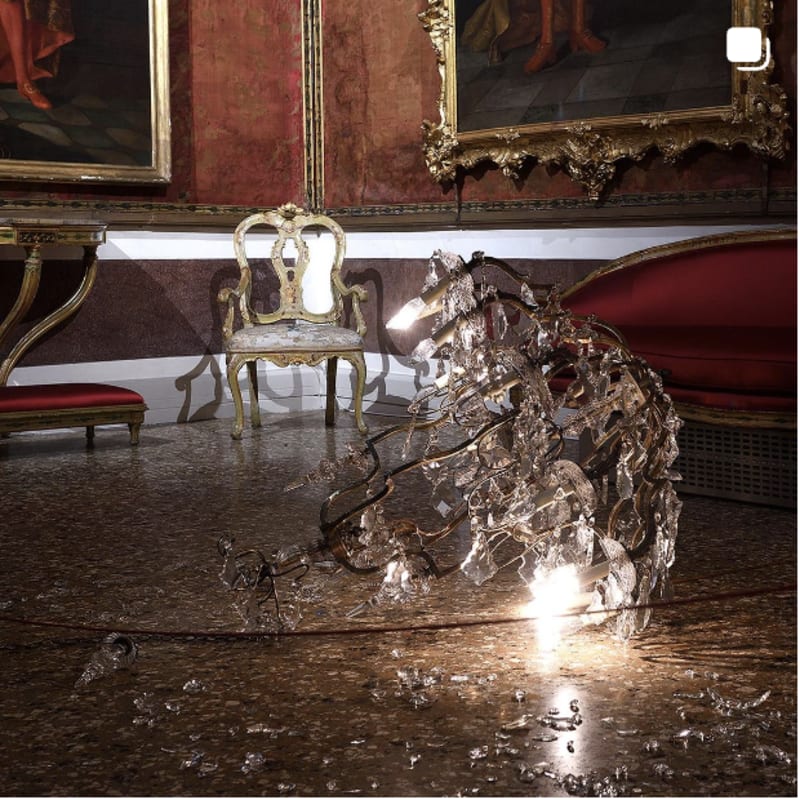

Georg Baselitz, you seem to have a special link with Italy, in particular with Venice. You had a major exhibition at the Accademia during the Biennale of 2019, and now you are making a long term loan to the Palazzo Grimani and also showing an exhibition for the Vedova Foundation. What is your special link to Venice?

I do have a special relationship to Italy. On the one hand I would call the Biennale in Venice in 1980 a catastrophe. There was a press conference and Josef Beuys was the big star at that time, so everybody listened to what he said and hundreds of journalists followed Josef Beuys into the German Pavilion. Anselm Kiefer and I were standing on the side like little schoolboys, and Josef Beuys’ statement on the art that he saw at the Pavilion, of my sculpture, was that it didn’t even have the quality of the first semester. German TV showed the German Pavilion with my sculpture, and the background music they used was a famous German Nazi march called Horst-Wessel-Lied. It’s the worst song that you could possibly have as the background music for a piece of my art. This was actually the point where I started my big skepticism towards society and everybody around me. You have to understand: I had this sculpture in the German Pavilion, which had a gesture with a hand with an arm in the air. The German interpretation of the sculpture was that it was a Nazi salute, which was totally not true, it was impressed by an African Lobi figure. But the reception in Germany was that Baselitz and Anselm Kiefer did a Nazi sculpture and a Nazi artwork in the German Pavilion, which additionally was built by Nazis and has Nazi architecture. So this was the German reception of my first appearance at the Venice Biennale. On the other hand, at the same time I received an invitation from Xavier Fourcade and Ileana Sonnabend to come to New York. I had an exhibition at both galleries which became my international breakthrough. This is how Venice and Italy became extremely important to me and still is.

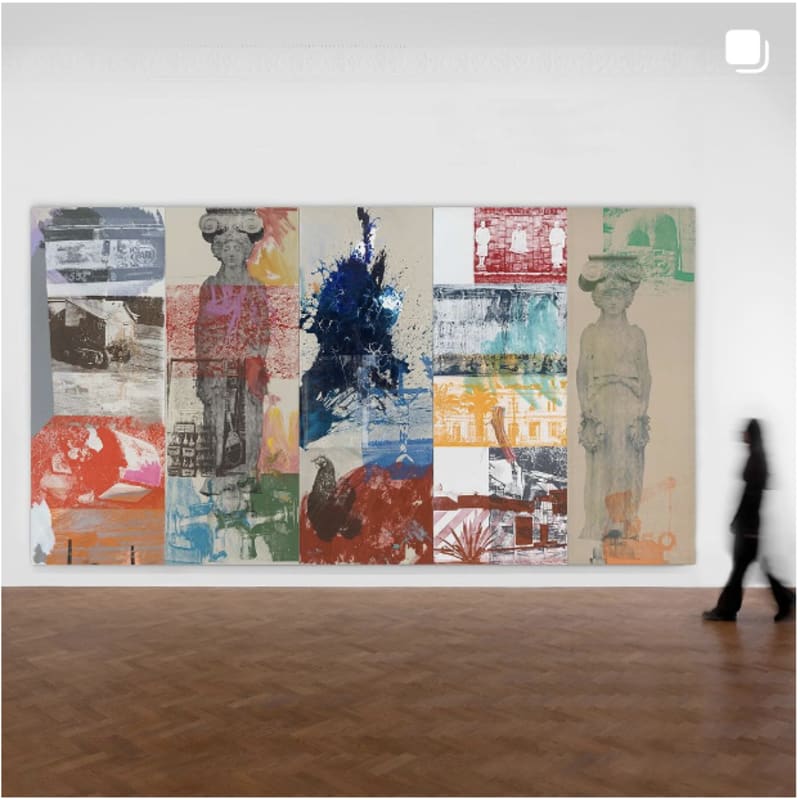

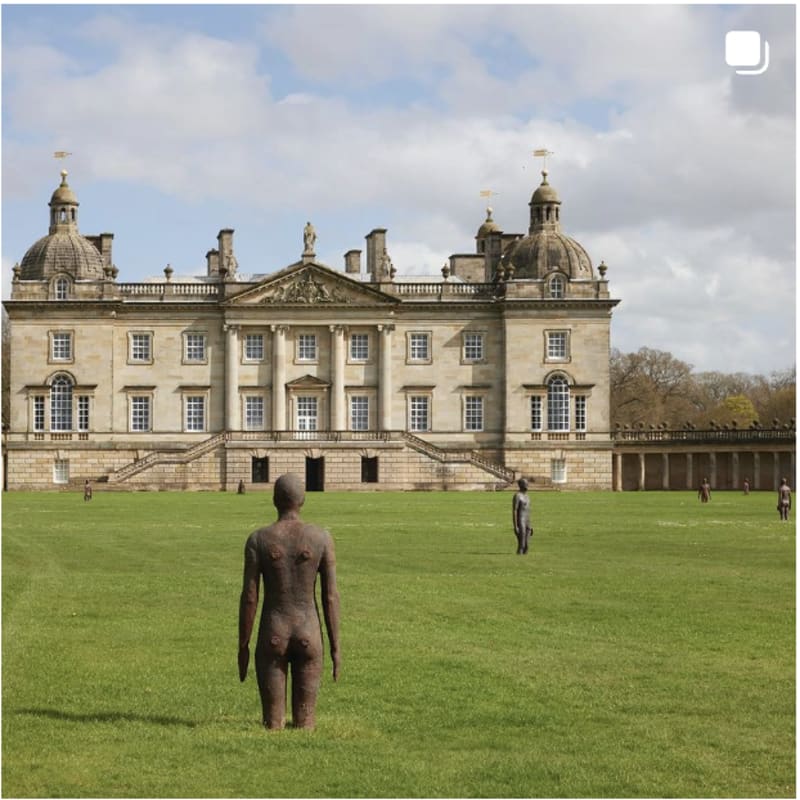

You are replacing twelve lost family portraits in the Palazzo Grimani with your own paintings, which you have made available to the museum on loan for several years. How does it feel to be part of the historical tradition and in succession of the old masters?

One should not forget that Venice has become one of the world’s most important venues for contemporary art due to its prestigious position in art-history, but also because of the Biennale. There is probably no place in the world that offers a stronger contrast between past and present. And I find a palace like Palazzo Grimani, like palaces in general because of their immobility, the most interesting thing about visible culture that I can think of. It is of course a loss that the original content is absent at the Grimani, but we can imagine how it used to look. I always associate Grimani with Casanova. His father was unknown to him, but his mother was an actress in Venice. The Grimanis had a theatre there and Grimani supported Casanova financially. Maybe there is something to this story … It is definitely something very unusual to see my new paintings in this palace in Venice and to know that they will stay there for several years.

And what do you feel about Imperia in Italy, where you also have a house?

There it is always fantastic. Nobody’s interested in me and what I am doing. They call me Maestro and everything is fine.

In 1963, almost 60 years ago, you did your first exhibition in Berlin, at Werner and Katz’s Gallery. Have the conditions of being a German artist changed?

The conditions since then for artists became extremely bad. The situation in Germany and German museums is disastrous for artists. There is no money, there are no visitors, there is low interest in contemporary art and art overall in Germany compared to other countries. But now I also have an Austrian passport, and I live and work in Austria as well as Germany and Italy.

Do you feel that you are in exile from your own country?

Not as much and as strongly as in Italy, because in Austria I can read the newspapers!

In his autobiography “The World of Yesterday” the writer Stefan Zweig describes what happened to him in Salzburg. How is it for you?

Even worse. I moved to a village close to Salzburg, where the composer Schoenberg used to have a holiday place, and he was rejected. After I moved there I came across this book about the history of this village and found out that they were already extremely anti-Semitic in the 1920s. Already in the 1920s the newspapers wrote articles that this little village where I have my place now should be “Judenfrei”.

How did you cross this strange and difficult year of pandemia?

I have worked like crazy. More than ever before. I hate the time. I think it’s crazy. I don’t like what I call the dictatorship. I don’t like politicians telling me what to do and what not to do. I was always in opposition to their mindset. Nothing has changed.

We have the corona virus but somehow you are able to have exhibitions in Salzburg and Venice, and a huge retrospective at Centre Pompidou in Paris in October.

Although there is this bad situation right now which has happened to me in different ways already many times before, I try to escape the madness and leave this hysteria to others. I stay true to myself.