Erwin Wurm 'Surrogates' Exhibition review

By Meara Sharma

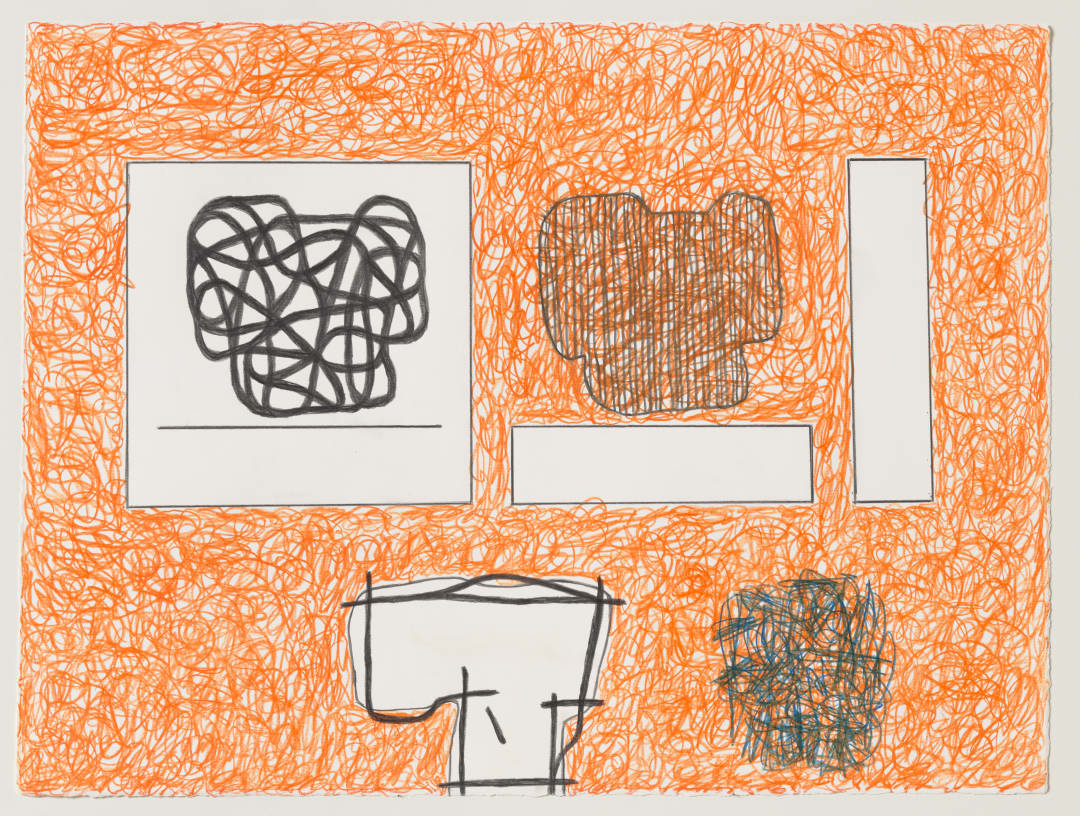

Empty suits, a thought bubble with legs, and an inflated vaginal high-heeled shoe: The new sculptures in Erwin Wurm’s exhibition “Surrogates” circled themes that have preoccupied the Austrian artist since the 1970s, from the absurdity of everyday life to the permeable membrane between humans and objects. Throughout the gallery, garments from Wurm’s “Substitutes” series, 2022–, stood erect, floating on the shapes of absent figures, as if worn by invisible people. From afar, the works seemed soft and insubstantial, like clothes on a hanger, but closer up they revealed themselves as solid forms made of painted aluminum, with a scale and heft that winked at classical sculpture. An enormous pair of white trousers with a pink sweater appeared buffeted by the wind like a scarecrow—something familiar bent into the uncanny. A child-size outfit conjured up a bedroom decoy for a midnight escape. Tall, recurring monochromatic suits—many caught mid-stride—might have been businessmen in corporate armor, their bodies as well as minds co-opted by their employers. “Clothes are our second skin,” as Wurm has said, and those skins are inevitably linked to economics, status, and identity; sometimes, their power and subjectivity can even subsume us.

If “Substitutes” evokes this idea through the erasure of the body, Wurm’s 2024 “Paradise” sculptures do the opposite. A pair of hyper-enlarged, sideways stilettos made of steel, resin, and Styrofoam—one sinewy and smooth, the other knobby and bulging—abstract the form of the shoe and insinuate fleshy limbs and intimate recesses. Elsewhere, Wurm’s “Mind Bubbles,” 2024, oblong lumps of bronze sitting atop ostrich-esque legs, provide a cartoonish metaphor for losing one’s mind. More inspired is the “Dreamer” series, 2024: dainty limbs engulfed by voluminous pillows (ostensibly squishy but actually made of cast aluminum), evoking the depths of the unconscious on the one hand and a pulpy horror-movie murder on the other.

Such dualities run through Wurm’s oeuvre—he’ll muse on mass production while employing the technologies that fuel it, or use a raunchy slapstick joke to launch an earnest critique of capitalism. His recent artworks suggest feelings of ambivalence, even nihilism. Early in his career, Wurm might have used found objects and secondhand clothes as sculptural material out of financial necessity. Now he’s part of the machine, and in probing our relationship with the material world he’s created an exaggerated version of it, full of more things: heavy, bulky, shiny, reproducible toys.

Wurm’s participatory “One Minute Sculptures,” 1996–, then, seem to be a kind of ephemeral antidote to commodification, both for himself and the viewer. This series invites visitors to engage with assorted props and briefly become sculptures themselves. In the upstairs room of the gallery, I hesitatingly followed Wurm’s instructions to place a police hat on my head (Be The Police, 2024) and press the heels of a pair of shoes into a sculptural form that resembled a shaggy pile of white clay (Neurosis, 2020–23). I felt like I was performing a vaguely suggestive one-woman show for the gallery attendant who, noticing me falter a bit, gently demonstrated how to bend over and balance a broomstick between my forehead and a sort of craggy pedestal (Obey, 2024) and don a curved wooden chair like a constricting backpack while standing, strangely exposed, on a plinth for one minute (The Idiot, 2024). The experience of enacting the sculptures was uncomfortable, silly, erotic, fleeting, and surprisingly poignant: in sum, extremely human, especially in contrast to the looming, oversize garment figures beside me, devoid of bodies—quite literally soulless—which would be at home as advertisements for a fashion label. On my way out, enlivened by the hint of BDSM, I barely noticed a sculpture of a life-size blue blazer and trousers, frozen amid a throng of art students. Once the students cleared, the piece (Ghost, 2022) remained there, lingering like a skeptical guest, unsure of whether to take a step further, or whether it wanted to be there at all.